|

|

The weekly newsletter of the Mexico Solidarity Project |

|

Every issue archived online at mexicosolidarityproject.org |

|

December 04, 2024 |

|

|

|

Improving Health for and with Disabled People |

|

Bruce Hobson, for the editorial team |

|

|

|

In today’s world, 16% of the human population — 1.3 billion people — have some form of physical disability. In Global South countries, the numbers are proportionately higher. Overwhelmingly, it is parents, grandparents and other children who care for disabled children, whose most common disabilities are cerebral palsy, polio, and spinal cord injury. Given the poverty stemming from the unfair distribution of wealth and the indifference of government officials to the concerns of poor and disabled people, they and their families face enormous obstacles to getting health or rehabilitation services.

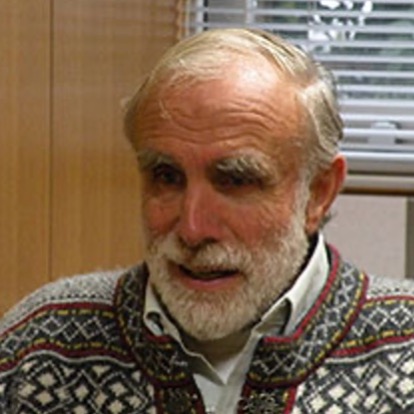

Since the mid-sixties, North American David Werner has lived in the Sierra Madre of Mexico, bringing health care to rural areas where none existed. In 1979, he co-founded the rural rehabilitation program, Project PROJIMO, which was eventually run and directed by disabled health workers. He himself has an uncommon congenital disability, Marie-Charcot-Tooth.

David Werner was my high school teacher, and together we traveled to rural Mexico, where I saw the lack of health care for myself. In 1985, I was working as a carpenter at the UCLA medical center when David called me with a request — the PROJIMO rehab team had asked if I’d come to Ajoya to teach basic carpentry skills and build a children’s toy shop. UCLA knew I supported rural Mexican health projects and insisted I go for six months and, on my return, give presentations about my experiences to medical students and hospital staff. Two weeks later, I headed south — but I never returned to UCLA.

I’d traveled in rural Mexico many times since I was young, but Ajoya was another world. In my first month at Project PROJIMO, the co-director Mari Picos recruited me to work with her. She taught me about the special needs of those with spinal cord injury (she herself was paraplegic). I learned how to treat deep pressure sores, to use Foley and condom catheters, to keep people hydrated and to help them maintain regular bowels.

My love for the mountains of the Sierra Madre and my connection with the mountain people — disabled and able-bodied — remains today.

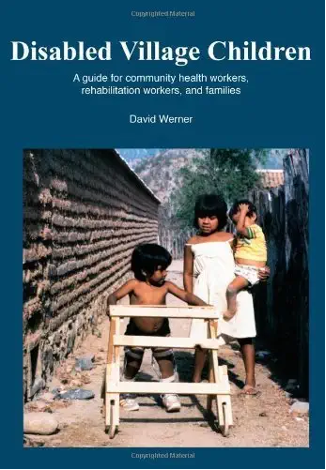

In our previous interview with David (September 11, 2024), we highlighted his world-renowned book Where There Is No Doctor. In this Bulletin, David talks about community-based rehabilitation programs in Africa, Asia, Latin America and many Pacific Islands. These communities rely on his second book, Disabled Village Children, as their comprehensive guide; it also has been translated into many languages. |

|

For a deeper dive into current news and analysis in English, check out our media website. And definitely see the new English podcast ¡Soberanía! (Sovereignty) with José Luis Granados Ceja and Kurt Hackbarth. They entertain, while dismantling the lies and distortions about Mexico fed to us by the mainstream media. |

|

Don’t miss an issue! Sign up for a free Mexico Solidarity Bulletin subscription. |

|

|

Rural Rehab Program Run by Disabled Villagers |

|

Author and health and social justice activist David Werner is co-founder and director of HealthWrights and was a visiting professor at Boston University’s International School of Public Health. A biologist and educator by training, he has worked for over 50 years in village health care, community-based rehabilitation, and child-to-child health initiatives in the Global South, primarily in Mexico. He has authored two books used widely throughout the world: Where There Is No Doctor and Disabled Village Children. |

|

|

In our second interview with David, he tells the story of Project Piaxtla’s sister program, Project PROJIMO, the rural rehabilitation program organized and directed by disabled health workers in the village of Ajoya, Sinaloa. Drawings by David Werner.

