|

|

|

|

The weekly newsletter of the México Solidarity Project |

|

|

|

November 10, 2021/ This week's issue/ Meizhu Lui, for the editorial team |

|

‘Artivism’: Art as a Hammer for Justice |

|

The term “artivism” traces back to the late 1960s, years when Chicano activists in East Los Angeles were producing artworks that fused graphics and words to educate and mobilize for Chicano liberation. “Artivism” then fell out of use for several decades until the San Diego-based performance artist Ricardo Dominguez began popularizing the term in the 1990s.

The 1997 Acteal massacre in Chiapas had outraged Dominguez. Some 45 men, women, and children in a Zapatista community lost their lives in that tragedy, all killed by a right-wing paramilitary group. Dominguez channeled his outrage into a new way to practice global solidarity: the Electronic Disruption Theater. During the civil rights movement, protestors blockaded buildings. Through the Electronic Disruption Theater — software that could blockade a website if enough people used it at the same time — contemporary activists could choreograph blockades that shut down oppressive digital workspaces. |

|

Today, the use of “artivism” is cropping up all over. But there’s no need for a special label for the revolutionary art that has so long flourished in México. In our interview this week, artist Vicky Hamlin explores the work of activists at El Taller de Gráfica Popular, the People’s Graphic Workshop — not “studio” — in México City. Starting in the late 1930s, these activists rejected the notion that art must remain the domain of a few talented souls who sell their work for millions to elites who keep the art under lock and key. |

|

|

The Marxist playwright and poet Bertolt Brecht did much of his finest work during the Taller’s heyday. Mexican and US artist/activists then and now would certainly agree with one of Brecht’s most famous declarations: “Art is not a mirror held up to reality, but a hammer with which to shape it.” Let the hammers ring! |

|

|

Vicky Hamlin, a “red-diaper baby” and painter from an early age, has lived a life that’s combined art, her feminist and socialist politics, and work as a welder. Hamlin’s activism has helped force open the doors of the building trades to women. Through Oakland’s Tradeswomen, Inc. and as a union steward, she spent years challenging macho culture and mentoring younger tradeswomen. Her well-known paintings and photos of tradeswomen combine art and politics and encourage young women to claim equal status with men. Hamlin is currently serving as the cultural editor for the México Solidarity Project.

Your father, the “artivist” Marston Hamlin, studied art in the US, but then left to go to the Taller de Gráfica Popular in México City. What role did the Taller play? |

|

|

Vicky Hamlin: Three well-known artists, two Mexican and one American, had founded the “People’s Graphic Workshop” — an internationalist project right from the start — as a print collective in 1937. The Taller would become a hotbed for revolutionary-minded artists, supporters of the ideals of the Mexican and Russian Revolutions, then still recent events.

What drew your father to the Taller?

Like many of the Mexican artists, such as the muralists Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros, he belonged to the Communist Party, and both the Mexican and US party branches were part of the Third International founded by Lenin. The Taller was a dynamic place, both a school and a workshop where artists learned printmaking and created pieces together — the opposite of the individualistic approach to art in the Western tradition. They produced art accessible to all that carried messages supporting social change. |

|

After the Taller, my father returned to the US and worked as a precision machinist and as an art teacher. He continued his political activities in the CPUSA. But in 1953 he was hauled before the infamous House Un-American Activities Committee. He refused to testify, saying that he did not recognize the panel’s authority. After that, he was blacklisted and had to find other work.

Many people consider art as something “above” politics and deem socialist art to be “propaganda,” not art. |

|

|

That’s a Western and elitist view. We’ve always had art by and for the people. México, unlike Europe, has had a long history of indigenous art, much of it —pottery and weaving, for example — designed for daily use.

México also has a long tradition of murals and printmaking. The Taller produced posters in the 1930s to help President Cárdenas promote his social programs. During the same period, artists in the US were similarly hired to promote FDR’s New Deal, and Mexican and US artists collaborated during those years.

Did US artists continue to work at the Taller after the Great Depression?

The African American sculptor and graphic artist Elizabeth Catlett and her then-husband, the printmaker Charles White, went to Mexico in 1946 to study the murals and graphic art produced after the Mexican Revolution. She stayed at the Taller for 20 years. Another more contemporary example: Rini Templeton, who moved to México and joined the Taller in 1974. We’ve all seen and maybe used her distinctive prints. She let everyone use her art for free. She didn’t want to “own” art. She made it to be useful to people in struggle.

Like father like daughter, you’re both a visual artist and a political activist. Do your own paintings serve a political purpose?

I’ve thought about that all my life. As I grew older, I looked for more nuanced and long-term political messages, ones that lasted past single issues. Now I paint people in social situations, some political, some not, but always with an eye for what makes people tick, and especially what “ordinary” people are thinking, feeling, and doing.

I paint women working in non-traditional occupations, especially the building trades and construction. Women had to fight to get those jobs and had to support each other to survive harassment on the job from male co-workers. My paintings celebrate and normalize their experience. |

|

What role does art play in building solidarity today?

