|

|

|

|

The weekly newsletter of the México Solidarity Project: online at mexicosolidarityproject.org |

|

|

|

May 12, 2021/ This week's issue/ Meizhu Lui, for the editorial team |

|

|

Saving a Language, Saving a People |

|

Years ago, in elementary school, I dreaded having my mother come to meet my teachers or other kids. She spoke with a Chinese accent. It was bad enough looking different, but she sounded different too. Only much later would I realize that, hey, she could speak two languages while other parents could speak only one! Why was I feeling ashamed!

Language supremacy reinforces US white supremacy. Against all common sense, we learn that English equals smart and good and other languages equal stupid and bad. The language-shaming begins in grade school. Native-American kids have had their mouths taped shut for speaking their native language. English-only drives try to keep Spanish out of classrooms. How many immigrant children feel lesser because their parents know more!

Words and concepts in different languages have no one-to-one correlation. The Chinese call some mouth-watering foods “xiang.” No English equivalent exists in either food or language. Hawaiian has at least 15 different words for all kinds of rainbows. We don’t just learn new words when we learn a new language. We learn about another people, about the environment where they live, the activities they love, the concerns they share. Every language we lose represents an extinction event.

Fortunately, we have people among us like Sandra and Rey Mora. They’re perpetuating the learning of our ancestral languages. And they’re helping kids feel pride and not shame when their parents speak English with an accent. They’re reminding us that words — the lifeblood of every people — really matter. Much more about them in this week’s issue. |

|

|

Sandra Gonzalez-Mora and Reynaldo Mora met learning Aztec dance. Their personal and professional partnership, as a writer and an artist, has created an award-winning publishing house, the Skillful and Soulful Press. Their books promote a love of language and encourage families to read and learn together. You can learn more about their independent press online and follow them on social media to stay up-to-date on their latest book projects.

Rey, You have written and drawn a trilingual counting book for very young children, Humingbird/Colibri/Uitsitsilij. Why three languages?! |

|

|

Reynaldo Mora: Growing up, I was called “pocho” by Mexicans because my Spanish wasn’t fluent. And then Americans looked down on me because my English wasn’t perfect. Now I tell them, “I speak two invader languages fairly well!” Sandra and I want children to learn about the languages spoken on these lands long before any Spanish or English word was ever heard. For the first book in this series, from the many indigenous languages, we chose Nahuatl. Over 1.5 million people in Mexico speak Nahuatl today.

These trilingual concept books aim to celebrate indigenous languages and help families introduce their young children to the beauty of the spoken word in diverse cultures. Future books will highlight other languages including Otomí, Navajo, and Mayan, to name a few.

Besides the trilingual book, you’ve written two bilingual books for children age 4-8.

Sandra Gonzalez-Mora: Yes. I’ve been working in the field of early childhood education for many years, and in graduate school I did a research project on bilingual reading materials by Latinx authors that specifically introduce young children to the sophisticated vocabulary critical to their reading development. Finding books that did this introducing proved very challenging. So I realized I’d just have to write and publish them myself!

Do these children’s books serve a political purpose?

Sandra: These books are shifting the narrative that “English is best,” a uniquely American attitude. In Europe, children learn their mother tongue plus two other languages, at least. But here, immigrant kids are pressured to assimilate and made to feel ashamed of their parents and their parents’ culture. That isn’t healthy for children’s development or their family relationships.

Rey: We made a political decision on the spelling we chose for the indigenous words in our counting book. Spanish monks, during their colonization of the Mexica people, developed the “classic” Nahuatl writing system. We decided to use “Huasteca” Nahuatl, a system closer to the way the people themselves understand the language to be pronounced. By using “Huasteca,” we are reclaiming the language and that is powerful!

What do you see as the importance of language learning? |

|

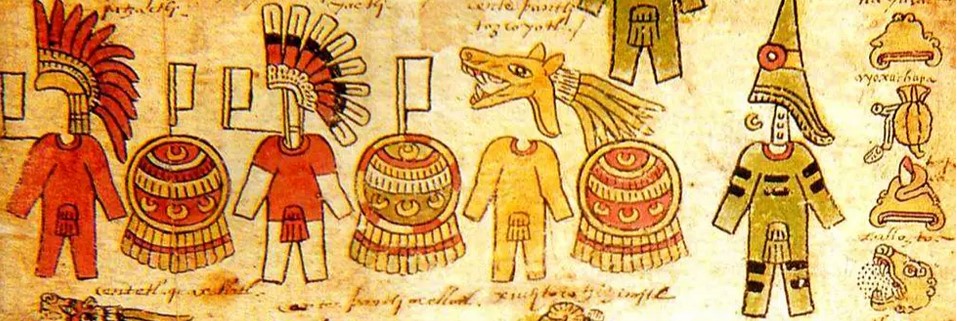

Sandra: Languages reflect the unique ways a people see the world, how they explain what they see, what’s important to them, what role they play in relationship to the rest of nature. Conquerors dominate by stamping out a defeated peoples’ dance, music, worship, farming — and language! The Aztecs had a written language similar to the Egyptians. They used glyphs rather than an alphabet. The Spanish burned many of these historic artifacts. When a language is lost, so are its people. But luckily, many indigenous languages remain alive and well, and we must make sure we keep it that way.