After years working with the Project Piaxtla health program, how did the rehabilitation program, Project PROJIMO, begin? |

|

|

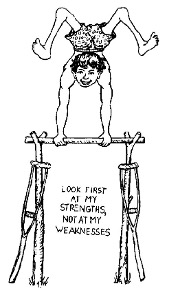

David Werner: It happened in stages. Several Piaxtla health workers, chosen by their villages, happened to have disabilities. In selecting health workers, before we suggested any names, we asked them first to list the characteristics they’d like to see in their health worker, including traits like kindness and concern for those most in need. Because some of the people with disabilities had themselves experienced discrimination or being made fun of as children, they tended to be particularly understanding of others with special needs. |

|

|

Climbing the mountain |

|

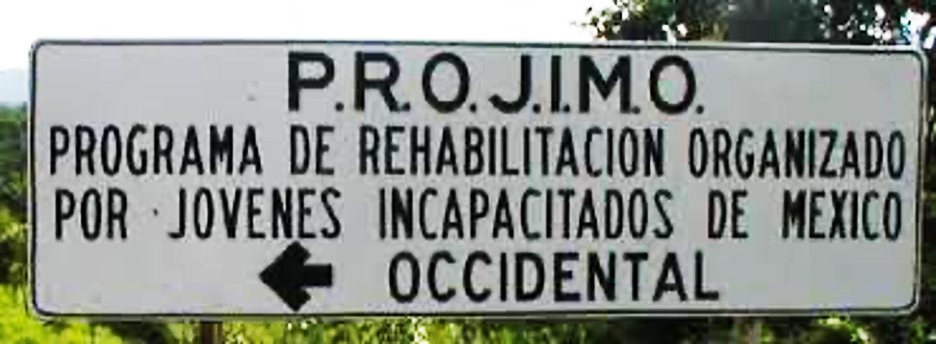

Indeed, some of the disabled health workers became among the most conscientious promotores de salud — their “weaknesses” became their strengths. In time, some disabled health workers became leaders of the village health program — and eventually founders and leaders of the Programa de Rehabilitación Organizado por Jóvenes Incapacitados de México Occidental, or PROJIMO. Prójimo also means beloved neighbor. |

|

In the 1960s, when WHO and UNICEF were first promoting primary health care in the Global South, Project Piaxtla was being born in Mexico’s Sierra Madre. Correspondingly, in the 1980s, when WHO and UNICEF were introducing Community Based Rehabilitation (CBR) in poor countries, disabled villagers were launching Project PROJIMO as a sister program to Piaxtla.

Both Piaxtla and PROJIMO — and the books they inspired — influenced the direction of the evolving international approach to primary health care (PHC) and CBR. Their contributions made these programs — initially designed by western professionals — less hierarchical and more genuinely community-based. Three Swedish professionals, who developed CBR together with WHO and UNICEF, initially instituted a very top-down structure. The program’s international coordinators coordinated the national coordinators who coordinated the district coordinators who coordinated the village coordinators who coordinated the family coordinator who coordinated the disabled family member. The “professionals” named this hierarchical pecking order Community Based Rehabilitation!

How were “community-based” programs in Latin America similar to or different from actual community-based programs? |

|

The striking contrast between villager-run and government-run programs became clear to us early on with the so-called Community Based Health Programs (CBHPs). |

|

|

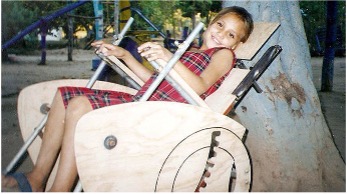

A disabled girl sitting proudly in her specially adapted chair |

|

In 1972, the wide use of my book Where There Is No Doctor led to interchange among these emerging programs throughout the Americas, and a few of us in the Piaxtla team visited programs in Mexico, Central America and northern South America. Some programs were government-facilitated; others had been initiated by health workers who identified with the marginalized. In some cases, religious individuals made outstanding contributions by helping villagers design and lead initiatives based on their own needs.

