|

|

|

|

The weekly newsletter of the México Solidarity Project |

|

|

|

February 24, 2021/ This week's issue/ Meizhu Lui, for the editorial team |

|

Black/Brown Unity: Deep as DNA |

|

All the DNA testing available these days has many people surprised — even shocked — to find out who their people really are. Harvard’s Henry Louis Gates, for instance, identifies as African-American. His DNA tests revealed he has 50 percent European ancestry. Gates turns out to be literally related to the Irish-American cop who arrested him for “breaking in” to his own home! |

|

|

What makes test results like these such a shocking phenomenon? We can trace the roots of that shock deep into American history, back to the attitudes of the English settlers who wiped out the first peoples and then knew non-whites only as the Africans they enslaved — and refused to consider as fully human. In that environment, how many drops of “black blood” you had took on life-and-death importance.

In the US today, ancestry — as reflected in your features and color — still largely determines your social and economic status. But in the territories of México, relations between Africans, indigenous peoples, and Spanish colonizers took a different track, as we learn in our Voices interview this week with historian Ron Wilkins. Africans first arrived in México, Wilkins explains, neither as slaves nor conquerors, but as explorers.

Centuries later, Spain defeated the Aztec Empire and brutally worked native peoples to death in the silver mines. The colonizers also imported huge numbers of Africans to augment the labor of indigenous workers on large Spanish-owned plantations. These two subjugated populations shared their fates — and their DNA. Not surprisingly, Africans, indigenous peoples, and Afro-Mestizos would later join the Revolution. But they would be more than mere foot soldiers. They played leading military roles. General Vicente Guerrero, son of an Afro-Mestizo father and an indigenous mother, became the second president of México in 1829. The United States would not have a president of color until 2009.

Black History Month in the US brings to light the hidden stories of Black perseverance and achievement. But so much remains hidden. The Mexicanos who have lived for generations in what became the US Southwest have African and not just Spanish and indigenous ancestry. The US and México today amount to two overlapping nations, with African Americans and Mexicans two overlapping peoples. Black/brown unity amounts to more than just a political perspective. Black/brown unity runs as deep as DNA. |