The lives of working and struggling people must open to the light of day, to bring strength, hope, and resilience to those who will shape our future. The fight against the rich, the 1 percent-funded right-wing, has become supremely important. These issues need illuminating, but art can also bring sanity and unity to those seeking to understand how we got here. Right: Vicky Hamlin, “Me and My Truck.” |

|

|

|

Remembering and Honoring the Taller de Gráfica Popular |

|

Nothing less than the desire for worldwide socialist revolution motivated the artists of the Taller de Gráfica Popular. Some of the mid-20th-century’s most influential and revolutionary artists participated in the Taller, towering influencers like the muralist Diego Rivera. Taller artists didn’t just create art. They literally fought fascism in the 1940s and organized and engaged in efforts to build cross-border solidarity and support. We offer here a tiny sampling of their work. |

|

|

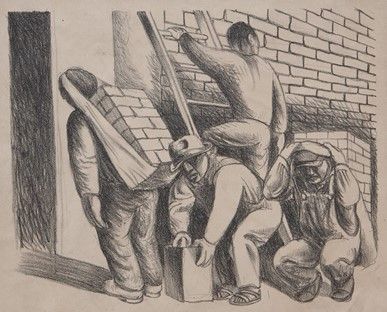

From People’s Graphic Workshop, Prints of the Mexican Revolution: 85 engravings by the artists of the Taller de Grafica Popular. Mexico: Mexican Prints, 1947. |

|

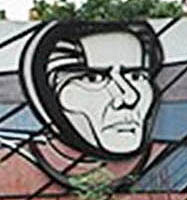

This David Alfaro Siqueiros portrait of Leopoldo Mendez, a co-founder of the Taller de Gráfica Popular and its leader for 25 years, rests on the outer wall of the Polyforum Cultural Siqueiros in México City. |

|

|

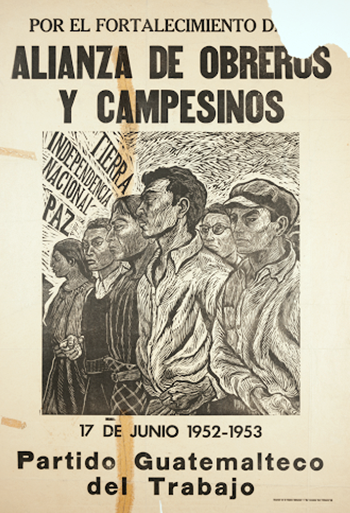

To Strengthen the Alliance of Workers |

|

|

|

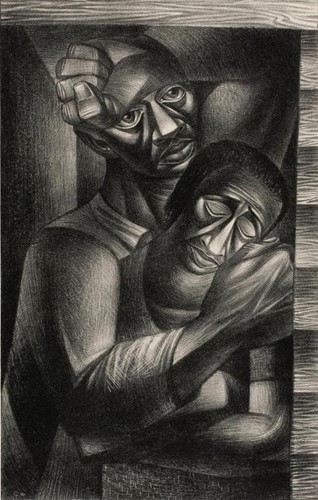

Charles White, an African American printmaker, produced this lithograph entitled Black Sorrow at the Taller in 1946. |

|

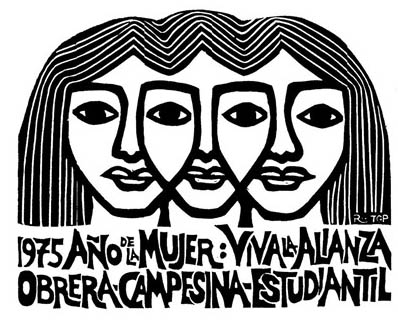

At the Taller in 1975, US artist |

|

|

|

Recent news reports and commentaries, from progressive and mainstream media,

Settlement negotiations for separated families become political issue, Border/Lines. The 2018 “zero tolerance” policy and its earlier pilots — often known simply as family separation or “kids in cages” — has now exploded back into public view.

John Ackerman, Por un Morena al servicio del pueblo, La Jornada. La dirigencia de Morena debe escuchar a las bases y rectificar de inmediato.

Giuseppe Luca Scaffidi, Activists (and a robotic arm) help women access abortions in México, Il Manifesto. Clandestine networks of activists have helped Mexican women for years. Now they’re looking across the border into Texas.

Mexican president slams COP26 ‘hypocrisy,’ AFP. Mexican President López Obrador last week slammed participants in a major UN climate summit, accusing them of failing to address the root causes of the crisis and pointing to their use of private jets.

Samir Tounsi, Mexico's heritage 'not for sale,' culture minister says, Yahoo News. Alejandra Frausto is lamenting that “cultural heritage has become an object of commerce” despite being part of “the identity of peoples.”

Eric Martin, US Expresses ‘Serious Concerns’ Over Mexico’s Electricity Plan, Bloomberg. The United States has “serious concerns” about the nationalist electricity reform proposed by México’s president, says ambassador Ken Salazar, echoing congressional criticism of México’s treatment of private firms. |

|

|

The Mexico Solidarity Project brings together activists from various socialist and left organizations and individuals committed to worker and global justice who see the 2018 election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as president of México as a watershed moment. AMLO and his progressive Morena party aim to end generations of corruption, impoverishment, and subservience to US interests. Our Project supports not just Morena, but all Mexicans struggling for basic rights, and opposes US efforts to undermine organizing and México’s national sovereignty.

Editorial committee: Meizhu Lui, Bruce Hobson, Bill Gallegos, Sam Pizzigati. We welcome your suggestions and feedback. Interested in getting involved? Drop us an email! |

|

|

|

Web page and application support for the México Solidarity Project from NOVA Web Development, a democratically run, worker-owned and operated cooperative focused on developing free software tools for progressive organizations. |