So striking were the differences among the various programs we visited, we classified them along a continuum: community supportive to community oppressive. The community-supportive programs encouraged the poor to be leaders and engage in a process of collective analysis of the causes underlying poor health.

The community-oppressive programs fostered dependency, outside management and services, and unquestioning obedience to rules and regulations.

In sum, while the community-supportive programs were bottom-up and people-empowering, the oppressive programs were top-down and disempowering.

Can you show us some of the people involved in Project PROJIMO? |

|

The inspiration to start Project PROJIMO arose primarily from village health workers in Piaxtla who themselves were disabled. |

|

|

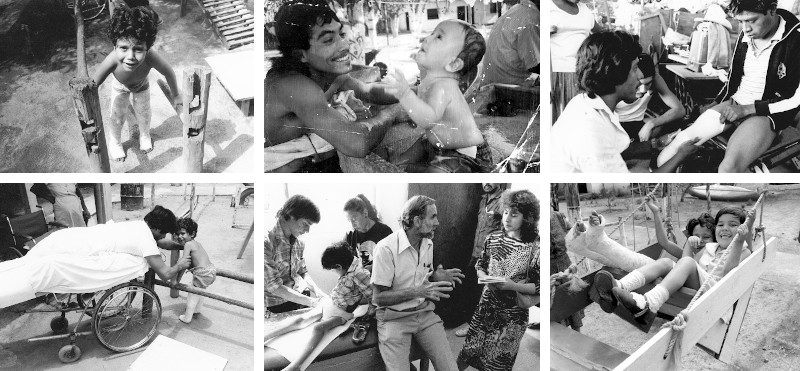

Part of the PROJIMO team |

|

Over the years, they’d done their best to help people with a range of health problems, but they had little experience with disabilities, especially in children. Out of this concern, the idea was born to start a sister program focusing on disability and rehabilitation. Hence PROJIMO was born — run by disabled people themselves. |

|

|

Look first at my strengths, not at my weaknesses |

|

|

Smile! Girl with leg braces riding hand-powered tricycle |

|

Which disabilities has PROJIMO made the greatest impact on?

Mainly cerebral palsy, spinal cord injuries, and polio. When the Piaxtla initiated the vaccination program in the 1960s, polio was common in the Sierra Madre. Marcelo, a boy with disabilities from polio, arrived from a village far up the mountain to work with the Piaxtla team. When PROJIMO began in 1979, Marcelo became an expert brace maker and prosthetist. |

|

|

Mari and Conchita |

|

|

Mónica from the Habilítete Maztlán team |

|

Spinal cord injuries from car accidents and industrial falls are also common. Gunshot injuries are frequent in Sinaloa where cartel violence is rife. Many paraplegics (paralyzed from the waist down) and quadriplegics (paralyzed from the neck down) have come to PROJIMO for support after lives of violence on the streets of Culiacán and Mazatlán. Many with spinal cord injuries become active in the program; two paraplegic women, Mari Picos and Conchita Lara, were leaders of PROJIMO for years. Mari became paralyzed when she was hit by a car while waiting for a bus to take her to her wedding. When Conchita was a little girl, she fell while running, breaking her lower spine. Similarly, Mónica, another disabled woman, works with the Habilítete Maztlán team in the city of Mazatlán, a program organized and run by young disabled and recovering drug addicts.

Why does PROJIMO focus on physical disabilities when worldwide intellectual disabilities tend to be more common?

