|

|

The weekly newsletter of the Mexico Solidarity Project |

|

Every issue archived online at mexicosolidarityproject.org/archives/ |

|

November 12, 2025 |

|

|

|

No Selfies: Photos as Calls to Action |

|

Meizhu Lui, for the editorial team |

|

|

Photo: David Bacon |

|

|

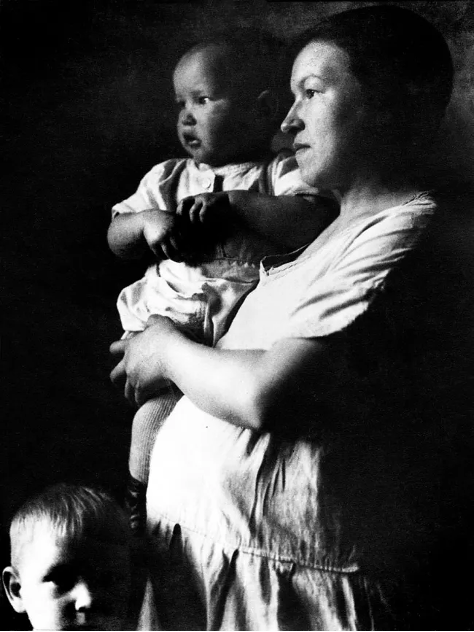

Photo: Tina Modotti |

|

Selfies. Everywhere you go — scenic spot, restaurant, political event — there they are, people taking selfies. Some people have even fallen backwards off cliffs, trying to get just the right shot. Look at me! Oops.

“Self” isn’t found in the images of Mexican photographer Tina Modotti. In the 1920s and 1930s, as photojournalist David Bacon explains, she was a groundbreaking revolutionary photographer — revolutionary in her style and technique and also in her subject matter. She photographed not national leaders, not the rich and famous — the mainstay of popular photographic fare — but workers, farmers, indigenous people and women. She reveals their dignity and resolve, how they struggle against oppressive conditions as they go about their daily lives. Modotti’s photos don’t focus on individuals; she brings to light not the unique, but the universal.

It's a revolutionary task to document the harsh living conditions of working people, how they strive to gain their rightful place as the backbone of any society. A single image in a single instant can sometimes move us to laughter, tears or outrage and then propel us out into the street. Modotti’s photography did all that.

But when the moment called for more, for a different kind of fight, Modotti left off taking photos and took up organizing resistance to fascism. Her legacy is more than a cache of groundbreaking images — it’s a lesson in being a revolutionary.

David Bacon can be counted as a revolutionary photographer of today. His camera's eye and his own eyes look outward, not backward at "self." His life and his photography follow in Modotti’s tradition, focused on the lives of oppressed people and revolutionary struggle. Thank goodness there are still people like David who know who and what demands our attention. |

|

|

Tina Modotti: Woman, Camera, Revolution |

|

Acclaimed photojournalist David Bacon spent 20 years working as a labor organizer for unions where immigrant workers made up much of the membership. His personal experiences with workers around the world, Mexican workers in particular, give Bacon a window into the daily lives of immigrant workers — and a unique insight into the impact of US policy and the global economy on the struggle for global worker justice. Among his books is The Right to Stay Home: How US Policy Drives Mexican Migration.

All photos by Tina Modotti unless stated otherwise. |

|

|

How did Tina Modotti first develop her ideas on photography?

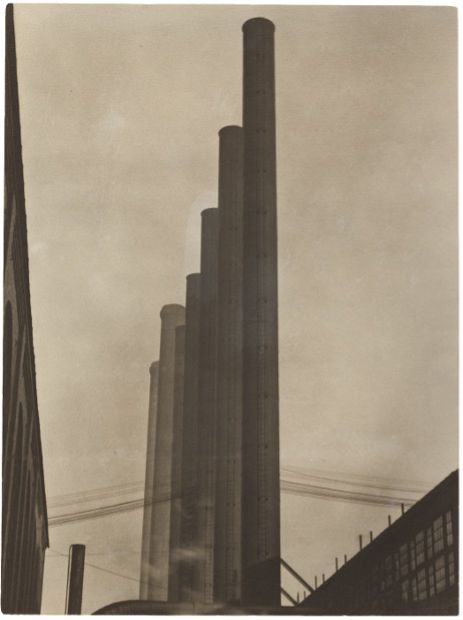

In 1913, at age 16, Modotti’s working-class parents brought her to San Francisco from Udine, in northern Italy. When she moved to Hollywood, she met Edward Weston, a founder of modernism in photography who was discarding the soft-focused pictorialism favored by established photographers. His 1922 images of the Armco steel mill, in their simplicity and sharp focus, were historic in the development of modernism. |

