|

|

The weekly newsletter of the Mexico Solidarity Project |

|

Every issue archived online at mexicosolidarityproject.org |

|

October 09, 2024 |

|

|

|

Farewell AMLO! The End of the Beginning |

|

Meizhu Lui, for the editorial team |

|

|

Farewell AMLO! The End of the Beginning: Photo by Carl deSouza/AFP via Getty Images |

|

I must admit that I got teary-eyed and starry-eyed watching AMLO give his final El Grito, or battle cry, to defend Mexico’s independence and to honor its revolutionary heroes. From the palace balcony, he spoke to an enormous multitude of teary-eyed and starry-eyed citizens packed below in the zocalo. When he finished the traditional ringing of the bell and waving of the flag, he and his wife stood watching the fireworks display. Seeing them from behind in the video, framed by curtains, I wouldn’t have been surprised if they had flown off the balcony up to the moon!

AMLO’s six years will go down in history as a true “4th transformation,” a peaceful but decisive revolution that started a process of turning upside down Mexico’s social and economic pyramid. Because this transitional moment is so noteworthy, our interview this week is longer than usual. And who better than Edwin Ackerman to explain AMLO’s unprecedented accomplishments?

Over the last few years, we’ve interviewed activists who were not always happy with AMLO — feminists, families of the disappeared, independent labor organizers, Zapatistas. Their criticisms have basis in fact. AMLO had his shortcomings; he’s human — he can’t fly to the moon. He inherited a government with corruption baked in, and he had only six years to dismantle some of the structures that enabled it.

Now the responsibility falls to Claudia Sheinbaum. AMLO laid the foundation; she promises to build “the second floor.” And as AMLO says farewell, the Mexican people will shout his name, a well earned honor among the national heroes celebrated in El Grito.

Viva AMLO! Viva Mexico! |

|

For a deeper dive into current news and analysis in English, check out our media website. And definitely see the new English podcast ¡Soberanía! (Sovereignty) with José Luis Granados Ceja and Kurt Hackbarth. They entertain, while dismantling the lies and distortions about Mexico fed to us by the mainstream media. |

|

Don’t miss an issue! Sign up for a free Mexico Solidarity Bulletin subscription. |

|

|

Mexico Rising: Under AMLO, a Sharp Left Turn |

|

Tijuana born and raised, Edwin F. Ackerman is a historian who studies how political identities and parties are formed and how they work. Jacobin magazine, NPR, Democracy Now, and other media outlets have sought his expertise. Now at the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs at Syracuse University, he’s the author of Origins of the Mass Party: Dispossession and the Party-Form in Mexico and Bolivia. This analysis is expanded in his recent Catalyst article. |

|

|

AMLO leaves office with an approval rating of almost 80%, and his successor and his party trounced the neoliberal opposition. What did AMLO want to achieve during his presidency?

AMLO envisioned his 2018 victory less as a change in government than as a transformative regime change. As he exits the political stage, is Morena’s growing electoral success due to the emergence of an entirely new social contract? Can the left consolidate the Fourth Transformation?

AMLO’s rise must be put in the context of the Mexican left’s trajectory during the neoliberal era. I want to make three broad points. The first is that the distinctive feature of AMLO’s project is how he reframed anti-corruption politics in a progressive direction. Second, he premised his actual policies and actions on a diagnosis of corruption as a specific neoliberal political economy — not as a series of isolated scandals or moral failings but a particular logic of capital accumulation that needed to be addressed as a system. Third, AMLO’s tenure is better understood as post-neoliberal rather than as a complete break from neoliberal policies — global free trade, for example — which are irreversible. He aimed to reshape the relationship between state and market in a society already deeply changed by decades of neoliberalism. What were the failures of the electoral left during the neoliberal period, from the 1980’s to AMLO’s election in 2018?

AMLO’s administration is a late example of the “pink tide” governments that swept South America beginning in the early 2000s but had never reached Mexico. What was unique about Mexico that explains this?

