|

|

The weekly newsletter of the Mexico Solidarity Project |

|

Every issue archived online at mexicosolidarityproject.org/archives/ |

|

October 22, 2025 |

|

|

|

Making Social Change out of Small Change |

|

Meizhu Lui, for the editorial team |

|

|

Bruce with an ex-miner, selling artisan products made with mined minerals, Mirador de Rayas, Guanajuato |

|

In Guanajuato, my friend Bruce Hobson and I were parked in a public parking garage. To get out, you had to put coins in the box at the exit. I only had a credit card. He pulled out his change — one peso short! Late for a bus, we dashed up to the street to beg strangers for the gift of a peso.

People who sell their wares on the streets often face tiny but catastrophic shortfalls of cash. Where do they turn when an old pot wears out or when they run out of cloth to make more embroidered blouses? What stranger will help?

In 1976, Muhammad Yunus saw how women villagers in Bangladesh struggled to survive. Too poor to participate in the banking system, they borrowed from moneylenders, whose high rates of interest trapped them in a cycle of poverty with most of their income going to pay the usurers. Yunus made small loans to the women out of his own pocket and learned these allowed the women to expand their businesses, take home more money and achieve some financial security. He was able to convince a bank, with his own money as collateral, to make microloans at affordable rates. The women paid off the lenders faithfully.

In Mexico, Rocío Mejía is in charge of granting microloans for small, mostly women-owned businesses. But the public sector’s pockets, like Yunus’s, aren’t deep enough to meet the needs of millions of microenterprises. Like Yunus, Mejía and the Sheinbaum government are now asking traditional banks to take their program to scale.

The capitalist world’s interests lie in the macro; the bigger the business, the better. Turning neoliberalism upside down, Rocío knows that paying attention to the tiniest businesses not only combats poverty but also contributes to building Mexico’s economic future. |

|

|

Financial Reform: Well-Being Requires Money |

|

|

Rocio Mejia Flores has served in top government positions in Mexico City and the national government as an expert in microfinance. In 2002, then-mayor López Obrador appointed her as Director of FONDESO, the Mexico City Social Development Fund. As president, he appointed her as Director General of Telecommunications of Mexico (Telecomm) in 2022. She was reaffirmed in that position by President Sheinbaum, and the name of the department was changed to FINABIEN. A major proponent of Feminist Economics and Solidarity Economics, she promotes the economic empowerment of migrant women, women in maquiladoras, women microentrepreneurs, rural producers, Indigenous women and Afro-Mexican artisans. |

|

Photos below by Vicky Hamlin unless otherwise noted.

In your 25 years in public office, you’ve focused on microenterprises. What are microenterprises and microcredits?

People without jobs in the formal sector open laundromats, taco stands, car washes to make a living. They are considered microenterprises when they have fewer than 10 employees; they represent 85% of all businesses in Mexico.

When López Obrador was mayor of Mexico City from 2000 to 2006, he wanted to help those at the bottom of the economy, including struggling microenterprise owners. To sustain themselves, these people might need a small infusion of money for equipment like a new oven or to repair a broken sewing machine. Private banks don't lend on such a small scale, so their only option was predatory private lenders, who demand up to 100% annual interest. |

|

|

Worldly assets, Mexico City |

|

AMLO launched a publicly funded program offering microcredits, which are small loans ranging from $300 to $1,000 with zero percent interest. In 2018, as president, he made microfinance into a national program, which has continued under President Sheinbaum.

Internationally, microcredit is associated with women, beginning in 1976 with Muhammad Yunus, who discovered that in Bangladesh lending small amounts of money to women selling wares on the streets changed their lives. Were you inspired by his work?

Yes! In fact, when we launched the program in Mexico City in 2001, Yunus visited us, helped us design it and provided feedback on our progress.

Microcredit is available to both men and women, but it’s most useful for women, who are unpaid caregivers in the home, responsible for children, the elderly and a multitude of domestic tasks. They turn to self-employment for money to survive — bakeries, sewing services, ice cream shops and other businesses they can run from home; 77% of our borrowers are women. |

|

|

A family affair, Mexico City |

|

The United States greatly restricts street vending. But in Mexico, if you live in a rural area or small town, you can cook something at home and sell it in front of your house, from your window, on your street — wherever its convenient. Though in large cities like Mexico City, you do need a permit from the borough mayor's office to sell your products on public sidewalks.

What are the tasks of your government department, the Financiera para el Bienestar, “Financing Well-Being,” better known as FINABIEN?

FINABIEN is a money transfer service. Its two main functions are managing remittances and granting microloans.

Originally, the public entity in charge of money transfers was called Telecomunicaciones de México because for the past 100 years, sending money — cash-to-cash — was done by telegram. The big telegram companies have always been foreign, such as US-based Western Union and MoneyGram. They charge exorbitant fees for transferring money between countries, and they don’t have offices everywhere, especially not in rural areas.