In a poor rural area such as the Sierra Madre of Mexico, sustaining life depends on physical ability. It’s understandable that people are more concerned about physical rather than mental ability. Hence, PROJIMO developed according to people’s felt needs for physical fitness. |

|

|

|

Today, Project PROJIMO continues to serve disabled people, young and old, from a broad region of western Mexico, despite the program’s financial challenges. No question that the cartel and the high level of violence in Sinaloa have especially affected poor people. I do hold hope that peace and democracy will ultimately prevail in Sinaloa and throughout Mexico, and that disabled people and all in the bottom rungs of society will ultimately be respected as full contributing members of Mexico. Mexico has been my own country for many of my ninety years. Since 2018, and particularly now with our new president, I hope a more peaceful future is in sight. |

|

In addition to the book Disabled Village Children, the World Health Organization has published and promoted David Werner’s article The Village Health Worker: Lackey or Liberator. |

|

|

|

|

|

Facing Down El Charro Negro |

|

|

Mexico City based freelance writer and photojournalist José Luis Granados Ceja previously spent time as a staff writer for teleSUR, and currently works with Venezuelanalysis. His writing on contemporary Latin American democratic struggles can be followed on X (Twitter): @GranadosCeja. |

|

|

Mexican folklore has a figure known as El Charro Negro, said in some cultures to represent greed and exploitation. Pictured as dark and looming with sometimes only a skull for a head, the story of El Charro Negro is meant as a cautionary tale warning of the dangers of outsiders, people foreign to our ways who will defy convention in pursuing self-enrichment. In modern Mexico, it’s hard to think of a figure that better encapsulates the myth of El Charro Negro than newly elected US president Trump.

In her first battle with El Charro Negro, President Claudia Sheinbaum has emerged the victor.

Following Trump’s election victory, Sheinbaum pledged that her government would face any challenges in their bilateral relationship with “dignity” and “pride” and tackle them head-on. Contrast her reaction to that of Justin Trudeau’s as Prime Minister of Canada. His deputy PM hit the panic button and immediately moved to reconstitute an emergency cabinet-level committee to deal with the “urgent issue” that is a Trump White House, comparing this to their response to the COVID-19 pandemic!

When Trump recently doubled down on his threat to impose 25 percent tariffs on goods from Mexico, Canada, and China, it forced Mexico and Canada to respond sooner than expected. Trump was trying to pressure them into more action to stem the flow of drugs and migrants into the United States.

True to her word, Sheinbaum penned a refreshingly candid letter to Trump. She said, in no uncertain terms, that his negotiating methods wouldn’t work, that US tariffs would be met with reciprocal tariffs, and also reminded him of the US role in the cross-border flow of drugs and weapons.

“Seventy percent of the illegal weapons seized from criminals in Mexico come from your country. We do not produce these weapons, nor do we consume synthetic drugs. Tragically, it is in our country that lives are lost to the violence resulting from meeting the drug demand in yours,” wrote Sheinbaum.

Some pundits said the infamously sexist Trump would react poorly to a woman calling his bluff, but Sheinbaum subsequently told the media that the two held a “friendly conversation” concerning drugs and migration. She added that the two had pledged to have an ongoing dialogue about Trump’s concerns. In an underreported piece of the conversation, Sheinbaum told Trump directly that the US should end the blockade of Cuba and Venezuela if he wants to see reduced migration to the US.

For his part, Trump said the two had a “wonderful” and “very productive” conversation.

Mexico’s strategy to confidently face down El Charro Negro appears to be working so far. In a subsequent interview with Sin Embargo, Economy Minister Marcelo Ebrard defended the strategy while poking fun at Canada’s Trudeau, who scurried off to Mar-a-Lago for a talk with Trump.

“I would think that the strategy being followed by President Sheinbaum is much better because she set a very firm position in a letter saying we want to negotiate, but we're not going to rush to see what they want, because if you do that, you'll be run over.” Ebrard told Los Periodistas.

With Trump now threatening 100 percent tariffs on BRICS countries, political analysts speculate that Trump is using the tariff threat as a negotiating tool and that the tariffs are unlikely to happen given the likely devastating economic impact. However, Trump, like El Charro Negro, is notorious for transgressing established norms.

