|

|

|

|

The weekly newsletter of the México Solidarity Project |

|

|

|

December 1, 2021/ This week's issue/ Meizhu Lui, for the editorial team |

|

|

Coming Down from the Ivory Tower |

|

“Ivory tower” has become the phrase we use to describe a place cut off from the rest of society, where a select few ponder questions disconnected from the practical concerns of everyday life. The “ivory tower” tag most typically refers to colleges and universities, and these institutions certainly do precious little to connect with common folk. They connect with power. What they ponder and teach reflects the interests of those who rule — and regularly undermines the well-being of people outside their ivory tower walls. Most academics in the United States and México seldom give much thought to this power connection. They assume that Europe’s classic economic and cultural models should run the world, and their teaching and research serve to impose these models on everybody else. Some academics, fortunately, see the world in different terms. They believe that real education begins with recognizing the contributions — and intellects — of everyone, including those currently at the bottom of our social ladder whose ancestors built the great civilizations of Mesoamerica that barbarians from Europe so relentlessly destroyed. Count Javier Bravo, our Voices spotlight this week, as one of these more thoughtful academics. He believes that education, the foundation of all society, can never be as neutral and disconnected from everyday reality as our ivory tower imaging implies. The conflicts currently roiling education — everything from teacher strikes to arguments about elitism — boil down to questions about who really matters. The research papers and policy proposals our ivory tower drops down upon us rarely address these questions. Maybe we need some good old adobe mud to help us build school systems that answer the most basic question of all: How do we construct societies that provide everyone a good life? |

|

|

|

Don’t miss an issue. Subscribe to the weekly México Solidarity Bulletin! |

|

|

|

|

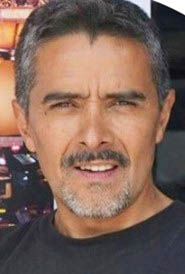

Javier Bravo, a co-founder of the México Solidarity Project, teaches at the University of Guanajuato, where he belongs to the university’s faculty union. Bravo has been in close contact with auto workers at the nearby GM plant who have rejected a management-friendly charro union contract. He’s currently working to build solidarity between those workers and the US labor movement. An activist in Morena’s left, Bravo’s advocacy sees political education as the key to social transformation.

When did México start universal public education?

The Constitution of 1917 promised education, provided by the state, to every Mexican. Under President Cárdenas in the 1930s and into the 1950s, this universal education became actually socialist in content. |

|

|

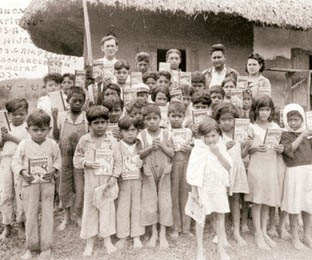

The educational system sent teachers out to bring indigenous and rural communities into the 20th century, and many of these teachers became advocates and organizers for the people they lived among. They grew to understand and respect these people. |

|

Graduates in both medical and teachers schools did two years of service in under-served areas. In fact, that’s still the rule.

Did the unions of these activist teachers also promote social justice?

The Sindicato Nacional de Trabajadores de la Educación, the SNTE, formed in 1949, but the union became more and more corrupt as the ruling PRI party — after the Cárdenas years — become more and more conservative. |

|

|

In 1979, teachers in the poorer rural states founded a breakaway union, the Coordinadora Nacional de Trabajadores de la Educación, the CNTE. These CNTE teachers maintained the earlier radical traditions. Beginning in 2013, they organized massive protests against the neoliberal education reforms under President Peña Nieto.

Nieto’s reforms mimicked the US model and linked teachers’ jobs to how well their students performed on standardized tests. The tests didn’t fit the needs of students and turned teachers into widgets. And the Eurocentric content of this approach to schooling demeaned indigenous peoples. Between 2013 and 2018, the government fired thousands of teachers. Others were injured and killed in clashes with government forces.

The CNTE today is still mounting demonstrations to improve conditions for teachers and students.

Did similar neoliberal policies affect teachers at the university level?

During the neoliberal period, we had a premeditated abandonment of public universities. Government policy opened the door to making higher education a private for-profit business, contrary to the 1917 Constitution Article 3 that states that all levels of education should be free and public. But university faculty did not protest the changes, neither for higher ed nor for education in the lower grades. And the faculty unions and the progressive CNTE have no connections.

Students and workers in and near the University of Guanajuato have staged several important protests. Did the faculty union support them?

We don’t have one national faculty union. Each university has its own. At the University of Guanajuato in 2019, students staged a strike against rampant patriarchy, including the harassment of women students by faculty members. Our union did not take a stand.

Next door in Silao, GM workers protested in front of the plant against the fraudulent election held there that ratified a charro union contract. These workers had just formed their own independent union, SINTTIA, that sent messages of support to the feminist demonstrators. But did the faculty union do anything to support SINTTIA in its struggle? No!

AMLO recently criticized Mexican universities for being elitist, and that ruffled lots of feathers. Your reaction to his charge?

Top university officials — including even the rectors of public universities like UNAM — earn more than the president of México. These “golden bureaucracies” don’t want to lose their offensive privileges.

Public universities don’t have dorms or cafeterias, scholarships or transportation for students from distant rural communities. That tells you what class the universities expect students to come from. And they’ve designed the content of their curriculum to justify the neoliberal system.