AMLO tasked our department with solving these problems. We changed the name from Telecomunicaciones to FINABIEN and created our own low-cost money transfer system that does not use telegrams. With a FINABIEN-issued card, you can pay for utilities, send money and accept remittances. Having our own financial services agency means avoiding the high fees of companies like Western Union, which takes the money back to their home countries. Two billion dollars move through transfer programs every year. Now, all the people’s money will stay in Mexico. |

|

|

FINABIEN cards, pesos or dollars: Bienestar photo |

|

Mexicans abroad can apply for a FINABIEN card online at tarjetafinabien.com/us/ or at a consulate. From the US, they can send money home in dollars, and their families will receive it in pesos. We charge $2.99 per transaction (the lowest rate in the country), and a person can send up to $2,500 per day or up to $10,000 per month.

On January 1, 2026, Trump will impose a new 1% tax on remittances. Mexicans should get their FINABIEN card right now so they can avoid the tax!

Also through the FINABIEN card, Mexicans who are deported from the US can get low-interest loans to help them relocate their micro and small businesses to Mexico. |

|

Where can people get access to the money sent to them from the US? |

|

In 2018, AMLO created Banco del Bienestar, a new public bank with 2,700 branches across the country, including in remote areas. Before, 70% of private banks were foreign-owned, including giants like Santander and ScotiaBank, who charge high transaction fees and don't handle small accounts. Therefore, many Mexicans don't open bank accounts and still use cash for everything. |

|

|

Banco del Bienestar, Bacalar |

|

But when AMLO created new social programs that were meant to put cash directly in the hands of students, people with disabilities, and seniors, a way for them to receive the money was needed. Payments are now made directly into Banco del Bienestar accounts available to all, including the poor, and remittances can also be directly deposited through the Finabien card. The cash can be withdrawn from any of its many branches.

Direct cash payments are a strategy for generating income to reduce poverty. But you wanted to add a strategy for building assets. Why do people need to build up savings and assets, beyond an income? |

|

|

A family pińata business, Guanajuato |

|

Mexico doesn't have a savings culture. People may save up for something like a quinceañera party, but not for the future. Saving was less important when children automatically took care of elderly parents, but that has changed. Because traditional banks require initial deposit amounts that are out of reach for many, we invented a different kind of savings program: government bonds. You can buy a Treasury Certificate (CETES) with 300 pesos, or $15.00, and add money to it. So far, we have 10,000 of these accounts. Savers are investing in Mexico's future as well as their own! |

|

Does the Morena government plan to expand microcredits?

Owing to 40 years of neoliberal economics, more and more people were forced to turn to self-employment; today, over 60% of the population still works in the informal sector.

President Claudia Sheinbaum's Plan Mexico charts a five-year path to a stronger, more self-sufficient economy. It seeks national and international investment to boost the formal sector and to enable people to access jobs paying at least the minimum wage — which increases every year — and to access pensions and other social safety net benefits. |

|

The Plan does not include more funds for microloans. But, frankly, the loan amounts granted through FINABIEN are too small to make a significant impact. The president proposes that private banks provide the resources the government lacks. The goal is for 30% of microenterprises to have access to credit, which will require private banks to offer microfinance at reasonable interest rates. Our government is already negotiating this with the banks.

Microenterprises play a positive role in our economy. Their products are made in Mexico, earnings are spent in Mexico so that money circulates to other Mexican businesses, and they are integral participants in our local communities. |

|

|

A family feeds the neighborhood in front of a Guanajuato government agency |

|

It's exciting to work on a program that contributes to the national goal of ensuring the well-being of all, but first — not just the poor, but poor women! |

|

|

|

|

How Mexico’s School Junk Food Ban Evolved |

|

|

This article by Brenda Marquezhoyos originally appeared in the October 9, 2025 edition of El Sol de México. Jay Watts translated the article, and we have edited for clarity and length. |

|

Remember when recess tasted like chips, soda, and cookies? Well, those days are a thing of the past. These days, Mexican school hallways smell more of fresh fruit than fried foods, and that — though it may sound tragic to some — is part of a silent but profound transformation: the banishing of junk food from the national education system.

Yes, the same policy that many believed impossible (Will children really want to eat jicama?) is already yielding results. According to the Ministry of Public Education, or SEP, 86% of the country’s schools have stopped selling junk food in their school cooperatives (organizations of students and teachers who raise money and provide snacks and school supplies), consolidating one of the central pillars of the Live Healthy, Live Happy strategy promoted by the government.

Five court rulings set an important precedent: the right of children to a healthy school environment trumps commercial interests.

The SEP’s strategy seeks something more ambitious than just changing the menu: re-educating the eating habits of an entire generation.

“The well-being of children and adolescents is a priority. School is a place where we learn, but also where we form lifelong habits,” explained Mario Delgado Carrillo, head of the SEP (Ministry of Public Education). He said nearly 2 million people — teachers, administrators and families — have received online training to promote a culture of healthy eating.

In addition, SEP distributed 300,000 copies of the Manual for People Who Prepare, Distribute, and Sell Food in Public Schools. The goal? For cooperatives to abandon ultra-processed products and offer options that are nutritious but not boring. Now they offer fruit, water and healthy cakes instead of fried foods and soft drinks.

