|

|

|

|

The weekly newsletter of the México Solidarity Project |

|

|

|

December 8, 2021/ This week's issue/ Meizhu Lui, for the editorial team |

|

|

Bang Bang, You’re Dead! |

|

As a child, the first person I ever knew personally who died turned out to be my piano teacher’s daughter, shot by her brother over a squabble about what TV show to watch. The second: a sixth-grade classmate shot dead in a hunting accident.

Years later, I didn’t want my little son to have any toy guns. But you can’t escape the gun culture in the United States. Kids ingest it with their pablum. Yosemite Sam. GI Joe. Even without a toy gun, my son could still point his tiny finger and announce, “Bang bang!”

Guns infuse our national DNA — and have right from the start. With guns, settlers from Europe could clear the land of the people already here. With guns, our government today still insists, we can solve social problems. We export that notion worldwide. We export actual guns as well. Our coddled gun companies find exporting death highly profitable.

In México, as our Voices interview makes clear this week, that death has become a constant. Some 70 percent of the traceable guns that figure in Mexican murders come from the United States. The Mexican border doesn’t deter foreign capital, drugs, or guns. It does stop migrants trying to flee from the combination of those three toxic ingredients.

Meanwhile, the little “pretend gun” fingers grow into bigger fingers that pull real triggers. Bang bang, you’re dead! Bang bang, I’m dead. Bang bang.

An editor’s note: We have some changes in our México Solidarity Bulletin format this week. We’re going to be featuring some original political commentary from insightful activists and analysts on both sides of the border. Our México Solidarity Project’s own Bill Gallegos gets us started. Check out his column in our Reflections section below! |

|

|

|

Don’t miss an issue. Subscribe to the weekly México Solidarity Bulletin! |

|

|

|

|

Back in the 1980s, accompanying — and getting to know — courageous activists risking their lives to gain justice in Guatemala, El Salvador, and Colombia changed the course of John Lindsay-Poland’s life. He’s dedicated himself ever since to working to free all people from the fear of violence. Lindsay-Poland is currently working on research that connects militarization and human rights abuses and organizing to demilitarize US policy in Latin America. He coordinates the Stop US Arms to México campaign, a project of Global Exchange. |

|

|

When did the era of gun violence in México begin — and why?

John Lindsay-Poland: Between 2004 and 2010, a toxic cocktail of issues changed the pattern of gun violence in México. First, market dynamics shifted. The international narcotics business had been centered in the Andes, but the drug wars there shoved much of that industry — including synthetic drug production — to México.

Second, beginning in 2007, Presidents Calderon and Bush jointly declared a “War on Drugs,” using military strategies to stop drug trafficking. Third, since the drug trade is illegal, the only way to resolve disputes is through violence. And lastly, in 2004, the ban on assault weapons in the US expired. The subsequent sales and trafficking to México of ever more deadly weapons led to an internal arms race between cartels competing for territory — and between the cartels and government forces.

What strategy did the “War on Drugs,” officially the Mérida Initiative, follow? |

|

The War on Drugs initially followed a military and police strategy aimed at taking out the drug kingpins through massive US support. That backfired, because taking out the head of a cartel triggered violent competition between the factions wanting to take the kingpin’s place and because so many government forces were colluding with criminal organizations. |

|

The Mérida Initiative, since 2008, has weighed in at $3.3 billion. Last month the US and México put this Initiative to bed, with both nations agreeing that it had been a failure. Will this end to Mérida mean a reduction in the arms flowing into México?

No. The Mérida aid money, already by 2010, had begun to shift away from a military strategy. But Mérida was never about giving México firearms anyway. The support came more in the form of surveillance assistance, training, helicopters, and other equipment.