The PRI ruled Mexico without interruption from 1929 to 2000. It didn’t maintain power only through fraud and repression. It also created a dense network of corporatist and clientelist relations, enabling it to co-opt emerging grassroots worker and peasant leaders. In other words, the sectors theoretically most prone to oppositional left-leaning mobilization were already organized under the PRI.

A Mexican Marxist thinker, José Revueltas, once explained that the PRI "can penetrate its organizational filaments all the way to the deepest layers of the population and thus impede the development of class politics.” As a consequence, Mexico’s left developed without a social base and without a coherent program. |

|

|

AMLO running for governor of Tabasco, 1988. Photo: especial. |

|

The Left’s stunted development is perhaps best captured by AMLO’s own trajectory. His political path is entirely peculiar to twentieth-century Mexico. He doesn’t come from the socialist or social democratic left like his European counterparts. And he doesn’t come from militant union activism like Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva or Evo Morales in South America. |

|

López Obrador was a PRI member and political appointee early in his career, when the party — the heir, after all, to an early twentieth-century agrarian revolution — still contained a strong progressive nationalist wing. |

|

|

AMLO campaigning with PRD’s Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, 1996: Photo: Arena Public |

|

The PRI’s hard turn toward neoliberalism in the 1980s left the party’s nationalist wing isolated, eventually provoking a full break; those who left, including AMLO, then formed the center-left PRD party.

The PRI presided over a mixed state-market (public-private) economy. As the party consolidated power through corporatist arrangements, state enterprises and union leadership became synonymous with waste, mismanagement and corruption. Then in the 80s and 90s, the PAN party advocated for fighting corruption through dismantling public entities like the national oil company Pemex and opening up the economy to privatization and market competition. Those ideas propelled PAN to electoral victory between 2000 and 2012.

The PRD had limited electoral success; the most significant win was AMLO’s election as the mayor (governor) of Mexico City. When the PRD shifted right, collaborating with President Enrique Peña Nieto on major neoliberal reforms, AMLO left the PRD. He then led Morena, a coalition of social movements, to register as a political party In 2014.

So the Mexican people finally rejected the PRI in 2000 due to their disgust with state corruption; the private market seemed to be the answer. How did AMLO change the way that corruption was viewed?

PRI president Peña Nieto left office with the lowest approval rating on record — 24 percent. This dismal figure reflected, among other things, the widespread discontent stemming from a series of high-profile corruption scandals that came to define his administration. Anti-corruption became the principal component of AMLO’s campaign and of his economic program. His campaign focused on three issues: ending corruption, regaining peace and using the state as an engine for redistributive economic policies. He saw these issues as fundamentally connected: corruption crippled the state’s capacity to energize the economy, and the growth of organized crime was a consequence of the abandonment of the redistributive role of the state.

Central to this understanding was his claim that neoliberalism was defined by corruption. As he put it in his inaugural speech, “I insist that the hallmark of neoliberalism is corruption. It sounds harsh, but privatization in Mexico has been synonymous with corruption. Political power and economic power have mutually fed and nurtured each other, and the theft of the people’s goods and the nation’s wealth has been established as the modus operandi.”

This view contrasts with the PRI/PAN neoliberal view, in which corruption was seen as synonymous with the large role of the public sector in the nation’s economy and the misdeeds of some bad actors there. But for López Obrador, corruption is not merely a series of individual crimes or isolated scandals; it is a consequence of the reconfiguration of the state-market relationship over the past decades. Corruption had become integral to a regime of private accumulation facilitated by the state.

Government officials siphoned off public funds through various mechanisms ranging from the outsourcing of government functions to the creation of parallel shell companies. A prime example was the sale of Telmex in 1990 to corporate magnate Carlos Slim, a close associate of then president Salinas de Gortari. These sorts of transactions turned state-owned entities into privately owned corporations, giving rise to an ultra-wealthy class.