|

|

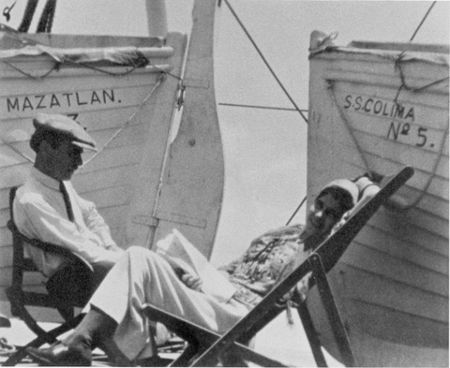

Tina and Edward on the boat to Mexico, 1923. Photo likely by Chandler Weston |

|

|

Armco, Middletown, Ohio 1922: Photo: Edward Weston |

|

From Weston, Modotti acquired technical skills and learned his approach. At 27, she was searching for her way in the world as a photographer and as a woman, and the two went to Mexico together. There, Modotti and Weston became more collaborators than student and teacher.

What was her own approach to photography?

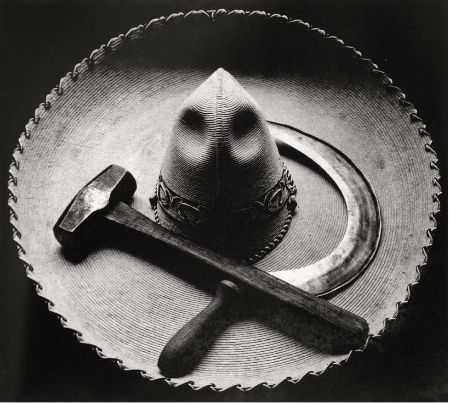

Modotti employed the modernist aesthetic to give her politics greater impact — she had formally joined the Mexican Communist Party in 1927. The modernist style of directness, sharp focus and simplicity infused her work with tremendous power, and her photographs were soon well-known in the US as well as Mexico. Her famous image of a hammer and sickle was a cover for The New Masses at the height of the magazine’s popularity. |

|

|

Sombrero, Hammer and Sickle, 1927 |

|

|

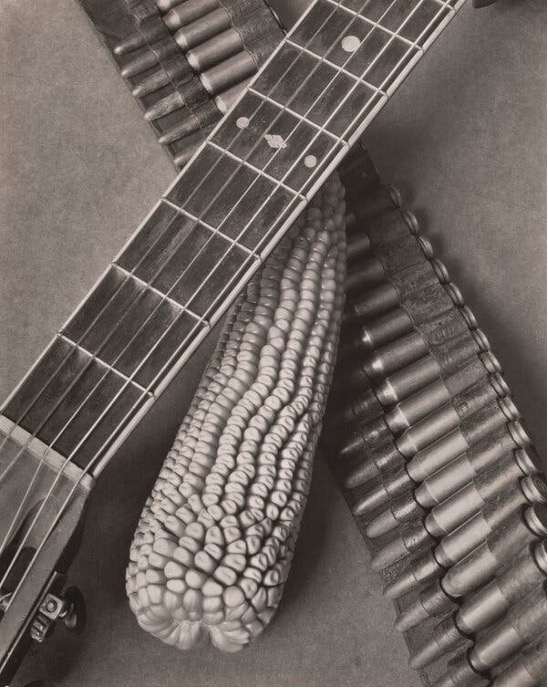

Illustration for a Mexican Song, 1927 |

|

The image was part of a series in which she started with a straight depiction of the Bolshevik hammer and sickle symbol from the Russian Revolution and then gradually removed those images. First, she added a sombrero and then replaced the Russian images with a bandolier, a guitar and an ear of corn. She was “Mexicanizing” communism with symbols that would make sense and provide political inspiration based on Mexico’s own revolutionary history. |

