|

|

|

|

The weekly newsletter of the México Solidarity Project |

|

|

|

Online at mexicosolidarityproject.org |

|

June 29, 2022/ This week's issue/ Meizhu Lui, for the editorial team |

|

|

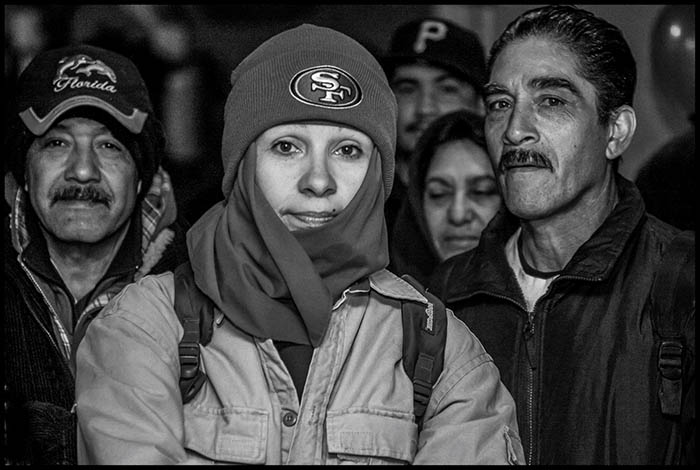

The 2019 Matamoros maquiladora strike. Photo: Esteban Martinez. |

|

Labor of Love: A Great Gathering in Chicago |

|

At supermarkets across the United States, all the avocados come from México. Limes too. But the biggest Mexican export? That remains laborers.

If everyone living in the US today started counting off by tens, one out of every ten of us would be of Mexican descent, 36 million people in all. These folks are now working in every U.S. industry. They dominate in critical and growing sectors of our economy, from agriculture to hospitality and caring. They stand rooted in a history of labor militancy and have become active as union activists, officers, and staff. They could hardly be more important to the future of our US labor movement.

Thank goodness that Labor Notes, the organization that’s spent decades bringing together rank-and-filers to “put the movement back into the labor movement,” understands that importance. At the 2022 Labor Notes annual conference, held earlier this month in Chicago, the gathering’s organizers recognized that Latinx must have spaces of their own and not just be integrated into the mainstream English language workshops.

Understanding the concerns of Latinx workers, Mexicano unionist Gabriel Mireles explains in our interview this week, would help organizers of all races learn how to uncork Latinx energy. But, overall, even labor progressives haven’t fully recognized the significance of international solidarity. Worker movements in other countries still strike far too many US labor organizers as interesting sidelights largely marginal to their busy-as-hell lives.

We need to take down our own “border walls.” If we did, we would open the floodgates to coordinated and mutually beneficial action. Achieving real cross-border worker solidarity — especially with México, the biggest economic partner of our US capitalist class — would be a game changer.

Building a vital, vibrant labor movement will always be a labor of love. Kudos to Labor Notes for providing us with a unique space for sharing that love across borders as we organize, together, to take those borders down. |

|

|

|

Don’t miss an issue. Subscribe to the weekly México Solidarity Bulletin! |

|

|

|

|

Labor Notes 2022: The Centrality of Solidarity |

|

Gabriel Mireles, a Boston-based Mexican-American labor organizer and union staffer, has spent years organizing in low-income immigrant communities across Massachusetts to help people realize their power through collective action. Nationally, Mireles helped found the México Solidarity Project, and, as a musician, he’s also using sound and song to connect peoples across cultures. All these experiences give Mireles an ideal vantage point for assessing the recently completed 2022 Labor Notes conference.

Immigrants usually want their kids to rise above the working class. But you decided to place yourself in the union movement. Why? |

|

|

My father’s family emigrated to the US looking for work as manual laborers. My father belonged to AFSCME, but he didn’t talk about the union much. He wanted me to choose a job not just to survive, as he had had to do, but to choose my own profession and to make more money than he had. Isn’t that what every parent wants? I studied at Berklee College of Music but didn’t graduate. I did have to find work to survive!