Under the 2000 to 2012 PAN governments, even more boondoggle projects proliferated. |

|

The independence bicentennial celebrations during Calderón’s administration are a notable example. The Estela de Luz, a hundred-meter-tall quartz monument, was inaugurated over a year late and cost three times its initial budget. A federal audit revealed overpriced construction materials and other irregularities. |

|

|

The Estela de Luz, “This is the obituary of the victims of corruption.” Photo: Regeneración, August 2023. |

|

AMLO’s linking of corruption and neoliberalism suggested that a solution required more than redesigning public institutions; it required reversing the state-market equation — in favor of the state. It is quite telling that AMLO’s cancellation of the Texcoco Airport project Peña Nieto had started differed from previous anti-corruption cases, in that it targeted a project symbolizing the systematic, large-scale transfer of public resources to private contractors.

So did AMLO replace neoliberalism with a new economic system?

A few months into his term, AMLO announced, “The neoliberal model, with its policies against the people, of stealing and giving away (public resources), is hereby abolished.” But in my view, the transition away from neoliberalism under AMLO — while significant — is moderate. His policies can best be described as “post-neoliberal.” That is, his reforms took place within neoliberalism, and they simply began to weaken or transform key tenets of neoliberal thought and politics. He began a process rather than instituting a new economic system. |

|

|

AMLO sold the presidential jet and instead drives a VW Jetta. Photo: Polemon, Jorge Gomez Laredo |

|

AMLO reshaped the relationship between state and market in several ways. The flagship concept of AMLO’s government is “republican austerity” — a strategic adoption of neoliberal language used to combat neoliberalism itself. |

|

This meant dismantling many private intermediaries between the state and the citizenry. Middlemen companies, NGOs, trusts (fideicomisos) and so on were awarded state contracts to deliver public services. AMLO saw these entities as opaque, redundant, expensive — bottlenecks for clawing back public dollars meant to be spent for the good of the people. AMLO’s government also rejected privatization efforts. State-led infrastructure mega-projects like the Felipe Ángeles Airport, the Dos Bocas refinery, the Maya Train, a massive reforestation program, and more mark a break from PRI/PAN projects, which were often unnecessary and left unfinished. AMLO’s projects emphasize the importance of generating public-works jobs and economic development that strengthens local communities rather than displacing them.

AMLO’s administration has moved decisively to bolster the public sector’s relative power, particularly in the energy industry. It has increased tax collection from the wealthiest citizens by more than 200 percent. Conglomerates like Grupo Modelo, Elektra, Walmart and billionaire Carlos Slim’s companies are now under pressure to fulfill their tax obligations. The Financial Times described Raquel Buenrostro, then economic secretary, as an “iron lady” cracking a “whip on multinationals’ taxes.” These efforts yielded the financial means to expand the social benefit programs for Mexico’s people, “and first, the poor,” without raising taxes, which would risk alienating Mexico’s still important business sector.

Has AMLO set the stage for the growth of a new left based in the working class?

Working-class advances over the past six years have been startling. Real wages have surged by approximately 30 percent. The earnings of the bottom 10 percent of income earners have soared by 98.8 percent. Inequality has decreased. Over five million people were lifted out of poverty — the largest reduction in twenty-two years. But a rising standard of living alone is not enough to build a left.

AMLO restored the language of class in the political arena. His pride in his own modest rural background far from the urban elite and his jabs at fifis during his morning conferences contributed to his popularity. Among other things, it caused the electorate to become increasingly polarized along clear class lines. In the 2018 election, working-class support was dispersed across various parties, including those in the neoliberal bloc, while AMLO had significant support from middle-class professionals. But then, while in 2018, 48 percent of college-educated voters supported Morena’s congressional candidates, only 33 percent did in 2021. Conversely, support from voters with only elementary education rose from 42 percent in 2018 to 55 percent in 2021.

The loss of middle-class people’s support for AMLO is partly due to their symbolic demotion in his narrative. |

|

While previous administrations valued cabinets of experts trained at elite universities, AMLO criticizes such technocratic expertise as political marketing and instead praises administrators for their closeness to the people. |

|

|

AMLO, beloved by the people. Edgar Negrete Lira / Cuartoscuro.com |

|

Unlike AMLO, Claudia Sheinbaum is of the left. Compared to her, AMLO said, he’s bourgeois! What are the challenges to the left in power?