|

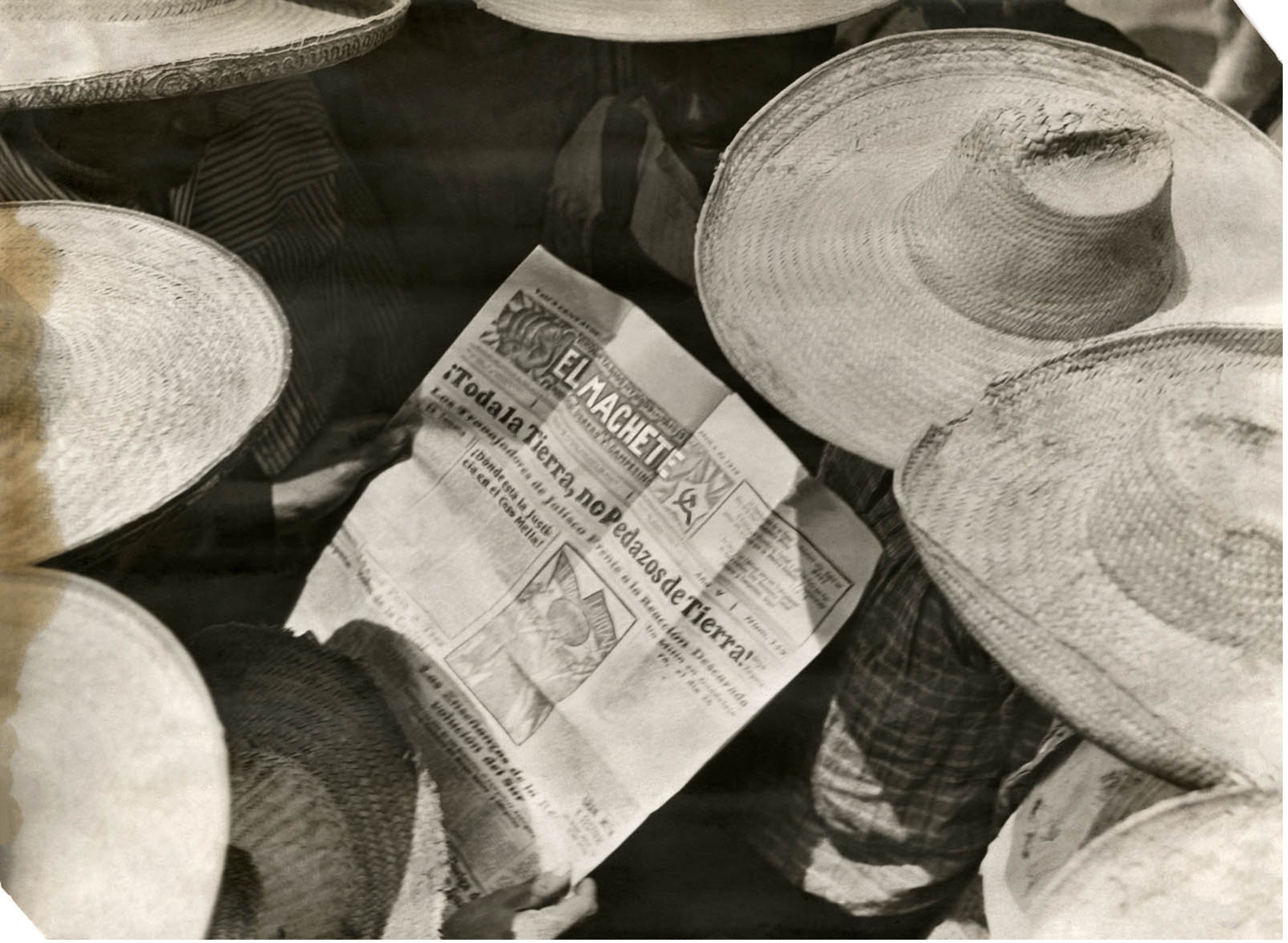

Her image of a workers’ march, her camera catching the massed sombreros of the workers without showing their faces, conveyed a sense of the political power and militance of workers as a class. In another photo, a group of workers are reading a copy of El Machete, the Communist Party newspaper. It illustrated that the paper and its Party speak to the working class and that ordinary people were becoming literate as they participated in politics. |

|

|

Men reading “El Machete,” c. 1927 |

|

Was Modotti a feminist?

Modotti shot luminous portraits of Indigenous women, including a well-known image of a woman holding a baby, in which the light gives their skin and muscles almost three dimensions.

