|

|

The weekly newsletter of the Mexico Solidarity Project |

|

Every issue archived online at mexicosolidarityproject.org/archives/ |

|

August 06, 2025 |

|

|

|

Against the Wall: Patrolling the Border |

|

Meizhu Lui, for the editorial team |

|

|

The border wall in the Imperial Sand Dunes, 20 miles west of Yuma, AZ, on February 25, 2019 U.S. Customs and Border Protection: Photo by Jerry Glaser |

|

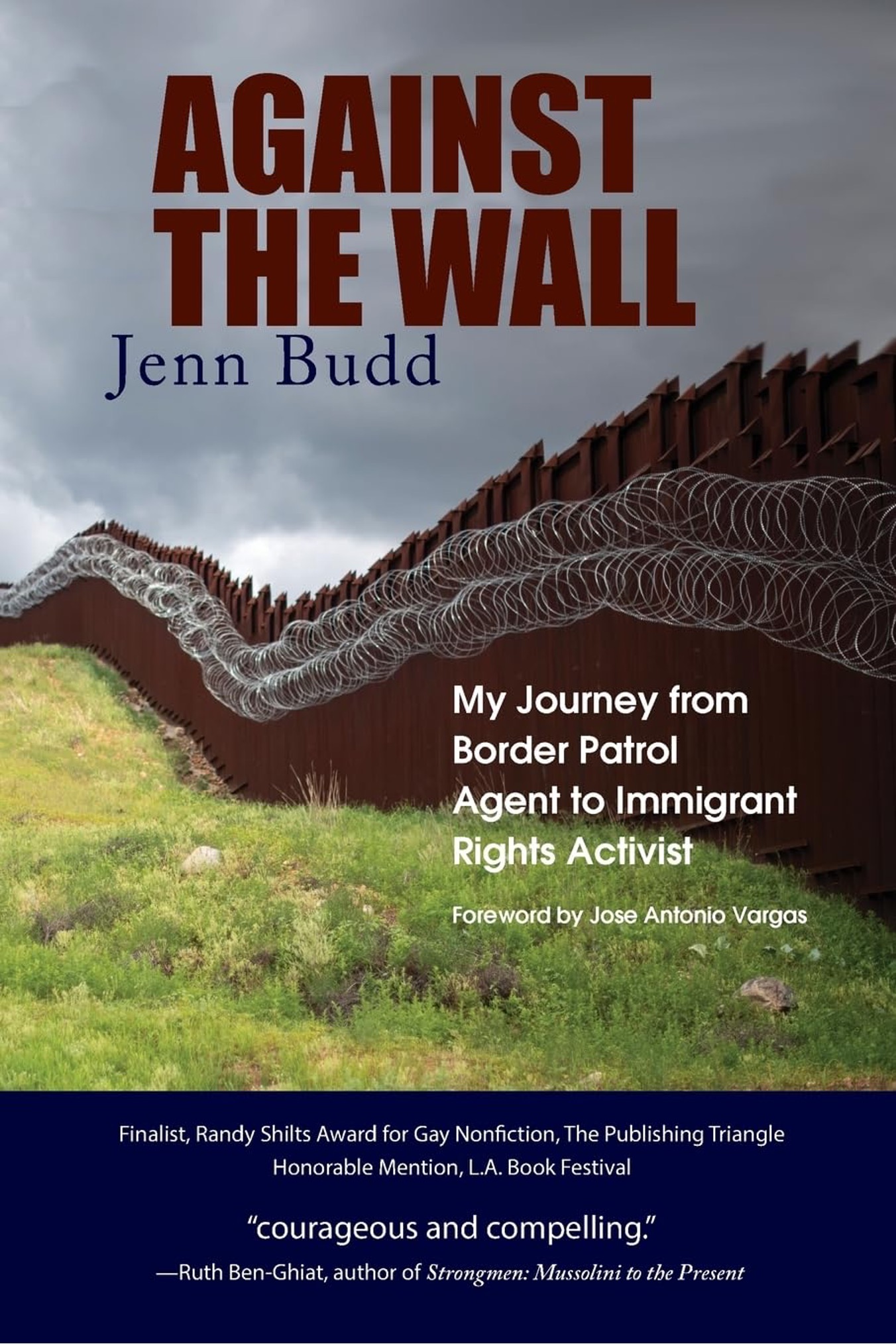

Beginning in 1995, Jenn Budd wore green as a US Border Patrol Agent, as a Senior Patrol Agent, Acting Supervisor, and in Sector Intelligence - until 2001 when she resigned in protest.

