|

|

|

|

The weekly newsletter of the México Solidarity Project |

|

|

|

February 10, 2021/ This week's issue/ Meizhu Lui, for the editorial team |

|

|

The Past Is Never Past |

|

You always loved grandma’s homemade bread, and the smell of fresh bread today still transports you back to her cozy kitchen. Or maybe you saw your war-time buddy get blown to pieces right next to you, and now every loud noise flashes you back into a state of horror. The past — the good and bad alike — always stays with us.

So too with countries. To understand any country’s present, we have to know its past.

Just look at the starkly different histories of US and Mexican family farmers. In the United States, white settler families gained free land, first from the British and then later from the US government under the Homestead Act — after the first peoples had been exterminated or removed. In the US, a nation born and bred in settler capitalism, individualism and private property run all through our DNA.

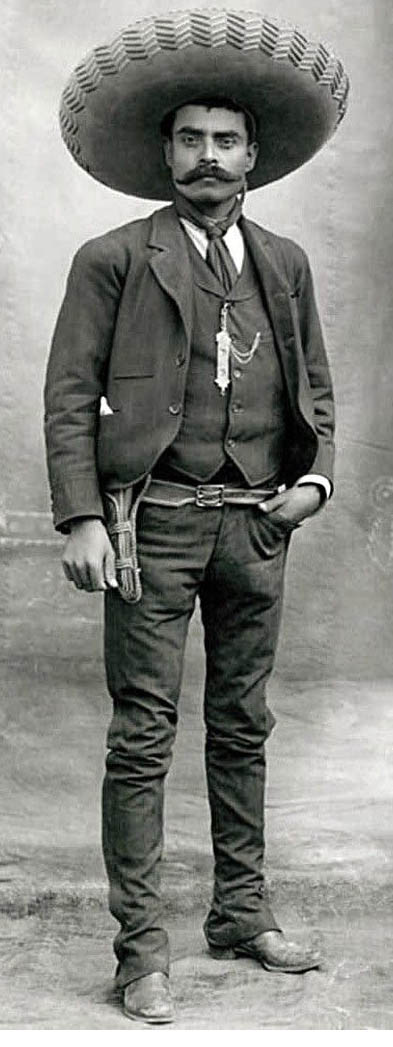

By contrast, first peoples and Mexican farmers had title to and worked on communally held land for countless generations. Then in the 19th century, with capitalism in México rising and dispossessing farmers, agrarian people rose up. They demanded the return of their land. Many fought and died for that demand in the 1910 Mexican Revolution, under the leadership of Emiliano Zapata. Since his 1919 assassination, many more have fought and died to get their land back.

Their descendants have never surrendered. How, after all, can you surrender a dream? How can you surrender a demand with roots not in mere politics, but deep in emotional memory — like the comforting smell of fresh bread or the sudden sound of a shot? |

|

|

Born in México, Tanalís Padilla has always found her nation’s turbulent past fascinating. Now a historian at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, she focuses on the history of agrarian and popular movements. Padilla, the author of Rural Resistance in the Land of Zapata, also stays engaged in the present, as an active participant in campaigns for justice in Latin America that range from Chiapas solidarity to cross-border worker organizing. How can history inform our contemporary struggles? The México Solidarity Bulletin just explored that question with her. |

|

|

The National Regeneration Movement, Morena, was founded in 2014 as a social democratic political party with a leader — current Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador — who vowed to bring about a “transformation” by defending Mexican sovereignty, ending corruption, and improving the lives of the poor. Those goals hark back to the demands of the 1910 Revolution. Did that revolution succeed?

Tanalís Padilla: Like today’s neoliberalism, the liberal policies of dictator Porfirio Diaz in the late 19th century structured the economy to put it in the hands of a few, often foreign and predominantly US entities. Mining and railroad companies, industries, and plantations all usurped land from indigenous and peasants, who were then forced to work in slave-like conditions. Diaz even allowed the Arizona Rangers to come into México and put down a strike by mineworkers in the north!

Díaz eventually signaled he’d step down, then reneged and unleashed an armed insurrection that became a social, anti-imperialist revolution. The decade-long war broke the power of the oligarchy and produced a powerful and stable state that, unlike many of its southern neighbors, did not generate a military regime.