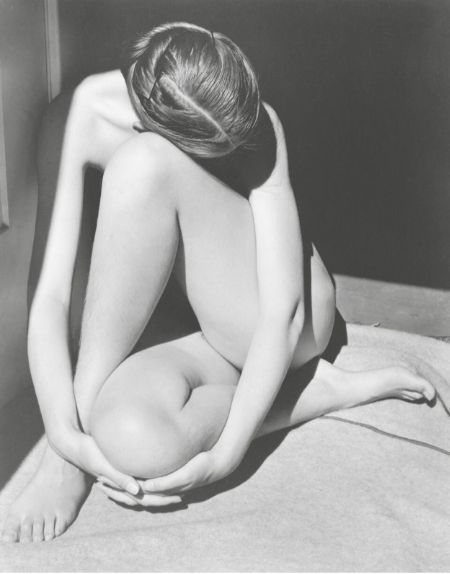

Her genius as an artist, her independent life, and her unwillingness to subordinate herself to men, including Weston, have established her as a major figure in feminist and women’s studies. For instance, she posed nude in several Weston photographs, and these photographs are charged with the photographer’s sexual desire. But looking at them from Modotti’s perspective, as the person in the image, they appear matter-of-fact. She doesn’t face the camera and displays no come-on. The attitude is simply, “This is my body, part of who I am.” |

|

|

Tina Modotti by Edward Weston |

|

|

Two women from Tehuantepec with jicalpextle bowl, no date |

|

But she soon stopped this kind of posing, and we’re left to wonder if she had growing reservations about whether this photography could be a disservice to women.

The thirties were tumultuous years with fascism on the rise. What did Modotti do during that time?

As a dedicated Communist Party member, Modotti spent the second half of her life fighting for revolution. In 1930, because of her political affiliations, Mexico’s incoming right-wing government deported her, along with Vittorio Vidali, the Comintern’s representative in Mexico. The two became partners, comrades and lovers, a relationship that lasted to the end of her life. They went to Berlin, then to Moscow, and then back to Berlin after Hitler took power in 1934, constantly working to support imprisoned or framed revolutionaries.

When the anti-fascist Civil War broke out in Spain in 1936, she went and stayed throughout. She worked as head of Socorro Rojo, or Red Aid, organizing support first for the soldiers and civilian population and then for refugees fleeing Franco. She traveled from city to city, even by boat from Barcelona to Valencia, under the guns of the fascist-occupied coast. As Franco’s armies advanced and the International Brigades left the country in 1939, “I felt anguish in my heart, and I thought about how this was the end,” she recalled. In the following weeks, she helped half a million people make their escape from Barcelona to the French frontier, under bombs and strafing planes. But the fascists tortured and killed many of her comrades.

With no possessions, Modotti left Spain for France, where the Mexican ambassador got her a visa to the US. However, when the Queen Mary docked in New York, immigration authorities refused to let her off the boat. Her sister, Yolanda Magrini, a Communist artist, tried in vain to get on board to see her. Modotti, absent from the US since 1923, was never able to return. She went to Mexico, which gave asylum to many who fled fascist Spain.

What’s her legacy as a photographer?

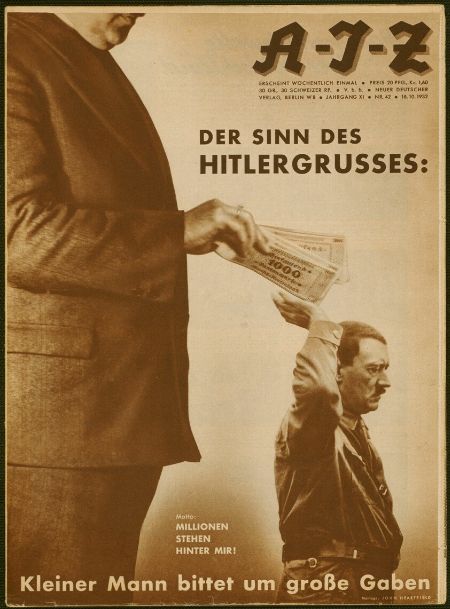

Her photographs from Mexico were widely published by Willi Munzenberg’s AIZ, or the Workers Pictorial Newspaper. |

|

|

A.I.Z. (Worker's Illustrated Magazine, 1929–1934, John Heartfield, German, 1891–1968 |

|

In 1932, in her article, “Photos as a Weapon for Red Aid Agitation,” she argued that photography makes possible the “objective” reproduction of the harsh reality of capitalism, but that images should not merely illustrate text but should speak for themselves.

