|

|

The weekly newsletter of the Mexico Solidarity Project |

|

Every issue archived online at mexicosolidarityproject.org/archives/ |

|

December 17, 2025 |

|

|

|

Friends, It's time for our annual two week holiday break. The next edition will hit your email boxes on Wednesday, January 7, 2026. We hope you too find peace, joy, and respite during this holiday season! |

|

|

|

Gifts, Christmas and Otherwise |

|

Meizhu Lui, for the editorial team |

|

|

Migrants help each other cross the Darien Gap: Photo: Keiber Bastidas: Doctors Without Borders |

|

Three magi, three wise men, found baby Jesus, born in a feeding trough for livestock. They brought gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh. If they were three wise women, they might have brought more useful gifts, like diapers or a warm baby bunting.

But they did accomplish something as important as many of Jesus’s own teachings. They were an example that has lasted thousands of years — that giving freely without conditions or wanting recognition is its own reward.

Today, as we contemplate the lessons and traditions of Christmas, we bring you the story of Dales Louissaint, a Haitian migrant who made a dangerous journey across nine countries before arriving in Mexico. Along the way, he encountered greedy people, people willing to cheat a migrant out of their last dollar.

But in Mexico, he met many who gave him gifts — not frivolous or inappropriate ones — but exactly what he needed to follow his dream of becoming an immigration lawyer. A place to stay. A job. Spanish language lessons in the evenings after work. A promotion. The extraordinary gift of tuition to the university. Their only reward was watching Dales succeed, step by step.

Already, Dales is repaying them by paying it forward, helping other migrants — for free — who need a compassionate counselor who has shared their experiences, speaks their language and has their best interests at heart.

In these days when we need peace and love more than ever, ordinary people — like the ones who gave Dales gifts without being asked and without asking for anything in return — are our world’s saviors, they are today’s magi. |

|

|

Hell and High Water: from Haiti to Mexico |

|

Dales Louissant was studying law in his native Haiti before he had to suddenly migrate to Mexico in 2014. In spite of formidable obstacles, he was able to complete his law degree at the Autonomous University of Baja California in Tijuana. He worked for the Human Rights Commission of Baja California, for the US Committee for Refugees and Immigrants and for the UN Refugee Agency. He is now getting a master’s degree in law at the University of San Diego in the US. |

|

|

How old were you when you left Haiti? Was it a hard decision to leave your home?

I was 23, going to law school and helping my father on his farm. Relatives had migrated to Brazil and Guyana and were sending me money to support my education. But in 2016, they gave me an ultimatum: stay or go. It was hard to leave school, because becoming a lawyer was my dream. But the economic situation and the violence in Haiti made me choose to leave home.

You traveled one of the most dangerous routes through the Darien Gap to Mexico. People die on that trip! |

|

|

Britanica map of Central and South America |

|

That’s true. First, my sister flew me to Brazil, and from there, I headed north to the US. I crossed into Peru, undocumented, and used bribes to get through the country, including bribing police. Drivers purposely got me lost to increase their price. I spent four bad days on a bus, sick from the food.

More bribes to get through Ecuador. Then Colombia — and it got worse. |

|

After nine days on buses, my fellow migrants and I had to cross a body of water by boat. I was terrified! The boat was for 20 people, but they packed 40 of us into it. I prayed, “If I don’t die in the water, nothing can kill me!”

We survived and next had to go on foot across the Darien Gap, a mountainous, roadless jungle, about 60 miles long, often deadly for migrants. Here, we left most of our belongings behind, having to choose: do I take water — or clothes? We walked all day but not at night; we had no lights. Our guide? He took us a short way and told us we were on our own. We got lost over and over. We had a two-month-old baby in our group. We wondered, “Will we make it?” |

|

|

A Haitian mother and her child on the Darien Gap: Photo: Raul Arboleda via Getty Images |