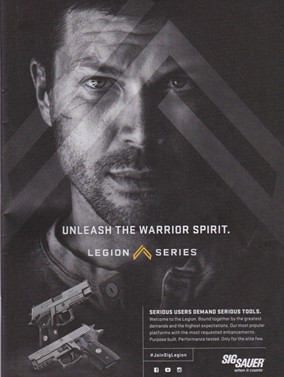

Now, Mérida and assistance with military gear are not so much the problem. It’s arms sales. Mérida money went through the State Department. But Pentagon assistance doesn’t require congressional review and continues to be significant. We also have private commercial sales. The gun manufacturer Sig Sauer has a $5.5-million license to sell automatic rifles to the Mexican navy, a program currently put on hold by Congress.

US weapons from all these various sources have turned up in many extrajudicial killings, including the disappearance — by government forces — of 43 rural teachers college students at Ayotzinapa in 2014. The truth is, when guns go to México, we don’t know who the end users will be, whose fingers will pull the trigger. |

|

Do you see improvements since AMLO became president?

It’s discouraging. AMLO has given unprecedented authority to the military. He’s put the military in control of ports and construction projects. He created a new National Guard focused on migrant control, with soldiers who carry Sig Sauer semi-automatic weapons. A single institution — the army — now has authority in Mexico over most everything gun-related, from arms manufacture and gun imports to confiscated weapons and sales to police and private entities. The army even controls the gun registry, with no civilian oversight to any of this. |

|

|

We’ve also seen almost no progress on serious human rights cases involving the military, most notably the forced disappearances in Ayotzinapa and Nuevo Laredo.

That said, we do see an encouraging development. In August 2021, México’s Foreign Relations Ministry filed suit in a Boston court against eleven US gun manufacturers for their role in gun proliferation. It’s easy to buy U.S. guns in states like Texas and Arizona, and it’s not hard to transport them illegally into México. The suit seeks to reform how gun companies market their products, how they, for example, hype the military qualities of their guns in sales to retail markets.

México also is asking for damages over the horrendous number of unnecessary deaths. Within the US, laws prevent victims of, say, a tragedy like Sandy Hook from suing the gun manufacturers involved. México is arguing that crimes committed in Mexican territory don’t fall under those laws.

This Mexican position represents a breakthrough. For once, government officials are putting forward a solution that doesn’t focus on border security! We know all too well that the vast majority of drugs and guns won’t be stopped once they make it to the border.

What’s helping your organization — as your name puts it — “Stop US Arms to Mexico”?

México’s lawsuit is bringing new attention to the role of gun companies in both the US and México. And another Mexican initiative — #PazSinArmas, Peace without Arms — is bringing together a dynamic new coalition of people from various sectors, including activists working on gender violence, human rights, and migration. In the US Congress, interest in controlling gun exports to México is growing.

Everyone fighting for gun violence prevention in the United States needs to know that guns made or sold in the US are leading to more gun homicides in México than in the US itself. Solidarity across borders isn’t just possible, it’s essential to end the scourge of gun violence that’s plaguing us all. |

|

|

|

The veteran Los Angeles-based activist Bill Gallegos has been howling at the moon ever since he emerged as a Chicano liberation leader and revolutionary socialist a half-century ago. A deeply committed environmentalist, Bill has plenty these days to howl about.

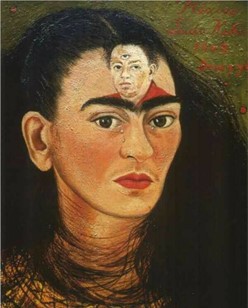

Frida y Yo

The news literally made me ill when I heard it. Early last month, the Argentine billionaire Eduardo Constantini shelled out $34.9 million for Diego y Yo, an iconic self-portrait of the revolutionary Mexican artist Frida Kahlo. |

|

I do not use “revolutionary” lightly. Frida became a member of the Mexican Communist Party in the 1920s and remained a staunch anti-imperialist all of her life. That history made the sick irony of seeing her art consumed as the latest bauble in a billionaire art collection all the more disgusting, another sad sign of a decaying capitalism that transforms everything it can into lifeless commodities. |

|

Constantini’s mega-million purchase shouldn’t surprise us. Profiteers have had their eyes on Frida for some time. We’ve become used to seeing her image — and her art — appear in an endless stream of commercials for everything from Converse and Zara to the Bank of America and Samsung. And, most recently, only a lawsuit prevented Mattel from producing a “Frida” Barbie doll!