But didn't the liberal capitalist victors betray their allies, the indigenous people, peasants, and workers who fought with Zapata and Villa? Did the common people make any gains?

The new elites would not have been able to rule without implementing serious social reform. Thanks to the unrelenting resistance of villagers to a series of post-Diaz heads of state, the Constitution of 1917 addressed the most egregious social abuses.

Article 3, for instance, established the right to a free and secular education. Article 27 gave peasants the right to land, and to hold it collectively as they had done for centuries. President Salinas did away with this provision in 1992, in preparation for NAFTA, and that triggered the Zapatista uprising in Chiapas.

Another key provision of the 1917 Constitution, Article 123, guaranteed a minimum wage, the right to unionize and strike, and an eight-hour day. Article 123 also pledged México to equal pay regardless of gender, maternity leave, and an end to child labor. At the time, the article amounted to the most progressive call for labor rights in the world.

Good on paper. But were those provisions actually implemented?

Between 1934 and 1940, President Lázaro Cárdenas distributed millions of acres of land to small farmers, built schools, and trained teachers. Cárdenas also nationalized México’s oil industry, then owned by U.S. and British companies. These companies retaliated with sanctions, but their governments didn’t invade because the Great Depression had weakened the imperial powers, who also had their attention focused on the impending Second World War.

What happened then that made social movements rise again and result in AMLO’s election? Can he fulfill his promise to create the social transformation the Mexican people sought 100 years ago?

Forty years of neoliberal policies have seriously weakened the social provisions of Mexico’s constitution. AMLO ran on a campaign to make education widely accessible, reduce poverty, and address the nation’s extreme concentration of wealth. In terms of foreign policy, he has returned to Mexico’s support for self-determination, an important move in a Latin America where the U.S. has strong-armed — and even invaded — countries to impose its will. This quite mild defiance has AMLO portrayed negatively in the U.S. press.

But AMLO is no revolutionary. He comes from the reformist pre-neoliberal PRI tradition. He focuses primarily on corruption, as if corruption sits at the root of México’s problems! AMLO has good social principles but operates within a capitalist agenda. He remains hounded by the right and has been hit with a health disaster. México will likely see progress under AMLO, but not a “fourth transformation.” |

|

|

Emiliano Zapata’s vision and visage, over a century after his death, remain as respected and beloved as ever. And contested, too, as MIT historian Tanalís Padilla explains in this analysis that originally appeared in La Jornada. |

|

Zapata: Struggle, Legend, and Memory |

|

When, in 1911, Emiliano Zapata joined Francisco Madero's fight against the dictator Porfirio Díaz (1876-1911), he did so because in his Plan of San Luis, Madero had promised the redistribution of land. At Zapata's insistence that Madero restore the lands taken from the rural villages, he was instead offered a ranch where he could retire quietly. Zapata, indignant, replied that he had not joined the Revolution to become a big landowner. Zapata would continue fighting, now against Madero, then against Victoriano Huerta and finally against Venustiano Carranza and Álvaro Obregón.

After military victories in 1915, in control of the territory of Morelos, the Zapatistas implemented the Plan de Ayala, transforming a state that the Porfirista policies had turned into a giant sugar plantation into a territory where the people now owned and controlled the land, deciding what to cultivate according to their needs and customs.

The Plan de Ayala was followed by several Zapata decrees that established a credit bank for small producers, a ministry of agriculture with seeds support, and initiatives so that not only the villages, but also the poorest peasants received land. |

|

|

A project of such dimensions had never been implemented in the country before, and Carranza and Obregón took note and took action. Defeating the Zapatistas would not only require a brutal military force, but also agrarian and other social reforms that would give legitimacy to their own limited liberal project.

The Zapatista campaign did finally end in defeat, but their struggle, vision, and ideals fundamentally determined the 1917 Constitution and the post-revolutionary national project. Zapata was assassinated in 1919, and his heirs would continue their struggle not only for material demands but also to recover the memory of the Caudillo del Sur (leader of the South) and insist on his principles of justice.