The neoliberal period in Mexico, as elsewhere, caused the growth of the informal sector, now between 40 to 60 percent of the Mexican workforce, and also increased its precarity. This has hampered the working classes from generating their own demands and elevating them to the political sphere, leading to a shortage of organized pressure from below to push the government leftward.

AMLO’s administration took over after a prolonged period of hollowing out the state, which impaired the actual implementation of new government plans. Without fully functioning governmental departments and public servants with sufficient experience and expertise, without state capacity, we can expect continued dependence on public-private partnerships and reliance on the military’s administrative apparatus to build and operate many infrastructure projects.

What are the dilemmas inherent in transitioning away from neoliberalism? Some include attempting to revive a welfare state with a deteriorated administrative apparatus, the contradictions of neo-developmentalist projects amid the looming climate crisis, the complexities of implementing progressive taxation during periods of stagnant growth, and the challenges of shifting away from a foreign investment–driven growth model. Consequently, the left’s story in twenty-first-century Mexico holds broad relevance, as these structural contradictions mirror the dilemmas the contemporary left worldwide faces. |

|

|

|

|

Crazy Opulence |

|

|

Activist Vicky Hamlin, a retired tradeswoman, shop steward, and painter, shines the light — in her art and in this column — on the lives of working people and the world they live in. |

|

|

What to do with disposable income? Buy art! For love, social standing, investment, money laundering, fraud, show-off and bragging rights? Yup, all of the above. |

|

Growing up in New York City, I remember when they took old abandoned warehouses and converted them into artist's live/work spaces. Those old derelict skid row buildings are now multi-million dollar real estate holdings. |

|

|

The Starving Artist's Survival Guide, Laurie Lindop, Gallery Books, 2005 |

|

|

Bushwick Avenue in Brooklyn, 2017: Peter Moskowitz, What Role Do Artists Play in Gentrification?, Artsy |

|

Why is it that starving artists, those poor, working-for-love, creative, dedicated people, are so often the front line for real estate speculation? They are in the bizarre place of converting “nothing” into “something” — creativity into cash profit. It’s so crazy that poor, starving artists pave the way for gentrification. |

|

The art of Mexico has included folk art, ancient art and revolutionary art, springing from people’s movements, centuries-long history and game-changing revolution. |

|

|

The Poor, Starving Artist, Saatchi Art |

|

|

Spanish colonial school, Mexico, 17th century. Lady portrait. |

|

Art in Mexico has also reflected private wealth, as in the European-style portraits of the 17th, 18th, 19th and 20th centuries, but these private art collections are very different than public art spaces. |