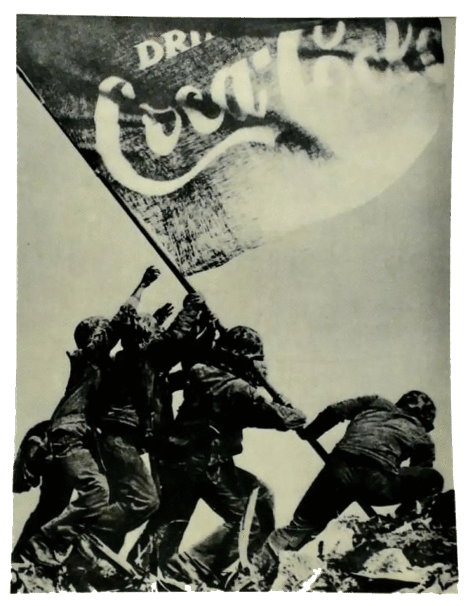

But behind the change lies a battle that was also fought in the courts. The SEP won five court rulings supporting the ban on selling junk food in schools, despite appeals filed by Coca-Cola through two of its subsidiaries — a chamber of commerce and a private university. Federal courts in Mexico City and Baja California handed down the rulings and set an important precedent: the right of children to a healthy school environment trumps commercial interests. |

|

|

|

Recent news reports and commentaries, from progressive and mainstream media, |

|

Sheinbaum Not to Attend the 10th Summit of The Americas Telesur. Mexico rejects exclusion of Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela.

Cuba y Venezuela apoyan a México con equipos de rescate para atender emergencia por inundaciones RT. La Habana y Caracas expresaron su solidaridad con el Gobierno de Claudia Sheinbaum y la población mexicana afectada por el desastre natural.

Javier Cabral, Mexican Farmers Shut Down Highways In National Strike, Demanding Better Prices For Their Produce L.A. Taco. The dramatic actions—showing farmers at times dumping their limes and avocados—are a direct challenge to president Claudia Sheinbaum's administration, demanding an end to NAFTA flexibilities and other policies that farmers say are destroying their livelihoods.

México confirma 76 fallecidos y 36 desaparecidos por intensas lluvias Telesur. Veracruz se reporta como el estado con mayor número de fallecidos, con un total de 34, mientras 14 personas continúan desaparecidas.

Jorge Antonio Rocha, Death toll at 72 in Mexico following intense floods Anadolu Agency. Number of fatalities climbs as affected regions remain under state of emergency.

Gabriela Rodríguez, México: a mujeres, el doble del trabajo doméstico y de cuidados La Jornada. Las estadísticas confirman una distribución desigual e injusta del tiempo dedicado al trabajo, un tema de interés público, toda vez que las brechas laborales de género son un freno estructural para la economía del país, para la movilidad social y para la autonomía y crecimiento de las mujeres, y en menor medida para la movilidad social de los hombres.

David Bacon, A Revolutionary in Politics and Photography Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung. Tina Modotti joined the Mexican Communist Party in 1926, and combined her politics with the new modernist ideas of directness, sharp focus, and simplicity. That gave her work tremendous impact, including in the U.S.

Montserrat Antúnez, Coca-Cola tuvo por décadas a funcionarios en su bolsillo, desde Salinas y hasta Peña Sin Embargo. Coca-Cola se ha caracterizado por obstaculizar la implementación de políticas públicas a favor de la salud, como se opone a elevar el impuesto a bebidas azucaradas, también por contratar durante los últimos sexenios a funcionarios públicos, con lo que ha logrado extender su poder político.

José Olivares, Mexico president dismisses US claim of cartel bounties on immigration officials Guardian. Sheinbaum says she has ‘no information’ about Trump administration claim as experts also deeply skeptical.

María del Pilar Martínez, Sindicatos independientes impulsan salario mínimo regional y fortalecimiento del Capítulo Laboral del T-MEC El Economista. Las organizaciones sindicales subrayaron que su principal objetivo es aportar, desde la vasta experiencia del movimiento sindical independiente, a la consolidación de políticas comerciales más equitativas, donde los beneficios del comercio internacional se traduzcan en mejores condiciones de vida y trabajo para todos los trabajadores. |

|

|

|

|

The Mexico Solidarity Project brings together activists from various socialist and left organizations and individuals committed to worker and global justice. We see the 2018 election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as president of Mexico as a watershed moment. AMLO and his progressive Morena party aim to end generations of corruption, impoverishment, and subservience to US interests. Our Project supports not just Morena, but all Mexicans struggling for basic rights, and opposes US efforts to undermine organizing and Mexico’s national sovereignty.

Editorial committee: Meizhu Lui, Bruce Hobson, Agatha Hinman, Victoria Hamlin, Courtney Childs, Pedro Gellert. To give feedback or get involved yourself, please email us! |

|

Subscribe! Get the Mexico Solidarity Bulletin in your email box every week. |

|

Web page and application support for the Mexico Solidarity Project from NOVA Web Development, a democratically run, worker-owned and operated cooperative focused on developing free software tools for progressive organizations. |