|

At the middle of the Darien Gap, the border between Colombia and Panama, the Panamanian police stopped us. Panama didn’t accept too many migrants arriving at once, so they detained us, without ever saying for how long. It was for 12 days with rice our only food. I don’t know how — I believe with the help of God — but even in the rain, we made a fire to cook it. We had only the clothes on our backs. We drank water from the river. But after surviving that boat ride, I had faith that I had God’s protection. I wasn’t afraid. |

|

|

The Darién Gap, which hundreds of people cross every day: Photo: Federico Rios |

|

Arriving in Panama, I could finally contact my family, who thought I was dead, because it shouldn’t take so long to walk there from Colombia! I spent two months in police custody, in a shelter. The police took 10% of any money I received from my family. |

|

In Costa Rica, no police bothered us, and I even stayed in a hotel. From there, we paid a coyote to get us across Nicaragua, and in Honduras, we paid again. We traveled through Guatemala and into Tapachula in Chiapas, Mexico.

I’d been traveling for four months. |

|

|

‘Welcome to Costa Rica’, Peñas Blancas, Guanacaste, Costa Rica: Photh: Ezequiel Becerra/AFP/Getty Images |

|

We surrendered ourselves to the Mexican officials; we got papers good for 22 days to travel across Mexico. I met a cousin in Tapachula, also migrating, and we traveled together. We knew people in the US, our hoped-for destination.

But I changed my plans — it was 2016, Trump was now president, and the US wasn’t good for migrants. I decided instead to stay in Tijuana.

Once in Mexico, as a Haitian migrant, a Black man, did you face discrimination?

Many Mexicans are scared of Haitians, and sometimes someone yelled, “Go home! Get out of the country!” But in Tijuana, the Mexican people supported me, especially the churches. I stayed in a church shelter in Rosalito, and we Haitians were allowed to cook our own food, which is important to us.

How did you manage to go from a refugee camp to law school?!

After four months, I said, “I need to get moving!” I told everyone I met that I dreamed of going to the university and getting a law degree. But I spoke no Spanish, and I’d told my family not to support me anymore. I got a job in construction, and the owner was very kind. He told me his son was going to a public university in Tijuana. Getting into that university became my goal. His son taught me Spanish every day, a wonderful gift that helped me prepare. I never took a Spanish class; people I met gave me lessons for free. |

|

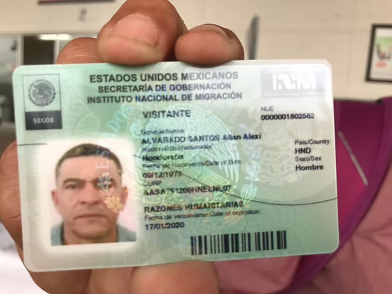

At the International Center, I got a “humanitarian visa,” which you can get just for being a migrant — you don’t have to prove anything like you do for asylum. The application wasn’t hard to fill out, and I started helping other Haitians get the visa, so they didn’t have to go to the Center or pay a fee.

Then I got a job at a big company that sold and installed stone products — 300 of us were Haitians. |

|

|

Humanitarian visa from Chiapas. |

|

I, too, did manual work, and it was hard! But the managers noticed that I was helping other Haitians with problems, and, in 2018, they offered me a job in human resources. In that role, I convinced the company to give Haitians work permits, not humanitarian visas, which have to be renewed yearly. Work permits are good for four years; then you can apply for permanent residency. Haitians don’t want charity; we want documents! Haitians are now respected in Tijuana because employers know “they came to work.” |

|

With better Spanish, I applied to the Autonomous University of Baja California in Tijuana and got accepted to law school in 2019. A friend introduced me to Adrian Melendez, who had started a program called Habesha that paid the tuition for Syrian migrants to get university degrees. He helped me with tuition too! I worked from 4:00 AM to 2:30 PM, went to school at 4:00 PM, and got to bed at midnight. How could I keep that up?