|

|

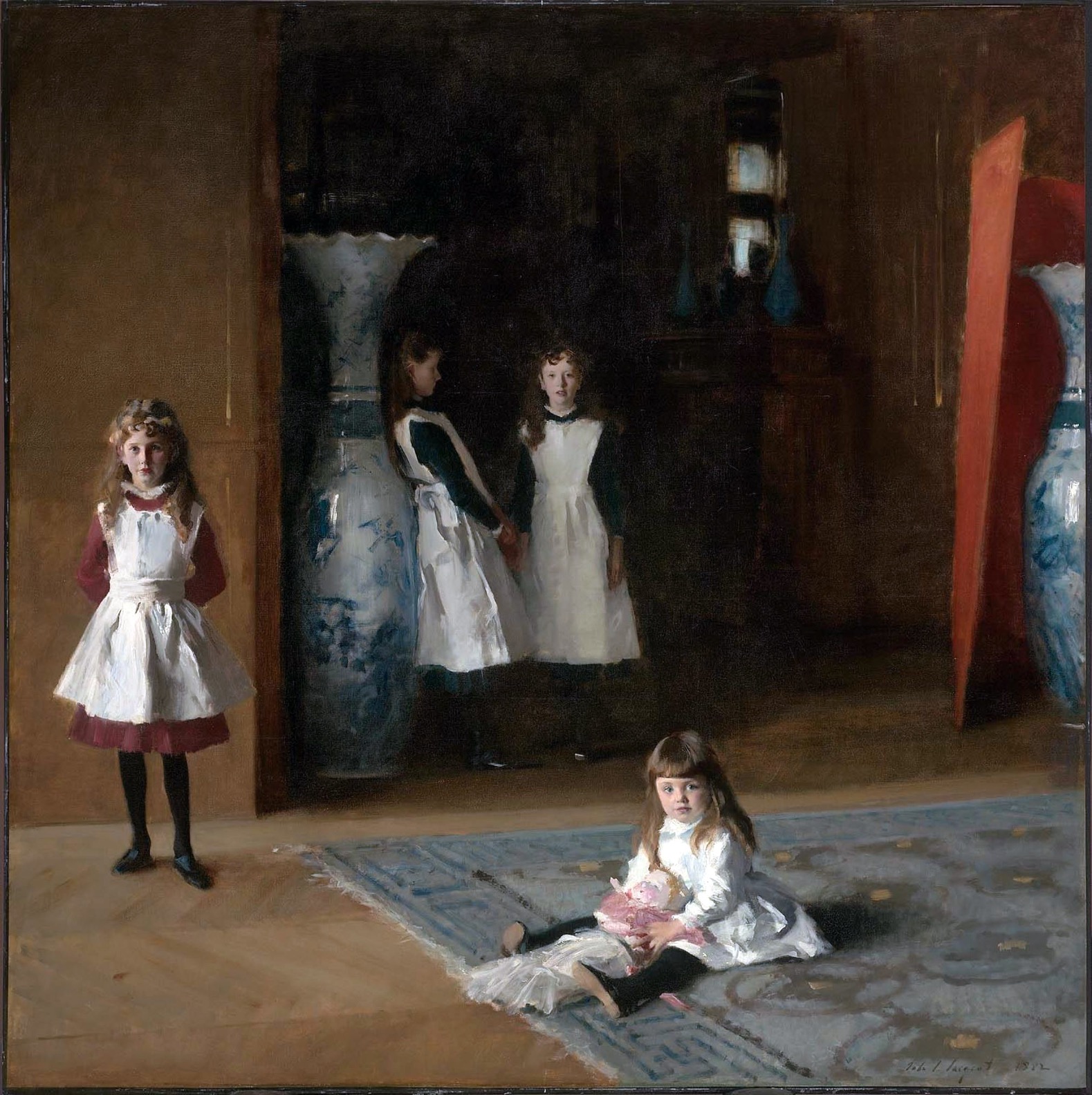

John Singer Sargent, The Daughters of Edward Darley Bolt, 1882 |

|

For European rich people’s art collections, there had to exist the over-the-top wealth that produces John Singer Sargent and Rembrandt, artists who understood the crazy-rich people they were painting and had the serious chops to reflect them and their position in the social hierarchy. |

|

The huge, oh-so-wonderful (public) National Anthropology Museum in Mexico City is world-class. It reflects a different kind of social wealth than, say, the Frick museum (private collection; old Master paintings, European sculpture and decorative arts) in New York City. The role of wealth in art, and art in wealth, is complicated. Enter Carlos Slim.

Who?

Here is what Wikipedia says —

“Carlos Slim Helú is a Mexican business magnate, investor, and philanthropist. From 2010 to 2013, Slim was ranked as the richest person in the world by Forbes business magazine. He derived his fortune from his extensive holdings in a considerable number of Mexican companies through his conglomerate, Grupo Carso.”

And —

“Established in 1986, Fundación Carlos Slim sponsors the Museo Soumaya in Mexico City, opened in 2011. It holds 66,000 pieces . . . . |

|

I visited Museo Soumaya recently, which holds Slim’s private collection. Most everything in it is about opulence, bling, but it is kind of wonderful. It houses a notable, diverse collection of contemporary art, lots of which is interesting, important, fascinating work. |

|

|

Museo Soumaya. Photo: Vicky Hamlin |

|

The older 15th to 20th century painting and sculpture collections are important in another way. They also have historical documents, gold and silver, harpsichords, collections of typewriters, old machinery, glass, coins, religious relics.