Since 2015 she’s been a fierce critic of the Border Patrol on national and local news media, including the New York Times, Newsweek, National Public Radio, Telemundo and on her own podcast. Her book, Against the Wall: My Journey from Border Patrol Agent to Immigrant Rights Activist, was a finalist in the 2023 Publishing Triangle Awards for the Randy Shilts Award in LGBTQ non-fiction writing, and she’s a sought-after consultant on migrant issues.

How did she go from a Border Patrol agent moving up the promotional ladder to a fearless immigrant rights activist? She tells you in this week’s interview. |

|

|

Jenn Budd: Telling the Story |

|

Why did you decide to work as a Border Patrol agent?

I grew up in Alabama with a mom who was an alcoholic and mentally ill. After graduating from college in 1993, I was looking for a job. To be honest, I didn’t research it before applying. I saw they were sending agents to California. Given my home situation and being a gay woman, I wanted to get as far away from Alabama as possible — California sounded great. |

|

|

Jenn Budd, 2022 |

|

|

November, 1995, graduation |

|

Were there other women?

Five percent. I was told by other women that I could expect to be sexually assaulted and that the Border Patrol had a “rape culture.” And yes, I was raped by another trainee — and then had to work with my rapist. If we tried to complain, we were told, “Don’t make the Border Patrol look bad.” It’s to test you to see if you will “bleed green” (be unquestioningly loyal to the Border Patrol, ed.). I just wanted to get assigned to my work station and prove that I could be a good agent. I passed, and was sent to Campo, California, in a mountainous area southeast of San Diego.

What was an ordinary day on the job like?

There were 50 agents assigned to 32 miles of border; there were times when I had 15 miles to patrol on my own.

Before 9/11 we mostly searched for migrants by foot. Some agents liked to scare the migrants. If they saw a group, they’d yell, “La Migra!” and laugh when the people ran and scattered; I never did that. |

|

We found a lot of dead people — men, women, children. After deterrence policies started in 1994 when they built the wall, migrants had to use more dangerous routes to get to the border, and we saw more and more deaths.

We were taught to destroy any food and water we found; I also slashed the bottles open. Once, a 10-year-old girl was picked up and given to me to take care of; she had gotten separated from her mother. But she was smart and kept walking toward the distant sound of traffic. Along the way, she found a jug of water; migrants often leave water for others. I realized that that water saved her life. After that, I never emptied water jugs.

I thought I’d be catching Mexican men drug dealers; that’s what we were told. But my first arrest was a family. |

|

|

Campo, CA, Acting Supervisory Border Patrol Agent, 2000 |

|

My mom asked me what that felt like. I told her, “I felt kind of like a Nazi... but I’m sure I’ll catch criminals soon!” But we almost never caught drug dealers, just marijuana if anything. Nobody’s gonna waste millions of dollars to bring cocaine or fentanyl on the back of a migrant!

The worst time for me — the bloodiest — was a one-month detail I volunteered for in Indio, California, with some of my fellow agents. We had only worked the high mountains, and this was a flat desert. If we thought they died fast in Campo, it was nothing like this. Migrants would ride the trains. At a checkpoint, I got up on the top of a two- or three-story ladder as the spotter. From there, I could see migrants running across the desert. I got on the radio to the agents below to arrest them. After they brought them in, they went back to look for more. They found so many dead, three and four at a time. I had just seen those same people 30 minutes before, and now they’re dying. After all the hiking, heat, lack of water — once they start running, they just drop, drop, drop.

Was the job dangerous? What was the effect on the agents?