I worked as a phone fundraiser, in a unionized workplace, and unintentionally became a union steward, then joined the negotiating committee — and found that while I still wanted to make music, I loved worker organizing as well!

The Labor Notes annual conference, earlier this month, had an Encuentro with a full agenda for Latinx workers. What was that all about?

Labor Notes recognized the need for this day-long track based on the huge number of Latinx workers in the US, the labor struggles they’ve led in sectors where they predominate, like farm work and day labor, and the special barriers to unionization that workers who are immigrants face. The conference clearly needed this space. We had full Encuentro workshops, with about 50 activists in each one, most of them Mexicano.

These workshops showed the close interrelationship between immigration and labor struggles. We explored sanctuary unions, worker centers that help workers with more than workplace issues, and cooperatives controlled by workers themselves. We analyzed how the federal H-2A visa program for temporary agricultural workers only increases the exploitation of immigrant labor. |

|

Do you see commonalities between Mexican worker-led union organizing and the worker-led organizing now going on in the US at Starbucks and Amazon?

What strikes me the most here: We may have, in both México and the US, decent labor laws on the books, but companies are constantly flaunting these laws and workers have to deal with that. The Biden administration is paying lip service to supporting unionization, but not delivering actual support. At the Labor Notes conference, workers from the state-run Mexican news service Notimex spoke about their two-year-old strike that the avowedly pro-labor Mexican government won’t settle. |

|

|

A flyer from the Notimex struggle |

|

You had a chance to hang out, at Labor Notes, with labor folks from México. What effect did that have on you?

It’s one thing to read a story about a historical event, it’s another to hear an actual participant telling that story. I had read the book El Golpe by Rob McKenzie about an attack by goons at a Ford Plant in México in 1990, so when Hector de la Cueva, one of the Mexicans at the Labor Notes conference, told he was one of the striking workers that day, I felt history coming alive. And then just hanging out with him, getting to know him across the breakfast table, turned out to be very cool. I’m really happy to have made personal connections to activists from my home country.

Did US unionists come away from the Labor Notes conference with a better understanding of why international solidarity must be part of their work? |

|

At the conference workshops, Hector and Israel Cervantes, a leader in the struggle of General Motors workers in central México, spoke to a mainly Latinx audience. I wished that more non-Latinx had come. Labor Notes brought them both to Chicago and gave Israel a plenary role. I hope they continue to do more of this.

But I think we need a stronger case made for “workers of the world to unite.” In this globalized economy, we need to always organize in ways that recognize that US workers affect — and are affected by — what happens to workers in the rest of the world. |

|

|

Fired GM workers. Photo: WSWS.org |

|

Israel and Hector both see international support as a big factor in the success of the new independent union SINTTIA at General Motors. Labor Notes and the México Solidarity Project raised money for that struggle, circulated petitions, and helped unions and community groups pass — and then send to the GM CEO — resolutions demanding fair contract negotiations and the reinstatement of the fired workers

It’s a lot harder to step on worker rights when the whole world is watching! |

|

|

Much More Than a Wall/Más Que Un Muro |

|

Not just a wall. Not just a line. The border between México and the United States makes for its own unique region with a history, peoples, and a culture built on love, survival, and shared stories. Photojournalist David Bacon brings the dimly lit realities of this region into sharp focus in his new book, More Than a Wall/Más que un muro. Bacon offers here more on his life’s work and how he hopes his fascinating new book will contribute to it. |

|

|

|

I’m what you would call a social movement/ |

|

I knew some of those involved and began documenting the strike. Since I had been a union organizer for a long time, the whole question of a strike was something I was very familiar with already. So my purpose was not just to show the reality of what was happening. Part of it was very concrete — to get support for the union. |

|

|

Santiago Juxtlahuaca, Oaxaca, 2008. Zacarias Salazar with a wooden plow. |

|

It’s interesting the way the political histories of our two countries track each other. The McCarthyite purge of alleged communists in the US and the repression of the left in Mexico during the same period run very similarly. Each country has its own dynamic, but we have a lot of points where we touch each other. People in the US can learn a great deal from Mexican artists and photographers. |