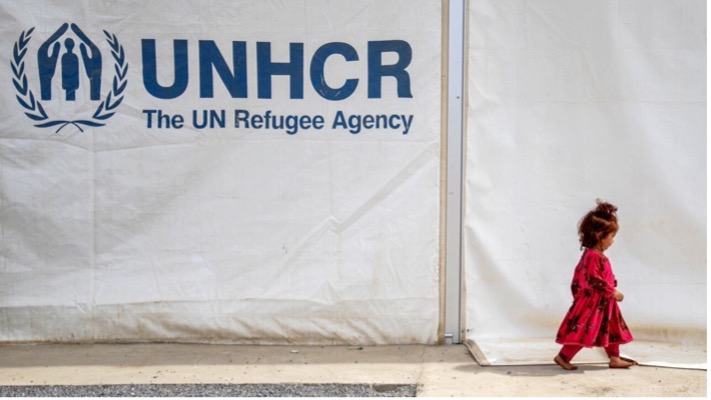

Adrian took a job with USCRI, which is the US Committee for Refugees and Immigrants. He helped me again, by hiring me part-time, so I could leave the stone company. Right after that, the Human Rights Commission of Baja California offered me a job — I was the first Haitian to work for them. I finished my law degree and got a job at the UN Refugee Agency. Because of the people I met in Mexico, I achieved the dream I’d had since living in Haiti. |

|

|

the UN Refugee Agency |

|

My next goal was a master’s degree, with a specialty in international migration; the University of San Diego has a good program and is close to my home in Tijuana. That’s where I am today. Now, I dream of becoming an immigration lawyer based in the US. In Mexico, help for migrants is free, but not in the US — poor migrants there need my help.

God sent good people into my life. At every step of the way, their unexpected gifts, asking nothing of me in return, enabled me to move ahead. I am blessed. |

|

|

|

|

Rogue States and Pirates |

|

|

Mexico City based freelance writer and photojournalist José Luis Granados Ceja previously spent time as a staff writer for teleSUR, and currently works with Venezuelanalysis. His writing on contemporary Latin American democratic struggles can be followed on X (Twitter): @GranadosCeja. |

|

|

There is no longer any room for interpretation. Recent events have confirmed, beyond doubt, that the United States intends to dominate Latin America and the Caribbean and to crush opposition, even by using military means.

Honduras offers a clear example. Days before the November 30 vote, US President Trump’s flagrant intervention indisputably altered the outcome, leaving the election unresolved weeks later. My colleague Kurt Hackbarth aptly coined the term “preemptive fraud.”

"The method?” writes Hackbarth. “Blackmailing voters at their weakest points — debt, migration, violence — to force the desired electoral outcome. Cleaner, without the need to get one's hands dirty with ballot stuffers, armies or clandestine operations.”

Given its success in Honduras and Argentina and the lack of any serious regional or institutional pushback, rest assured that, moving forward, Washington will deploy this tactic widely.

The best way to inoculate a population against Washington’s latest method of deception is through deep, widespread political consciousness — so that the people will recognize attempts to deny their right to choose their own destiny and reject those attempts forthright.

But even a conscious and mobilized population doesn’t guarantee a country’s sovereignty. US imperialism has repeatedly shown that it won’t tolerate counter-hegemonic governments winning at the ballot box, which brings us to Venezuela.

For decades, the US has sought to oust Venezuela’s leftist Bolivarian Revolution, using every tactic in the playbook — from coups, illegal sanctions, and now to outright piracy on the high seas. This week, the US seized an oil tanker off Venezuela’s coast carrying roughly $78 million in crude oil, a wanton act of piracy. Furthermore, Trump threatened to impose a de facto US Navy-backed oil blockade on Venezuela.

Make no mistake, a blockade not sanctioned by the UN Security Council or imposed outside an armed conflict is illegal under international law, as are the executions through drone strikes on small boats carried out by the US. Washington openly flouts international law, aided by US media efforts to manufacture consent through barefaced lies, claiming that unilateral US coercive measures constitute “international sanctions.”

A US naval blockade on Venezuela would constitute collective punishment, another crime against humanity. Venezuelan economist Francisco Rodríguez warns a blockade would trigger another massive economic crisis. Venezuela already has to jump through US-imposed hurdles to sell its most important export, oil. Following Wednesday’s seizure, Asian buyers are demanding deeper discounts on Venezuelan crude. By cutting off oil revenues, Trump is increasing pressure to remove elected President Nicolás Maduro from office.