Modotti herself, however, didn’t return to photography but worked full-time for revolution, giving as her reason her hatred for “the intolerable exploitation of the workers of the countries of South America and the Caribbean” and the “bloody revenge on peasants who fight for their land, the torture of imprisoned revolutionaries, [and] armed attacks on street rallies and unemployed marches.” |

|

Contrary to the bourgeois idea that artists must sacrifice everything for their art, she held the revolutionary view that fighting against fascism and for communism was more important than her photography.

Tragically, she died in 1942 at only 45 years old, in the middle of the war against Nazism, without seeing the final anti-fascist victory.

You are a political activist and photographer as well. Did Modotti influence your own path?

In my work, I’ve come to terms with who I am as a participant in the world and in social movements and see my photography as part of that. I want photographs to have a social function and usefulness, to reflect reality, and to have an aesthetic quality that people can appreciate, even when the immediate circumstances become part of history. |

|

|

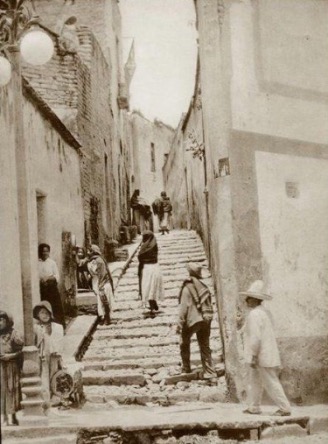

Stairway, 1928 |

|

|

Photos by David Bacon: These images of Portsmouth Square have been assembled into a sequence. |

|

You can look at a photograph Tina Modotti took in Mexico City in 1927, and it's still a beautiful photograph, although the world she photographed has certainly changed. Her purpose in taking photographs, as a social activist, is still clear, and it's a purpose I share. I try to participate in the world to make it a better one, for social justice and to help movements fighting for change. |

|

|

|

|

Assassinated Mayor is No Feast for Vultures |

|

|

Mexico City based freelance writer and photojournalist José Luis Granados Ceja previously spent time as a staff writer for teleSUR, and currently works with Venezuelanalysis. His writing on contemporary Latin American democratic struggles can be followed on X (Twitter): @GranadosCeja. |

|

|

Vultures are circling above Mexico. After the assassination of Carlos Manzo, mayor of Uruapan, Michoacán, the merchants of death who sold us Felipe Calderon’s failed “War on Cartels” are reborn and leveraging this tragedy to reintroduce the same militarization strategy that got us into this mess in the first place. The way that both Mexican and US right-wingers have attempted to feast on Manzo’s body has been nothing but grotesque.

Lilly Téllez from the opposition National Action Party — who has repeatedly appeared on Fox News calling for US intervention in Mexico — ranted in the Senate chamber, screaming at former Senate head Gerardo Fernández Noroña, calling him a “coward, imbecile, and clown” for not crying over Manzo’s death. Moments before her theatrics, the camera caught Téllez asking fellow PAN senator Ricardo Anaya the mayor’s name. She didn’t even know the name of the man that she was supposedly shedding tears for!

Manzo’s body was still warm — a mere 14 hours after the killing — when US Deputy Secretary of State Christopher Landau took to social media, offering “to deepen security cooperation” and expressing his desire for “prompt and effective action” in light of the assassination, using the murder as an excuse for US intervention. Landau, who himself delights in trolling social media users, later lamented that his "condolences" were taken by Mexican readers as political commentary.

Those offering or requesting more “security cooperation” from the US should be honest about what’s on the table. We know what Washington's security policies look like here in Latin America and the Caribbean: drone strikes on civilians.

Advocates of US intervention in Mexico are calling for the bombs currently falling on the Caribbean Sea and Eastern Pacific Ocean to also fall here on Mexican soil.

Make no mistake, Trump wants to strike inside Mexican territory. He hasn’t been able to do it, thanks to President Claudia Sheinbaum’s handling of the bilateral relationship. President Sheinbaum has pulled off a delicate balancing act in the face of a violent and aggressive neighbor, who is demanding a greater US military role inside Mexico. She’s drawn a clear red line on matters of Mexico’s sovereignty.

Although public safety has improved under her watch, security remains a major concern. Together with her cabinet and the local population, Sheinbaum has developed a comprehensive plan to address public safety in Michoacán, one that is focused on her administration’s approach to security.