All good. Rich people do some things extraordinarily well. Like education, food, and, yes, some kinds of art. But money changes everything. Artists tailor their work to suit “the market,” and those collections become museums, now worth a fortune. And the wheels of capitalist accumulation go round and round . . . . |

|

|

|

|

Recent news reports and commentaries, from progressive and mainstream media, |

|

Kurt Hackbarth, Claudia Sheinbaum, Presidenta Jacobin. As she has often stated, [Sheinbaum] did not attain to the presidency alone, and the movement that guaranteed MORENA its second term will need to remain in constant mobilization.

Kurt Hackbarth, Claudia Sheinbaum, presidenta Jacobin Latin America. La primera mujer presidenta de México, Claudia Sheinbaum, tomó posesión de su cargo esta semana, sucediendo a AMLO tras una aplastante victoria electoral. Es de esperar que la derecha redoble sus ataques mediáticos y encuentre un cómplice dispuesto en Estados Unidos.

Claudia Sheinbaum Swears as the New President of Mexico Telesur English. With the band on her right shoulder, the new president of Mexico delivered a message to the people and began by thanking her successor, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, as well as remembering the martyrs who succeed him and inspire the program that her government carried out.

Sandra Hernández García y Rocío González Alvarado, Asume Clara Brugada el Gobierno de la CDMX La Jornada. En su primer discurso como jefa de Gobierno de la Ciudad de México, Clara Brugada Molina afirmó que el segundo piso de la transformación implica la revolución de las mujeres para que se liberen como responsables de los cuidados, lo que consideró esclavitud moderna.

Alejandra Garcia, Claudia Sheinbaum: I Will Rule for All Mexicans Resumen Latinoamericano. Everyone wants to see with their own eyes the woman who is ushering in a new era for Mexico.

Viri Ríos, Airbnb debe regularse más Milenio. Regular a Airbnb es positivo porque su presencia incrementa los precios de las rentas al reducir la cantidad de viviendas que están disponibles para rentas largas. Tener un Airbnb poco regulado, como aparentemente desea el PAN, solo beneficia a la gente más rica que posee más de una propiedad.

Atilio Boron, Mexico: a New Turn for the Left Resumen Latinoamericano. The powerful could not do away with AMLO, who took away many of their privileges and began to put an end to the plunder they had exercised for more than a century. Nor will they be able to with Claudia Sheinbaum.

Alonso Urrutia y Emir Olivares, Sheinbaum envía al Senado regulaciones para elegir a los jueces La Jornada. En conferencia declaró que en esta iniciativa considera opciones en aquellos aspectos en que la reforma constitucional asignó responsabilidades al Poder Judicial en la organización de los comicios si se incumplen.

Justin Rohlrich, DEA ignored waterboarding, torture by Latin American police partners, says watchdog The Independent. The notorious US Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA), which has been waging a very public battle with the Mexican government and been plagued with corruption at its highest levels, has mostly escaped scrutiny by the press in its home country.

Sugeyry Romina Gándara, Un agujero ingobernable Sin Embargo. Nadie en Chilpancingo se salva de los arraigados criminales. Ni las autoridades |

|

|

|

|

The Mexico Solidarity Project brings together activists from various socialist and left organizations and individuals committed to worker and global justice. We see the 2018 election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as president of Mexico as a watershed moment. AMLO and his progressive Morena party aim to end generations of corruption, impoverishment, and subservience to US interests. Our Project supports not just Morena, but all Mexicans struggling for basic rights, and opposes US efforts to undermine organizing and Mexico’s national sovereignty.

Editorial committee: Meizhu Lui, Bruce Hobson, Agatha Hinman, Victoria Hamlin, Courtney Childs. To give feedback or get involved yourself, please email us! |

|

Subscribe! Get the Mexico Solidarity Bulletin in your email box every week. |

|

Web page and application support for the Mexico Solidarity Project from NOVA Web Development, a democratically run, worker-owned and operated cooperative focused on developing free software tools for progressive organizations. |