Most people still don’t know that Frida dedicated her life and art to creating a truly free and independent México, to honoring that nation’s working class and campesinos. Her work reflects a deep respect for México’s Indigenous roots, a stance that immediately placed her at odds with the Eurocentric influence on many Mexican artists. |

|

|

Frida’s indigenismo asserted both her pride in being Mexicana and a challenge to the Yanqui imperialism that had robbed México of its northern territories and endeavored to impose its cultural values on the Mexican people, artists included.

That stance made Frida Kahlo a fierce inspiration to thousands of artists throughout Mexico and América Latina. She also inspired generations of Chicana artists in the United States. They saw in Frida a woman unafraid to acknowledge her pain, her vulnerability, and her rage. She depicted all these sides of herself in her art, especially in her myriad self-portraits that captured not only the experience of having had polio as a child and suffering horrible injuries later in life, but also the patriarchy of Diego Rivera, her longtime lover and a serial mujeriego.

As a young Chicano activist in the 1970s, the works of Kahlo, Rivera, Siqueiros, and other Mexican artists had a powerful influence on my political development and my lifelong devotion to the freedom and self-determination of the Chican@ people. My admiration for Frida had absolutely nothing to do with the commercial value of her works. So maybe then you can understand why I went totalmente asco when I heard that some gachupin billionaire now has his grasping hands on Diego y Yo. |

|

|

Recent news reports and commentaries, from progressive and mainstream media,

Leila Miller, México’s leader puts job on line, Los Angeles Times. Why the president is trying to give voters a chance to kick him out of office early.

Mexico agrees 22% minimum wage hike in 2022, industry groups say, Reuters. The Mexican government’s National Minimum Wage Commission is advancing another step to combat the country’s vast wealth disparity.

Meagan Day, How the Mexican Revolution Made John Reed a Red, Jacobin. John Reed’s thrilling dispatches from the front lines of the Mexican Revolution could have made him a pop culture celebrity. Instead, the experience made him a committed socialist.

Étienne von Bertrab, La disputa por el sistema eléctrico mexicano, Jacobin América Latina. Con la propuesta de reforma constitucional que el presidente envió al Congreso el pasado 30 de septiembre se abrió una batalla decisiva para el gobierno de la Cuarta Transformación.

MPP will be reinstated, Border/Lines. US and Mexican authorities are restarting Remain in Mexico, also known as the Migrant Protection Protocols, in a limited fashion, even as the the Biden administration lays the groundwork for the program to be terminated again.

Fabiola Sánchez, México president reaches midterm with high approval rating, Washington Post. About two-thirds of Mexicans approve of the job he is doing.

Ulises Rodríguez López, AMLO ya es el presidente con mayor aprobación en todo el mundo, Polemón. AMLO tiene 69% de aprobación, lo que lo ubica más de quince puntos porcentuales por encima de Angela Merkel de Alemania. |

|

|

The Mexico Solidarity Project brings together activists from various socialist and left organizations and individuals committed to worker and global justice who see the 2018 election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as president of México as a watershed moment. AMLO and his progressive Morena party aim to end generations of corruption, impoverishment, and subservience to US interests. Our Project supports not just Morena, but all Mexicans struggling for basic rights, and opposes US efforts to undermine organizing and México’s national sovereignty.

Editorial committee: Meizhu Lui, Bruce Hobson, Bill Gallegos, Sam Pizzigati, Courtney Childs, Victoria Hamlin. We welcome your feedback. Interested in getting involved? Drop us an email! |

|

|

|

Web page and application support for the México Solidarity Project from NOVA Web Development, a democratically run, worker-owned and operated cooperative focused on developing free software tools for progressive organizations. |