In the years I worked, 1995 to 2001, we sometimes shared the fate of the migrants — getting lost in the desert, heat stroke, and so on. But overall, the Border Patrol is the safest police job there is, because 99% of the people we arrest are not criminals; they’re not armed and dangerous. How could I, at 5 foot 6 inches and maybe 120 pounds, arrest a hundred men by myself? Because they knew a lot of green men were behind me. Very few of us died, and the main causes of death were driving too fast on dirt roads and suicides — because of the brutality we engaged in and witnessed. Today, the number one killer of Border Patrol agents is COVID, and next, suicide.

My good friend, I’ll call him Jacob, came with me on the Indio detail. Every night, we drank massive amounts of alcohol. Jacob wouldn’t be able to function until about noon the next day. On one of the last days, the two of us were on the way to the checkpoint, and we came upon guys from the midnight shift. We looked down the road, and a migrant had gotten hit by a semi, and the guys were laughing. “Look, his arm’s over there, blah blah blah.” I told Jacob we had to get to the checkpoint. He said, “I can’t do it. I need alcohol.”

Alcoholism, PTSD, suicides — when you are involved in violence, it boomerangs. The Nazis had the same problem; the soldiers shooting the Jews were traumatized. That’s why they came up with the death camps. Migrants suffer the primary trauma. Then Border Patrol agents suffer secondary trauma, and then the attorneys, the shelter workers, those who drop water and so on suffer tertiary trauma, and it goes on and on.

Agents quit. In the late 90’s we were losing more agents than they could hire.

Why did you stay as long as you did? What made you quit?

I felt that I could do the job in a humane way. Often, I would sit with the migrants in my custody when I discovered them on the mountain, and we’re laughing. |

|

|

From Budd’s x post: “Out of nearly 8,000 asylum seekers, they found 1 criminal.” |

|

They were good people, and we treated each other with respect. I never had a migrant try to rape me like Border Patrol agents did to both migrants and women agents, or pull a gun on me. I have saved migrants' lives, and they have saved mine. Once, I nearly fell off the edge of a cliff, and a migrant reached out and pulled me back.

There were other things I felt good about; for example, I took a big risk to contain a car on fire until the firefighters got there, preventing it from spreading into Pine Valley and destroying homes. I got commendations I’m proud of. |

|

I went back to Campo. But after Indio, I realized that I was becoming angry and losing my temper with the migrants I was taking through the process. I needed to get out of the field. That’s why I applied for Sector Intelligence.

I found out that the head of Campo Station was organizing the smuggling of narcotics in our area. I went undercover in an old beat-up ride to investigate, but within five minutes, I heard on my walkie that someone had called in my description. He had lookouts. A sheriff showed up, and I got sent to the station. I knew I was in trouble.

The boss pinned me in a chair and said, “You caught me, and you’re going to shut up about this. And if you say anything, I’m going to put you in a closet for the rest of your life. Understand?” I said, “Yes sir.”

Before I could even sit down in my office, my direct supervisor, the head of Sector Intelligence talked to me. He said they could create a promotional position for me “to keep me safe.” I said, “I’m not that type of woman. I can’t be bought off.” He said, “Think it over.”

When I got home, I had a message. Go to Campo for a midnight shift. I was the most senior patrol agent, the highest rank before management, and the post they assigned me to was for a trainee. It was right next door to the Mexican border where the drugs were coming across, and they wanted me to sit 20 yards off the fence. I said, “That’s not safe!” but they said that’s how we do it now.

At about 3:00 AM, automatic weapon fire starts coming across. I was a sitting duck; the shots hit the rocks right outside my driver’s side door. |

|

They could have killed me if they wanted. I turned around and drove about 100 to 200 yards where I could hide my truck. I was calling the station, calling Sector. No one in my zone is answering. Then I saw a car on the road coming toward me, and I’m like, Shit! I pulled my gun….Then I see it’s my boss. He says, “Have you learned your lesson?” |

|

|

U.S. Border Patrol agents run down a dirt road amid swirling dust stirred up by a helicopter during a search for people who had crossed into the United States illegally and were hiding in heavily wooded areas and sugarcane fields near McAllen, Texas. Photo by Mike DuBose, UMNS, 2018 |

|

That night was the last time I wore the uniform.

Now you’re on a different mission, to expose the truth about migrants and the Border Patrol. What can be done?