|

|

Calexico, California, 2010. Workers bundle up against the cold. |

|

From the beginning of the 1990s I could see that the border was something that needed explanation. It needed articles. It needed photographs for us to understand what was going on. Anyway, the book gets produced because I keep going back and going back and going back. |

|

|

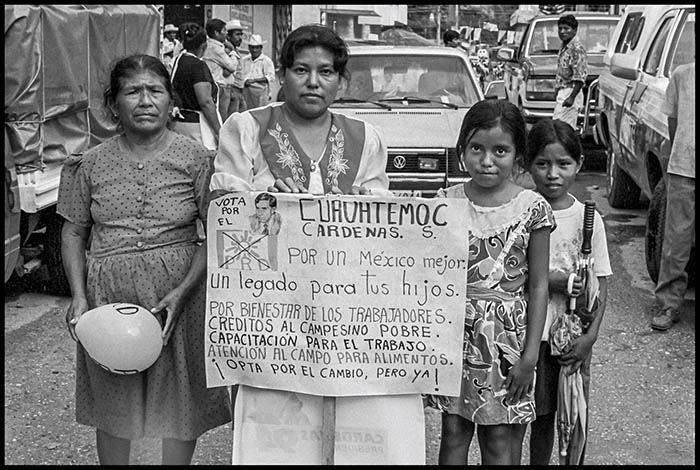

Tijuana, Baja California, 2000. A Family supporting the campaign of Cuautémoc Cardenas. |

|

|

Recent news reports and commentaries, from progressive and mainstream media,

David Bacon, Reviving the Bracero Program Is the Wrong Answer for Workers, The Nation. Not even Biden’s own Labor Department believes that the administration’s proposal to bring in more seasonal farm labor will improve working conditions.

Ulises Rodríguez López, AMLO: conservadores son cínicos al criticar violencia que Calderón provocó, Polemón. López Obrador ha llamado cretino y cínico al expresidente por criticar la violencia en el país y defendió la actual estrategia de seguridad contrastada contra la de responder a la violencia con violencia.

Bruce Baigrie, The Mexican Energy Option, Consortium News. AMLO’s energy reforms are reasserting energy sovereignty over an increasingly foreign private sector that owns most of Mexico’s renewable energy, in a battle that offers an essential example for the left — and for South Africa’s especially.

Visibiliza IPRI patrones de criminalización hacia pueblos indígenas en México, Servicios para una Educación Alternativa A.C. La red Iniciativa Global por los Derechos de los Pueblos Indígenas (IPRI, por sus siglas en inglés) ha presentado su informe “El asedio y el desprecio”, sobre violaciones de los derechos humanos contra los pueblos indígenas.

Jorge Antonio Rocha, México issues arrest warrants for former security chief currently detained in the US, Aztec Reports. The former head of public security under former President Felipe Calderón retired to a lavish lifestyle in Miami after leading the infamous War on Drugs that left 70,000 dead and criminal gangs riding high.

Con votación unánime, la comunidad de Nuevo Zirosto decide autogobernarse, La Coperacha: Informacion cooperativa fresca y solidaria. En Michoacán hay 25 Consejos de Gobierno Comunal que reciben el presupuesto de forma proporcional a su población y de manera directa, para mantener sus respectivos Planes de Desarrollo Comunal y su propio sistema de seguridad que son las Rondas Comunales. |

|

|

The Mexico Solidarity Project brings together activists from various socialist and left organizations and individuals committed to worker and global justice who see the 2018 election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as president of México as a watershed moment. AMLO and his progressive Morena party aim to end generations of corruption, impoverishment, and subservience to US interests. Our Project supports not just Morena, but all Mexicans struggling for basic rights, and opposes US efforts to undermine organizing and México’s national sovereignty.

Editorial committee: Meizhu Lui, Bruce Hobson, Bill Gallegos, Sam Pizzigati, Courtney Childs, Victoria Hamlin, Agatha Hinman, Steven Hollis. To give feedback or get involved yourself, please email us! |

|

|

|

Web page and application support for the México Solidarity Project from NOVA Web Development, a democratically run, worker-owned and operated cooperative focused on developing free software tools for progressive organizations. |