In the following decades, with Zapata’s continuing high stature in the eyes of the people, the Revolution that had become the government spread an image of Zapata stripped of all his radicalism and converted him into another 1910 revolutionary hero simply bent on overthrowing Díaz. The figure of Emiliano Zapata has been appropriated to an extreme that insults his historical memory. For example, in 1992 President Carlos Salinas announced his reform of Article 27 in front of a large image of Zapata, cynically asserting that El Caudillo del Sur would support the changes that privatized the (communal) ejido system and declared all pending land requests null and void.

But the people have long memories and long for justice. They have vindicated Zapata's legacy. From the struggle of Rubén Jaramillo who undertook the agrarian struggle, to the Zapatista veterans of the Revolution who day and night guarded the grave of General Zapata so that the government would not take his remains to Mexico City, to the EZLN that in 1994 launched its ¡Ya Basta! Campaign (Enough!) to the neoliberal reforms, to the people of eastern Morelos who today oppose the construction of a thermoelectric plant that would devastate their lands and waters, Zapata, as example, symbol and inspiration of the struggle, is still alive.

A century after his death, his fight continues. |

|

|

Recent news reports and commentaries, from progressive and mainstream media,

Pamela Starr, What AMLO Really Thinks About Biden, Foreign Policy. Mexico’s president has been a thorn in the new U.S. leader’s side, but all in the service of a constructive relationship.

John Ackerman, Regular las redes, La Jornada. La censura de parte de Twitter de tres destacadas cuentas cercanas a la Cuarta Transformación es un ejemplo reciente de como las grandes empresas digitales no garantizan las condiciones de neutralidad necesarias para un diálogo auténticamente democrático y plural.

C. J. Chivers, Risking Everything to Come to America on the Open Ocean, New York Times. The border with Mexico extends well beyond the desert. Tighter enforcement on land has driven record numbers of migrants to attempt dangerous crossings by water.

Cameron Peters, What Biden wants to do on immigration, briefly explained, Vox. Biden’s immigration plan includes a pathway to citizenship, but faces an uncertain future in Congress.

Kurt Hackbarth, AMLO Cannot Build a Transformative Political Project Through Mexico’s Military, Jacobin. Andrés Manuel López Obrador has wagered that he needs the support of the military in order to execute his progressive agenda.

Harsha Walia, Confronting the Long Arc of U.S. Border Policy, Intercept. The rhetoric of “productive” and “legal” immigrants, with the simultaneous demonization of “criminal” and “illegal” immigrants, has been the cornerstone of the Democratic Party’s immigration platform for three decades.

Christopher Blattman, Benjamin Lessing, Santiago Tobon, and Gustavo Duncan, Gang rule: Understanding and Countering Criminal Governance, SocARXIV. A useful academic look at how gangs actually operate at the community level. A briefer explainer.

David Agren, ‘It feels like a placebo’: Mexico’s vaccine program sees disastrous launch, Guardian. Mexico was the first country in Latin America to receive Covid-19 vaccines and started vaccinating health workers in December. But the pace has slowed to just 4,365 doses a day.

Mexican power bill will not lead to expropriations, minister says, Financial Post. President Lopez Obrador has sent a bill to Congress that aims to give preferential access to the grid to the state power utility, the Comision Federal de Electricidad.

Olmedo Beluche, Notas para la comprensión de las guerras de independencia de México, Supermiso. Los objetivos iniciales de los actores no necesariamente coinciden con lo que termina sucediendo al final. |

|

|

The Mexico Solidarity Project brings together activists from various socialist and left organizations and individuals committed to worker and global justice who see the 2018 election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as president of México as a watershed moment. AMLO and his progressive Morena party aim to end generations of corruption, impoverishment, and subservience to US interests. Our Project supports not just Morena, but all Mexicans struggling for basic rights, and opposes US efforts to undermine organizing and México’s national sovereignty.

Editorial committee: Meizhu Lui, Bruce Hobson, Bill Gallegos, Sam Pizzigati. We welcome your suggestions and feedback. Interested in getting involved? Drop us an email! |

|

|

|

Web page and application support for the México Solidarity Project from NOVA Web Development, a democratically run, worker-owned and operated cooperative focused on developing free software tools for progressive organizations. |