Unlike in the 1990s, the majority of migrants today are not Mexicans looking for work. Most are seeking asylum, and we treat them like criminals. And Democrats refuse to explain why an asylum system is essential for national security. When you close the asylum system, as has been done, the border is out of control; we don’t know who’s coming in. |

|

|

Guadalupe, Texas: Adopt a Water Station” program sponsored by Humane Borders: Photo: Laurie Cantillo |

|

And people are still coming in all the time; they don’t keep track of the ones who get away.

We need to invest in a robust asylum system where people are checked appropriately and contained humanely for no more than a week, in a place where they can stay together as a family, instead of in detention facilities where 70% of the people aren’t criminals. Then the Border Patrol could focus on the people who really are problems.

I don’t think I’m going to see that in my lifetime. But we can still have a smart and humane way of handling migrants. |

|

We could have just as many new jobs as we have with this punitive system if we hired people who teach ESL, who can get people transportation to the places where they have family, people who make sure they get to their immigration appointments and social workers to get them help for their trauma. If we had people with those kinds of jobs, we wouldn’t have migrants and agents alike dying in the mountains and deserts.

So I’ve become a full-time activist against the Border Patrol and ICE, using talks about my book, interviews and a Substack to inform people about the reality of the migrant situation and what the Border Patrol does. I use the money I get from Substack subscriptions to fund a large water station in the desert and to support families that are victims of the Border Patrol.

The people looking for ICE jobs today may just see a pretty good paycheck and not have a clue what they’re getting into; most don’t see the bigger picture. I can see what many of the agents are not seeing — the lies we’re told about how migrants are criminals, the rape of migrants and women agents alike, and the corruption at the top. This is the culture of the Border Patrol, ICE and CBP. Some agents say after reading my book that I’m crazy. But there are also a lot of old Border Patrol agents who call me and thank me for what I’m doing.

I’m at the age where I’m like, yeah, I’m going out with a bang! I’m going to tell the story. |

|

|

Members of the Southern Border Communities Coalition condemn Operation Gatekeeper and modern border policies on Oct. 1, 2019. Speaking is Pedro Rios, director of the U.S.-Mexico Border Program for the American Friends Service Committee. Jenn Budd, second row. |

|

|

Jenn Budd, Against the Wall |

|

|

|

|

|

Joe Navarro is a Chicano poet, creative writer, socialist, community activist and teacher living in Hayward, California. He is a contributor to The Cost of Privilege: Taking On the System of White Supremacy and Racism (Camino Press 2007) and many other publications. |

|

I Am |

|

I am the result of a unique

historical experience. I am of

the seed that was sewn of this

Earth. I am the heart beat of

many millenniums. I am a

multi-layered, multi-dimensional

phenomenon that can’t be wrapped

in a neatly secured one-dimensional

package. I am the dream of

ancient wisdom. I am the

profound depths of physical,

spiritual and intellectual wonders

that haunt modern thought.

I am the descendent of survivors

who’ve sought to live when

they were doomed to die.

I was born in a dream and

lived in a nightmare

through my dreams.

I am the infusion of genetic

codes and a diaspora of cultural

eclecticism. I am a

barrio beat brother…aztlaneco.

I am the confusion and diffusion

of worlds colliding. I am the

crystal clear vision of the future.

I am the contradiction working

against itself. I am a

sorrow song and a blues corrido.

I am Cuauhtémoc’s last breath

and Zapata’s first inspiration. I am

the stroke of Frida Kahlo’s brush

and Sor Juana Inez de la Cruz’s

polemic. I am Dr. King’s

dream and Malcolm X’s

call for self-determination. I

am John Brown’s cry for justice

and Aretha’s call for r-e-s-p-e-c-t.

Soy nieto de campesinos e

hijo de urban factory workers.

I am a home-grown, urban

barrio warrior…born in a

cross-cultural, evolutionary

tradition called Aztlan. I

am hijo del sol,

hermano del corazón and

soul brother. I am the

intersection of dreams, ideals

and aspirations. I am the

righteous indignation of centuries

ready to explode. I am

a complex socio-psychological

deposit of consciousness that

transcends millenniums and cultures.