Sheinbaum just demonstrated to the world that the best strategy, in any case, is to face down El Charro Negro directly, with dignity. |

|

|

|

|

Recent news reports and commentaries, from progressive and mainstream media, |

|

Rob Gillies, Canadian officials blast Trump’s tariff threat, and one calls Mexico comparison an insult Los Angeles Times. In a banner week for Canadian diplomatic foot-shooting, Canadian politicians attempting to use anti-China sentiment to convince Trump to cut Mexico out of the USMCA ended up being threatened with 25% tariffs on Canadian exports by the USA’s President-elect. Mexican President Sheinbaum responded to the tariff threat with a stern open letter to Trump that resulted in an amicable phone call that appeared to settle the tariff issue favourably for Mexico. Mexico’s 4T: One, Vassal State of Canada: Zero.

Dulce Olvera y Montserrat Antúnez, Mal vecino, y peor socio Sin Embargo. Canadienses se llevan riqueza de México por casi nada. Y todavía regatean impuestos.

GM temporarily lays off 6,000 workers in Mexico due to strike Agence France-Presse. GM's Mexican arm notified workers at the Silao assembly plant that they had been placed on indefinite, mandatory vacation and would receive 55 percent of their pay, according to an internal document obtained by AFP.

Antonio López Cruz y Enrique Gómez, Morena presenta reforma para reducir a 40 horas la jornada laboral El Universal. Mientras que afuera de la Cámara de Diputados, la activista María Luisa Luévano, se mantiene en huelga de hambre para exigir la aprobación de la reforma para reducir a 40 horas la jornada laboral, adentro el diputado de Morena, Manuel Vásquez Arellano presentó la misma iniciativa.

Diana Baptista, Mexican female gig workers push to fix "sexist" algorithms Context. Female delivery workers want deeper changes in the upcoming gig work labour reform to tackle what they see as entrenched sexism on online platforms. This includes modifying app algorithms to assign them smaller packages, ensure they are not sent into areas with high rates of gender-based crime, and a guarantee of equal pay.

Ulises Rodríguez López, Sheinbaum pone en su lugar a político de Canadá que minimizó a México Polemón. La Presidenta Claudia Sheinbaum Pardo declaró que su gobierno no acepta el tipo de declaraciones que hizo Doug Ford, primer ministro de Ontario, Canadá, pues reiteró que México, Estados Unidos y Canadá deben de ser vistos como iguales.

David Bacon, Domestic Workers: A New Face of International Solidarity The Reality Check. In the US and Canada, rising activism has accompanied the increase of immigrant workers in the domestic worker labor force. This wave of migration was in part the product of the displacement of families and communities in Mexico under the impact of NAFTA, as it adopted neoliberal structural adjustment policies.

Alonso Urrutia y Alma Muñoz, Coordinación, no subordinación, con EU para enfrentar migración y tráfico de fentanilo: Sheinbaum La Jornada. Al referirse nuevamente a su conversación con Trump, Sheinbaum aseveró que no hay diferencia entre los planteamientos que se le hicieron a Trump en la carta con el contenido de la conversación telefónica.

David Mantey, General Dynamics Subsidiary to Pay $1.4 Million in Back Wages to Mexican Engineers Yahoo! Finance. An investigation by the DOL's Wage and Hour Division found National Steel and Shipbuilding Co. (NASSCO) used the L-1B visa program to bring the workers to San Diego from a General Dynamics subsidiary in Mexicali, Mexico, to install power plants, engines and machinery; complete structures and finish and furnish ships interiors.

|

|

|

|

|

The Mexico Solidarity Project brings together activists from various socialist and left organizations and individuals committed to worker and global justice. We see the 2018 election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as president of Mexico as a watershed moment. AMLO and his progressive Morena party aim to end generations of corruption, impoverishment, and subservience to US interests. Our Project supports not just Morena, but all Mexicans struggling for basic rights, and opposes US efforts to undermine organizing and Mexico’s national sovereignty.

Editorial committee: Meizhu Lui, Bruce Hobson, Agatha Hinman, Victoria Hamlin, Courtney Childs, Pedro Gellert. To give feedback or get involved yourself, please email us! |

|

Subscribe! Get the Mexico Solidarity Bulletin in your email box every week. |

|

Web page and application support for the Mexico Solidarity Project from NOVA Web Development, a democratically run, worker-owned and operated cooperative focused on developing free software tools for progressive organizations. |