What has been the response to your books, from children and the adults around them? |

|

|

Sandra: People today have become more conscious about the importance of our children being proud of who they are, more willing to see diversity within a school or a society as a plus. Our books have received an enthusiastic reception.

Rey: In keeping with indigenous beliefs about living in harmony with nature, we strive to minimize our carbon footprint. So we don’t print our books overseas. We print them in the US, and that’s getting a positive response. People would like us to sell the books in México as well, so we want to find a local printer there so we don’t have to ship them in. We’re also not selling our trilingual books through Amazon. |

|

Rey, why did you choose the hummingbird to star in your story?

Rey: Hummingbirds, like our peoples, are migratory, traveling thousands of miles each year. In Aztec mythology, it is said that a worthy warrior’s spirit comes back as a hummingbird. Everywhere, people are in awe of these creatures, so tiny, so beautiful, so resilient. Like our children! |

|

|

Do you feel your books can contribute to cross-border solidarity?

Sandra: The Zapatistas have a saying, “A world in which many worlds can exist.” No one country, culture, language needs to dominate over the others. You can live in multiple worlds if you choose, and you can explore your own roots and develop your own sense of belonging. If children can learn this, they’ll make a more peaceful world. |

|

|

Is México a country? A state? A city? An identity? Yes. |

|

|

Diego Rivera, Mural of Tenochtitlan |

|

The very name of the nation of México stands as a constant reminder of the culture of the country’s original peoples, notes Leigh Thelmadatter, a freelance writer specializing in Mexican cultural topics. That holds particularly true, she wrote earlier this month, in the area of the original capital of Aztlán. Centuries of history have never been able to suppress Nahuatl words and language, as this excerpt from her latest México News Daily column explains. |

|

The word México originates in the Mesoamerican era with the Náhuatl word Mexihco (pronounced Meh-SHI-ko) originally referring to the Valley of México. A people called the Mexica migrated south from a place they called Aztlán, established a city on a marshy island in Lake Texcoco, then expanded their domain over the entire valley and beyond.

That valley came to be known as the land of the Mexica, or the Valley of México. The capital, Tenochtitlán, was called both Tenochtitlán and (the city of) Mexico… Tenochtitlán is difficult for Spanish speakers to pronounce, so México was adopted with a pronunciation change to fit Spanish phonetics.

When New Spain was created, it was divided into five provinces, the most important of which was — you guessed it — México, based roughly off the borders of the old Aztec Empire. México City became the capital of both the province and the colony of New Spain…

Under the social order, those born in New Spain were second in status to peninsulares (those born in Spain), yet they felt that they were the “true Mexicans.” For this reason, when independence was achieved in 1821, the choice of name for the new country was México... The use of México reflects that the identity of the country is still highly tied with the city and is reinforced by history, legends and symbols such as the eagle and cactus from the Aztec origin myth, and the Virgin of Guadalupe [La Virgen Morena, the Brown Virgin, who appeared before an Aztec peasant in 1531]. |

|

|

Recent news reports and commentaries, from progressive and mainstream media,

David Reynolds, When Slaves Fled to Mexico, New York Review of Books. A new book tells the forgotten story of fugitive slaves who found freedom south of the border.

John Ackerman, Reforma electoral, urgente y necesaria, La Jornada. El diferendo entre el INE y Morena ha tenido el efecto positivo de colocar en el centro de la discusión pública la necesidad de una nueva reforma electoral que garantice la celebración de elecciones realmente libres, limpias y auténticas en México.

Christine Murray and Avi Asher-Schapiro, Inside Amazon's shadow workforce in Mexico, Thomas Reuters Foundation. Mandatory overtime and 60-hour weeks.

Arturo Sánchez Jiménez, Respalda AMLO política migratoria de EU; "pueden contar con nosotros," La Jornada. El mandatario mexicano manifestó que está de acuerdo con la política emprendida por el gobierno de Joe Biden en materia migratoria.

México Claims Success in Curbing Covid-19, Telesur. Only three federal states remain at a maximum alert level due to the high risk of contagion. |

|

|

The Mexico Solidarity Project brings together activists from various socialist and left organizations and individuals committed to worker and global justice who see the 2018 election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as president of México as a watershed moment. AMLO and his progressive Morena party aim to end generations of corruption, impoverishment, and subservience to US interests. Our Project supports not just Morena, but all Mexicans struggling for basic rights, and opposes US efforts to undermine organizing and México’s national sovereignty.

Editorial committee: Meizhu Lui, Bruce Hobson, Bill Gallegos, Sam Pizzigati. We welcome your suggestions and feedback. Interested in getting involved? Drop us an email! |

|

|

|

Web page and application support for the México Solidarity Project from NOVA Web Development, a democratically run, worker-owned and operated cooperative focused on developing free software tools for progressive organizations. |