|

|

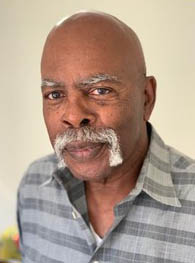

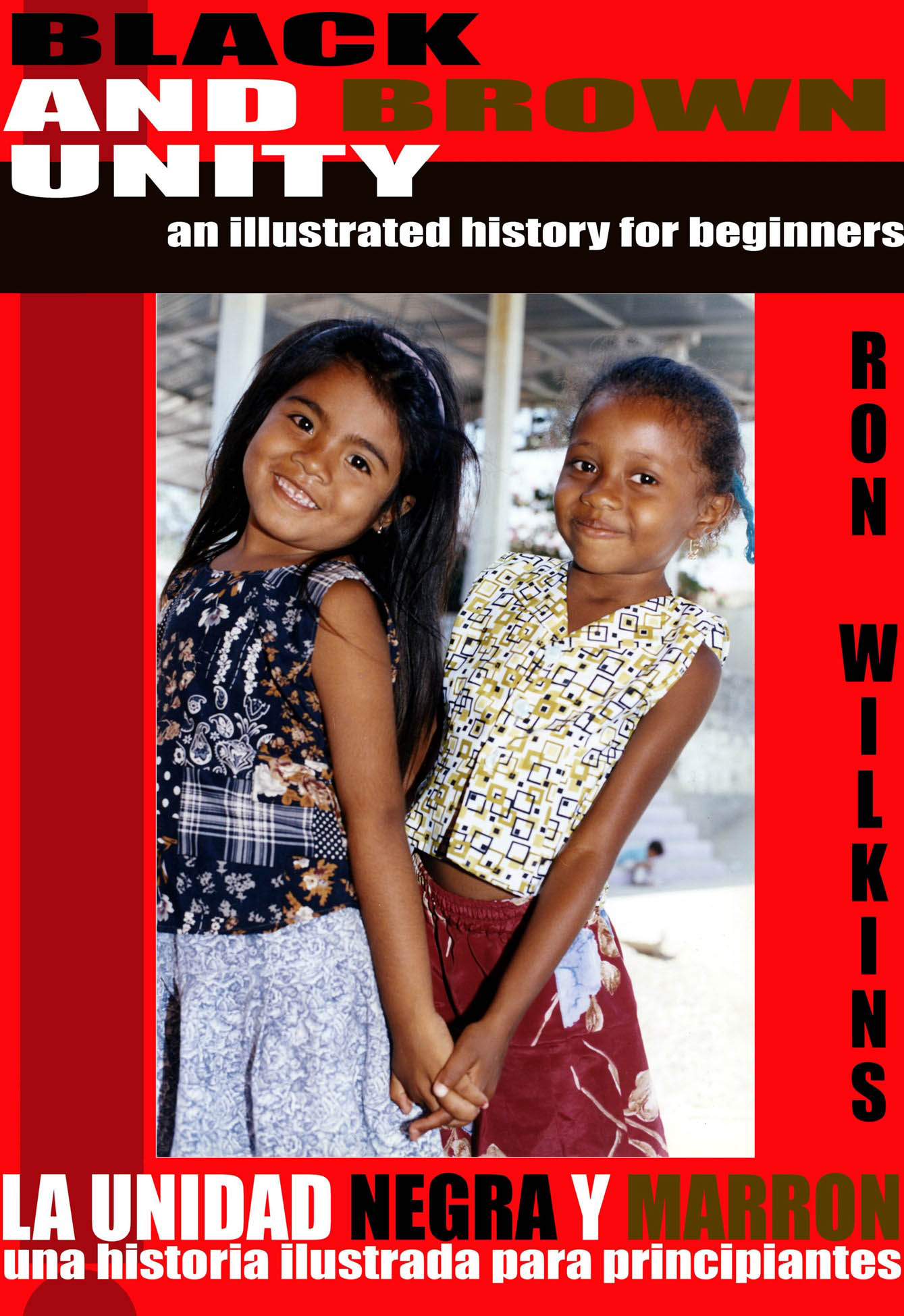

Historian Ron Wilkins, recently retired from California State University-Dominguez Hills and West Los Angeles College, has spent years detailing what he sees as the “long and shared history of Blacks and Latinos struggling together against racism and injustice,” a history “not widely known.” That story, Wilkins believes, needs to be taught in every school. A good step toward that goal would be placing his children's book, Black/Brown Unity: An Illustrated History for Beginners, in every school library. For more, check the Wilkins website: blackbrownunity.org.

You’ve been on a mission to publicize the history of the relationship between African Americans and Mexicans. What makes this relationship so important? |

|

|

Ron Wilkins: Everywhere I’ve lived growing up, in South LA, has been among Mexican people. We share space today. We need to know each other and how our histories have brought us together.

How far back does the connection between Africa and México go?

Back way before México came to be. Egyptian soldiers and mariners traveled to the region and encountered the Olmec people around 800 AD, about when you started to see pyramids built in México.

Many of the fighters for México’s Independence from Spain, in the years from 1810 to 1821, had been slaves. They joined the Revolution because its leaders promised that the struggle for independence would also end slavery. The revolutionary army that fought under a black flag became known as the “Ejército Moreno” — the Dark Army — because so many of its fighters had African roots. Revolutionary General Vicente Guerrero had an Afro-Mexican father. Guerrero banned slavery when he became president of México in 1829.

From looking at photos of historic Mexican figures, you see that many had African features and dark complexions, signifying African descent. Among these historic figures: the revolutionary leader Emiliano Zapata and muralist Diego Rivera. |

|

Do you see a connection between Mexicans and people of African descent in the US?

Before the annexation of Texas, Mexicanos/Tejanos helped perhaps 5,000 or 6,000 Africans escape from slavery by going south, deeper into Mexico. The owners of these escaped slaves traveled to México to demand their return, but the Mexican government refused. In 1836 after the fall of the Alamo, Mexican forces traveled from plantation to plantation in Texas, setting slaves free and giving them title to the land they had been working!

In 1857 the U.S. Supreme Court declared during the trial of the enslaved Dred Scott and his wife that “Black people had no rights that whites were bound to respect.” That same year, the Mexican Congress declared that any enslaved person who set foot on Mexican soil would be from that moment free. I often speak to African American audiences and tell them that Mexicans did far more for us than we did for them. That shocks people!

Do African American and Mexican history intersect in other ways?

In the 1930s and 1940s, Black artists such as Elizabeth Catlett went to Mexico to collaborate with Mexican muralists. And if it wasn’t for the Mexican baseball leagues, Jackie Robinson might not have broken the color line in the US Major Leagues. Negro League players commonly traveled to play in the Mexican League, where they rated as worthy opponents.

In 1938, a Mexican team started hiring Black players, beginning with famed Negro League pitcher Satchel Paige. The Brooklyn Dodgers noticed how well these Negro Leaguers played in the Mexican teams and signed Jackie Robinson. But the widely promoted film “42” about Jackie Robinson doesn't mention Mexicans at all. The movie treats them like “the elephant in the room,” with nothing about their contribution! |

|

In the US, people of African and of Mexican descent have suffered discrimination and subordination. Have they ever joined forces?

Many times. We’ve had solidarity between our communities on labor issues, on desegregation, for ethnic studies — so our children can see themselves represented — to name just a few battlegrounds.