Morena promises “transformation.” What would this look like in higher education?

AMLO has already begun creating a system of new universities to satisfy the demand for higher education from low-income families. That’s a good step, but these new universities still haven’t become completely “free.” Students have costs: room and board, textbooks, computers, internet access. New stipends are helping somewhat to alleviate those costs.

Even more important: the content of education. The right-wing National Action Party — the PAN — is today openly celebrating fascism. The PAN formed in 1939, specifically to oppose the Cárdenas socialist education program. That shows you how important the question of education has been in México. In the 2000s, the PAN government promoted a Eurocentric curriculum designed to create popular support for foreign business interests coming into México. This curriculum belittled the communal land system of the indigenous populations in México’s southern states and touted capitalism as the only way to run the world.

We should base our education instead in a philosophy of liberation. We need to lift up our own writers, thinkers, and scientists. We need to find our own ways of organizing our communities and sustaining our lands. By building on the foundation of our own resources, by learning from ordinary people, we’ll be able to transform our society, in our own particular Mexican and Latin American way. I have hope that we can do it! |

|

|

A Look Back at México’s Progressive Education Past |

|

Mary Kay Vaughan, a University of Maryland professor emerita in history, has received the Bryce Wood Award of the Latin American Studies Association for best book on Latin America published in English. We excerpt here a synopsis of that work, Cultural Politics in Revolution: Teachers, Peasants, and Schools in Mexico, 1930-1940.

In the 1930s, Mexican rural schools became arenas for cultural politics — the process of articulating and disputing definitions of culture, from national identity to the broader sense of social behavior and meaning. |

|

|

Created in 1921, the Secretaria de Educacion Publica (SEP) set up federal rural schools to nationalize and modernize rural peasants. The SEP was dominated by leftists who aimed to build a national party based on worker, peasant, and middle-class support. Their cultural program, known as socialist education, attacked superstition, religion, and the church; stressed collective learning and organization; taught productive habits such as gardening to children; and organized adults in agrarian associations and anti-alcohol and sanitation campaigns. Indigenous and multiethnic elements of popular culture were celebrated and packaged as national culture.

Teachers became explicit political actors, instructed to organize peasants and workers to press for federal agrarian and labor laws that would redistribute wealth and power. In this book, four case studies examine how this agenda played out in rural communities in Puebla and Sonora states, focusing on relationships between federal teachers; the states' conservative governors; and Mexico's most radical president, Lazaro Cardenas. The communities include two types of mestizo communities (traditional agrarian and resettled agribusiness workers) and two types of indigenous societies (the village-based Nahuas of Sierra Norte and the recently conquered, tribally cohesive Yaquis of Sonora). Each community participated in its own way in the negotiation of cultural politics through schooling in the 1930s and helped to construct a shared national language for consent and resistance — a dynamic basis for civil society unique in Latin America. |

|

|

Recent news reports and commentaries, from progressive and mainstream media,

Maureen O’Donnell, Jesus ‘Chuy’ Negrete, Chicago folklorist, writer, singer of Chicano movement, dead at 72, Chicago Sun-Times. A look back at the life of the activist Edward James Olmos has called the Chicano Woody Guthrie.

Kurt Hackbarth, The Far Right Is Lurking Within Mexican Conservatism, Jacobin. As AMLO’s transformative social programs gather stream in Mexico, the country’s conservative opposition parties are making overtures to the far right.

John Ackerman, La nueva democracia pos-COVID, La Jornada. El vacío generado por la falta de presencia ciudadana en las calles es lo que ha permitido a Lorenzo Córdova y sus aliados del bloque conservador presentarse tan cínicamente como adalides de la democracia.

Nayeli Lemoine, AMLO invertirá casi 10 mil millones en construcción de parque solar en Sonora, Polemón. El octavo parque solar más grande del mundo estará en Puerto Peñasco, Sonora.

Mexico’s new water law could be passed in 2022, Bnamericas. In 2012, a new constitutional reform declared access to water a human right, but lawmakers have failed to vote on one of the several proposals presented since 2013.

Max De Haldevang and Maya Averbuch, AMLO Defends Decree Casting Mexico Projects as National Security, Bloomberg. A new federal directive orders authorities to issue 12-month provisional permits for a swath of government infrastructure projects within five days after these permits have been requested.

Edit Porkson, “The country would be chaos”: warns AMLO, speculating what would have happened if he had not come to power, Gal Times. If the 2018 elections had not ended the chronic looting endemic in previous administrations, the Mexican president charges, the country would now be sunk. |

|

|

The Mexico Solidarity Project brings together activists from various socialist and left organizations and individuals committed to worker and global justice who see the 2018 election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as president of México as a watershed moment. AMLO and his progressive Morena party aim to end generations of corruption, impoverishment, and subservience to US interests. Our Project supports not just Morena, but all Mexicans struggling for basic rights, and opposes US efforts to undermine organizing and México’s national sovereignty.

Editorial committee: Meizhu Lui, Bruce Hobson, Bill Gallegos, Sam Pizzigati, Courtney Childs, Victoria Hamlin. We welcome your feedback. Interested in getting involved? Drop us an email! |

|

|

|

Web page and application support for the México Solidarity Project from NOVA Web Development, a democratically run, worker-owned and operated cooperative focused on developing free software tools for progressive organizations. |