Washington loves to label countries that defy it as “rogue states,” but the country posing a threat to its neighbors is the United States — and the danger is rising. The National Security Strategy for 2025, published earlier this month, confirms a renewed US focus on the so-called Western Hemisphere, aimed at rebuilding US capacity to contest global hegemony amid its rivalry with China. Read in tandem with the “Trump Corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine, the strategy represents a massive threat to the sovereignty of Latin American and Caribbean countries.

The US, this "rogue state,” has used every possible means to interfere in the internal affairs of Latin American countries and now threatens direct land invasions. Yet, the region remains woefully unprepared. Time is running out to forge a coherent regional response to the threat the US poses to all. |

|

|

|

Recent news reports and commentaries, from progressive and mainstream media, |

|

David Raby, Sheinbaum turns the tide: mass mobilisation and reform drive Mexico’s Transformation forward Morning Star. Ten days after right-wing destabilisation attempts, Mexico’s leadership has emerged strengthened, securing historic labour and wage agreements, while opposition-backed protests have crumbled under scrutiny.

La Dua: cuando México es más mercancía que cultura El Machete. Eventos promocionales, lanzamientos, colaboraciones, pop-ups gastronómicos: todos se concentran en las mismas cuatro colonias —Roma, Condesa, Juárez y Polanco— como si la ciudad terminara donde terminan los murales fotogénicos y los departamentos remodelados para Airbnb.

México y EE.UU. alcanzan acuerdo sobre reparto de agua y evitan aranceles anunciados por Trump Telesur. Con el acuerdo se cumplirá el Tratado de Aguas 1944 y evitará arancel del 5% anunciado por Trump. Jorge Barrera, Next year's Mexico trade mission may be biggest ever launched by Canada CBC News. Prime Minister Mark Carney and Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum in regular contact, says ambassador.

Anahí Del Ángel, Plaguicidas provocan muerte masiva de abejas en 15 entidades Revista Contralínea. Esta crisis ya provocó la pérdida de casi 300 mil colonias entre 2013 y 2024.

China urges Mexico to promptly correct unilateralist, protectionist tariff measure; initiates trade, investment barrier probe Global Times. To safeguard the interests of relevant Chinese industries, the MOFCOM initiated a trade and investment barrier investigation against Mexico in accordance with the law at the end of September, and the investigation is ongoing.

Obed Rosas, Maestro forzado a las armas, Lucio Cabañas ha cobrado nueva dimensión Sin Embargo. Su movimiento, de base campesina, buscó "derrocar a los ricos y formar un gobierno de campesinos y obreros," lo que provocó una brutal represión militar por parte del gobierno mexicano.

Water Dispute Resolution Prevents Higher U.S. Tariffs on Mexican Exports Telesur. A last-minute agreement over shared water rights has averted a 5% tariff on Mexican exports to the United States, with Mexico committing to release nearly 250 million cubic meters of water under the 1944 treaty.

Mario Patrón, Derechos humanos cuesta arriba La Jornada. Claros avances en derechos laborales y económicos contrastan notablemente con los retrocesos y contradicciones que se observan en otros ámbitos. |

|

|

|

|

The Mexico Solidarity Project brings together activists from various socialist and left organizations and individuals committed to worker and global justice. We see the 2018 election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as president of Mexico as a watershed moment. AMLO and his progressive Morena party aim to end generations of corruption, impoverishment, and subservience to US interests. Our Project supports not just Morena, but all Mexicans struggling for basic rights, and opposes US efforts to undermine organizing and Mexico’s national sovereignty.

Editorial committee: Meizhu Lui, Bruce Hobson, Agatha Hinman, Victoria Hamlin, Courtney Childs, Pedro Gellert. To give feedback or get involved yourself, please email us! |

|

Subscribe! Get the Mexico Solidarity Bulletin in your email box every week. |

|

Web page and application support for the Mexico Solidarity Project from NOVA Web Development, a democratically run, worker-owned and operated cooperative focused on developing free software tools for progressive organizations. |