But we’ve also had misunderstanding, more so today than in the 1960s and 1970s, and that division hurts both groups. People need to know the history. That knowledge can help us unite to win our rightful places in society. |

|

|

|

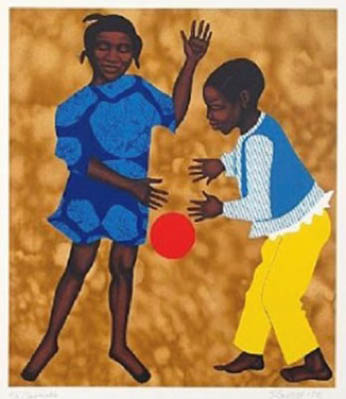

Elizabeth Catlett, 1915-2012: African American Mexican |

|

Born in Washington, D.C., the artist Elizabeth Catlett traveled to Mexico when she was 31, curious about post-Revolution mural painting. Catlett liked to note that she arrived in Mexico City one night and the next evening went to the Taller de Gráfica Popular — the People’s Graphic Arts Workshop — where she found “a lot of us, all artists,” soon-to-be famed figures like Leopoldo Mendez, Pablo Higgins, and Francisco “Pancho” Mora.

This community of like-minded artists, as well as the repressive atmosphere in the post-war United States, would convince Catlett to make México her home for the rest of her life. |

|

|

Catlett saw parallels between the oppression of “both my peoples,” African Americans and Mexicans. Fieldworkers, laborers, mothers and fathers, homeless children, political resisters: Her work expresses the extraordinary dignity in ordinary people’s daily acts of survival and constantly illuminates opposites: anger and outrage, strength and resilience, beauty and joy, oppression and ugliness. |

|

|

|

An artist-activist, Catlett was arrested in 1958 during the Union of Railroad Workers strike in Mexico City. The same year she became the first woman hired to teach fine art at Mexico City’s Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico (UNAM) and later became the head of the prestigious university’s sculpture department. Such a position, in the United States of that era, would be totally off limits to African American women.

Catlett became a Mexican citizen in 1962. Her radical politics would then deny her entry into the United States until 1971, when she gained a visa to attend the opening of her solo show at Harlem’s Studio Museum. |

|

Elizabeth Catlett’s technical skill would never undercut the unique power of either her artistic vision or her broader vision for humanity. She remains an artist for the ages, with a universal but specific message for racial justice and social transformation.

“I have always wanted my art to be of service to my people,” as she once noted. “We have to create an art for liberation and for life.” |

|

|

|

Recent news reports and commentaries, from progressive and mainstream media,

Ioan Grillo, Slow the Iron River of Guns to Mexico, New York Times. México’s Foreign Ministry estimates that over 2.5 million guns have flooded into México from the United States in the last decade, fueling a violence that terrorizes communities and stifles the nation’s growth.

Dave Graham and Daina Beth Solomon, Mexican tourism body aims to spark state-backed solar blitz, Reuters. Mexico is crafting a plan to promote state-backed solar power generation that could spur well over $1 billion in investment, benefit local communities, and help the government meet environmental targets.

Mauricio Rabuffetti, Wealth Tax: Inequality Solution For Latin America? Agence France-Presse. The richest 1 percent in the region holds 41 percent of the region’s wealth, but only contributes 3.8 percent of the public purse.

Foreign minister, México City mayor lead poll to succeed AMLO in 2024, México News Daily. The survey asked who could best defend the legacy of President López Obrador.

Censuran protección de AMLO a Salgado, Reforma. Activistas, escritoras, investigadoras y actrices exigieron ayer al Presidente Andrés Manuel López Obrador romper el pacto de machismo al mantener a Félix Salgado como candidato de Morena a la gubernatura de Guerrero, a pesar de que enfrenta acusaciones de violación y abuso sexual.

Rubén Sierra, Latin America finds its own answers to produce COVID-19 vaccines and save lives, Council on Hemispheric Affairs. Oxfam and Global Justice Now have accused the biggest Covid vaccine producers — Pfizer, Moderna, and AstraZeneca — of strangling the global vaccine supply. Cuba, Mexico, and Argentina are providing a counter model.

ONU le da la razón a AMLO: 10 países acaparan el 75% de las vacunas, Polemon. Al igual que el Presidente Andrés Manuel López Obrador, el Secretario General de las Naciones Unidas denunció que el 75 por ciento de las vacunas contra Covid-19 que se han aplicado hasta ahora están concentradas en 10 países desarrollados. |

|

|

The Mexico Solidarity Project brings together activists from various socialist and left organizations and individuals committed to worker and global justice who see the 2018 election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as president of México as a watershed moment. AMLO and his progressive Morena party aim to end generations of corruption, impoverishment, and subservience to US interests. Our Project supports not just Morena, but all Mexicans struggling for basic rights, and opposes US efforts to undermine organizing and México’s national sovereignty.

Editorial committee: Meizhu Lui, Bruce Hobson, Bill Gallegos, Sam Pizzigati. We welcome your suggestions and feedback. Interested in getting involved? Drop us an email! |

|

|

|

Web page and application support for the México Solidarity Project from NOVA Web Development, a democratically run, worker-owned and operated cooperative focused on developing free software tools for progressive organizations. |