“The only way to build peace and security is through justice — social justice and a true justice system with zero impunity. That is why the judicial system was reformed, and that is why we must continue to make progress on intelligence, investigation, and prosecution. And that is what we are going to do; that is the path we must follow,” declared Sheinbaum after Manzo’s killing.

One thing is absolutely clear: under Sheinbaum’s watch, Mexico will not return to the failed policies of the past. The vultures will not feast here. |

|

|

|

Recent news reports and commentaries, from progressive and mainstream media, |

|

Ashwin Ravikumar, Mexico City’s Utopias: A Model of Ecosocialism in Practice Socialist Forum. That urban organizers in Mexico City managed to create a forceful social movement with real political muscle under these conditions should give us further confidence that we can too.

Melissa Esquivias y Carmen Pizano, Siguen aflorando casos de corrupción, pero el Comité Ciudadano ni los ve ni los oye POPLab. Mientras presentan otro informe de cifras alegres, se destapa nuevo abuso de poder de Diego Sinhue, exgobernador de Guanajuato, a favor de Mazda.

Pablo Meriguet, Peru breaks diplomatic relations with Mexico People’s Dispatch. The diplomatic crisis comes after asylum was granted to Betssy Chávez, a former minister in Pedro Castillo’s government, who, according to Mexico, is suffering political persecution.

Sandra Hernández García, Aprueban en Comisiones reforma para endurecer penas contra despojos en la CDMX La Jornada. En comisiones del Congreso de la Ciudad de México se aprobó el dictamen de reforma en materia de despojos, que endurece las penas hasta con 11 años de prisión y con más de 113 mil pesos de multa a quien cometa este delito.

Anthony Pahnke, Mexican Farmer Protests are Getting Results – Could their American Counterparts Follow? Counterpunch. Mexican farmers show another way – one where farmers take control over their collective destiny, taking to the streets to call not just for improved economic returns, but dignity.

José Romero, El espejismo del desarrollo: sin industria y sin campo La Jornada. Hoy, los grandes exportadores del agro mexicano ya no son nacionales. Las cadenas más rentables –aguacate, berries, frutas y hortalizas– están controladas por corporaciones extranjeras como Driscoll’s, Mission Produce o Del Monte, que coordinan la producción y la exportación desde fuera del país.

Iran Denies U.S. and Israeli Claims of Assassination Plot in Mexico WANA. The Iranian Embassy in Mexico has rejected recent allegations by the United States and Israel accusing Tehran of plotting an attack against the Israeli ambassador in Mexico City, describing the claims as “entirely false.”

Darren Garcia, Embajada de Irán rechaza acusación de Israel sobre atentado a embajadora Contralínea. Es mentira que la República Islámica de Irán haya planeado asesinar a la embajadora de Israel en México, Einat Kranz Neiger; es información falsa que se compartió de manera muy grave entre los medios y redes occidentales, señaló en conferencia el embajador de Irán en México, Abolfazl Pasandideh.

Mexican President Announces Plan for Peace and Justice in Michoacan Telesur. President Sheinbaum unveiled a three-part strategy to address violence following the assassination of Uruapan Mayor Manzo.

Alejandro Páez Varela y Álvaro Delgado Gómez, Carlos Manzo era afín a la izquierda, no a la derecha, dice su hermano Sin Embargo. El Subsecretario de Gobierno de Michoacán, Juan Manzo, aseguró que la muerte de su hermano, Carlos Manzo, provocó una profunda consternación social no solo en el estado, sino a nivel nacional, por lo que pidió no usar el caso con fines partidistas. |

|

|

|

|

The Mexico Solidarity Project brings together activists from various socialist and left organizations and individuals committed to worker and global justice. We see the 2018 election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as president of Mexico as a watershed moment. AMLO and his progressive Morena party aim to end generations of corruption, impoverishment, and subservience to US interests. Our Project supports not just Morena, but all Mexicans struggling for basic rights, and opposes US efforts to undermine organizing and Mexico’s national sovereignty.

Editorial committee: Meizhu Lui, Bruce Hobson, Agatha Hinman, Victoria Hamlin, Courtney Childs, Pedro Gellert. To give feedback or get involved yourself, please email us! |

|

Subscribe! Get the Mexico Solidarity Bulletin in your email box every week. |

|

Web page and application support for the Mexico Solidarity Project from NOVA Web Development, a democratically run, worker-owned and operated cooperative focused on developing free software tools for progressive organizations. |