I am the dialectical outcome

of resistance to oppression. I

am Chicano, a concept that can’t

be easily explained.

2013, Joe Navarro |

|

|

|

Recent news reports and commentaries, from progressive and mainstream media, |

|

Natascha Elena Uhlmann, Independent Union Loses Bid to Represent Second Mexico GM Plant Labor Notes. SINTTIA alleges that the Carlos Leone union received support from GM management. After workers voted out their company union, a CTM affiliate, in 2023, the company installed a “labor council” at the plant, largely made up of CTM supporters.

Salvador García Soto, El bloque anti-4T que coopera con EU El Universal. Y es que, de acuerdo con información de inteligencia que manejan en el gobierno federal, hay todo un grupo de políticos mexicanos opositores al régimen morenista, que llevan ya varios meses colaborando y cooperando con instancias del gobierno de Donald Trump, como la oficina del secretario de Estado, Marco Rubio.

Eduardo García, Alfredo Corchado & Alyda Muela, Tariffs and judicial chaos shake investor confidence in Mexico: ‘Everything has been put on hold’ Guardian. Growing wave of uncertainty is freezing investment plans in Mexico, rattling business leaders in the US and abroad.

Viri Ríos, ¿Cómo salieron de la pobreza 10 millones de mexicanos? El País. La respuesta yace indiscutiblemente en las reformas laborales de Andrés Manuel López Obrador, ya que los datos muestran que lo que más mejoró fue el ingreso en México.

Sheinbaum and Trump Agree to 90-Day Delay on U.S. Tariff Hike for Mexican Goods Telesur English. “Our strategy of keeping a cool head, staying composed, and firmly defending our principles has worked,” she said. Nevertheless, Sheinbaum acknowledged that Mexico’s proposals to reduce the trade deficit were left out of Thursday’s negotiations.

Arturo Sánchez Jiménez, Crea CSP comisión para reforma electoral; Pablo Gómez la encabeza La Jornada. De acuerdo con la información oficial, esta comisión tendrá como primer objetivo realizar un diagnóstico profundo sobre el estado actual del modelo electoral y de partidos en el país. Posteriormente, se encargará de elaborar una propuesta de reforma legislativa que responda a las necesidades de los tiempos actuales, colocando en el centro la democracia y al pueblo mexicano.

Adrian Padeanu, Nissan Is Closing Its First Factory Built Outside of Japan Motor1. All vehicle production at CIVAC in Cuernavaca will be relocated to another site in Mexico, located in Aguascalientes.

Juan Carlos Miranda Arroyo, El evangelio de las competencias en educación Profelandia. El movimiento político de regeneración nacional (hoy gobierno federal) no tenía (ni tiene) proyecto educativo alternativo para el país.

Sam Levin, Dropped cases against LA protesters reveal false claims from federal agents The Guardian. Records show border patrol gave inaccurate testimony about people it jailed. Prosecutors now face ‘embarrassing’ dismissals.

Jorge Zepeda Patterson, La (in)conveniente soledad de Claudia Sheinbaum El Milenio. i bien es cierto que ella había recibido el bastón de mando y obtuvo la Presidencia, también es cierto que heredó un diseño político que, en la práctica, entregaba el Congreso a sus ex rivales, quienes nunca han escondido sus ambiciones personales. |

|

|

|

|

The Mexico Solidarity Project brings together activists from various socialist and left organizations and individuals committed to worker and global justice. We see the 2018 election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as president of Mexico as a watershed moment. AMLO and his progressive Morena party aim to end generations of corruption, impoverishment, and subservience to US interests. Our Project supports not just Morena, but all Mexicans struggling for basic rights, and opposes US efforts to undermine organizing and Mexico’s national sovereignty.

Editorial committee: Meizhu Lui, Bruce Hobson, Agatha Hinman, Victoria Hamlin, Courtney Childs, Pedro Gellert. To give feedback or get involved yourself, please email us! |

|

Subscribe! Get the Mexico Solidarity Bulletin in your email box every week. |

|

Web page and application support for the Mexico Solidarity Project from NOVA Web Development, a democratically run, worker-owned and operated cooperative focused on developing free software tools for progressive organizations. |