|

|

The weekly newsletter of the Mexico Solidarity Project |

|

Every issue archived online at mexicosolidarityproject.org/archives/ |

|

June 25, 2025 |

|

|

|

The Power of Peace to End Violence |

|

Meizhu Lui, for the editorial team |

|

|

|

|

Asking for peace is dangerous, especially if it’s for a peace that means ending the violence enforcing injustice and exploitation. If you dare to speak out against that violence, you yourself will be subject to threat, attack, arrest — even murder. Maria Elena Valdivia found that out at an early age.

Business as usual, whether in an autocracy or a western “democracy,” requires force to maintain the social and economic hierarchy; the sacred business of making money will not tolerate any challenge. And the use of violence trickles down. Poor people — parents, pimps, gangs — sometimes resort to inflicting pain on their own families and neighbors in order to survive themselves.

But there are always those who risk their own safety to protect others, as Maria Elena did in Mexico and Florida. Her kind of courage, when multiplied, can counter the possibility of violence being used against us. We witnessed it when millions of US residents marched in the "No Kings" protest to end ICE's brutal abduction of immigrants and all other abuses of power. Wannabe tough guy Trump threatened “big force” against protesters, and he had the Marines, the National Guard, ICE and the police gussied up in full military gear, ready to beat the public into submission. But to violently attack joyful, creative crowds who showed up unarmed (except for signs that hit him where it hurts — in his ego) would have been a public relations disaster.

That peaceful demonstration of people power deserves celebrating. But we must also celebrate the changemakers who take risks, who extend their hands with compassion and love to oppressed people, who organize for an end to violence. Like Maria Elena. |

|

|

Heads up! The Mexico Solidarity Bulletin will be taking a much-needed break for 2 weeks. We will return on Wednesday, July 16, 2025. Thanks, see you then! |

|

|

Marked by Violence, Promoting Peace |

|

After working herself as a fern cutter in Central Florida, Mexican migrant Maria Elena Valdivia honed her advocacy skills with the Catholic diocese in Wyoming. When she returned to Florida, she was selected by farmworkers to lead the Farmworker Association in Pierson, Florida. She then founded the Migrants and Minorities Alliance and provides a YouTube platform for migrant voices, Luces y Sombras Migrantes, or “Migrant Lights and Shadows.” |

|

|

In 2022, someone threatened to kill you. Who was it? |

|

In 1994, when I came to Florida illegally from Mexico, I worked as a fern cutter with my brother and sister, so I know the hardships that migrant farmworkers endure. But years later I met farmworkers with H-2A temporary visas and learned that they worked under worse conditions than those here illegally!

I started advocating for them, going to the growers, going to the Mexican consulate, going to the Department of Labor. In 2022, I began getting threats. A group of about 30 workers told me that they weren’t being paid and were lied to about a visa extension. Some decided not to complain, but 22 gave me the details of their mistreatment so I could inform the Department of Labor. They also said that their recruiter ordered them not to come back and see me. |

|

|

Alfonso Guevara works with a short-handled hoe, the cortito, that has been banned in California because repeated use causes damage to the spine. Photo: David Bacon. |

|

|

Florida Farmworkers: Photo courtesy Roxana Aguirre, Futuro Investigates |

|

So I started looking for him.

One day, I went to a restaurant where farmworkers ate to give them information about COVID. This big tall guy in a sombrero and boots stood up and came over to me. He got in my face, yelling, “You stay away from these guys.” I didn’t back down. I said, “I’m here about COVID!” I still didn’t know who he was.

Later I was in a long line at the motor registration department, and that same guy was in line. I was on my phone, and he started yelling, “Stop recording me!” I answered “Why would I be recording an asshole like you?” He told me his name — he was the guy I’d been looking for! In front of everyone, he said, “Just beware, people have been found dead on the farms.”

So this wasn't the employer, it was the recruiter! Where did he fit in to the H-2A system? |

|

The growers hire recruiting agencies as their middlemen. These guys go to towns in Mexico and sign people up. The Mexicans have to pay up to 60,000 pesos, around $3000 or more, to get a contract with a grower. But if the worker can’t make enough to pay back the recruiter, they might overstay their visas. If they do go home but still owe money, the guys they borrowed it from to get the visas threaten their families. In some cases, families have lost their homes. |

|

|

Tijuana Contact Center: Photo courtesy Baja Contact Center |

|

|

H-2A visa and payroll card, completing pre-arrival hiring, onboarding: Photo: Ganaz workforce management platform |

|

An H-2A contract is with a single company. Workers aren’t allowed to work for anyone else and must return home after the harvest season. They are open to abuse by the employers, who often force them to work overtime. The work is hot and backbreaking, and sometimes the employers don’t even pay them or don’t pay them by the hour. A manager can say, “You didn’t do too much today, so we’re only going to pay you a little.” |

|

If they complain, they can be sent home and blacklisted. The recruiters call them “snitches,” and they can’t get another H-2A job. It’s not surprising so much abuse goes unreported.

Another reason many workers become illegal is that when they finish at the place they are contracted to, the recruiter lets their visa expire with promises of another job and sends them illegally to another farm. When workers are caught, they’re the ones in trouble. But the recruiter is always risk-free and makes money from both employer and worker, crossing the border freely.

But don't workers at least have the right not to be murdered or beaten up?! Did any of them get help from the Mexican consulate?

Worse than no help. We collected the stories of over 30 fern workers. But at the Orlando Florida Consulate’s Department of Protection, one of the staff was also working as a recruiter himself! What a joke. Their solution — if the worker is having a problem, we’ll send him home! It’s no secret that Florida’s governor, Ron DeSantis, hates migrants. But the two consulates here say, “We can collaborate with ICE.” How are they representing us?

When AMLO was president, I didn’t like him calling us migrants “heroes.” He was just pleasing my ear and did nothing to protect us. In fact, he cut the budget for the consulates and left the same people from the PRI to run them.

We also went to the US Department of Labor with documented evidence that the recruiter brought people here to work illegally and also of the abuse migrants suffered. We still didn’t get justice. The only person to help us was the bishop of the Catholic Church; he intervened and got the growers to at least pay their workers.

You were a migrant farmworker yourself. Why did you leave your home and come to the US? |

|

|

Street sellers: Photo courtesy of Don't Forget to Move |

|

I grew up on the street. At eight, my parents put me out to work selling fruit cocktail, snow cones and candy. I saw older kids abuse younger ones; I saw kids get addicted to alcohol. I saw how parents were exploiting their own kids. So as a teen, I collected toys and distributed them. Then I started to complain to the authorities about conditions for these kids. At 20, I met my husband, and the two of us worked together to help the street kids. |

|

Not everyone appreciated what we were doing; the parents didn’t want us interfering. We were threatened more than once. When I was pregnant with my second child, my husband was murdered. Then, not long after my baby was born, I was working as a cook, and when I came out of the building, someone grabbed me and pushed me into an apartment and assaulted me. When I got away, I called my brother — thank goodness he picked up the phone. He was already in Florida, and he said, “You have to come here right away.” |

|

Within two days, I made my way to Piedra Negras where I crossed the Rio Grande at night with my two children. I had no idea what I would find on the other side — but I had my dreams. |

|

|

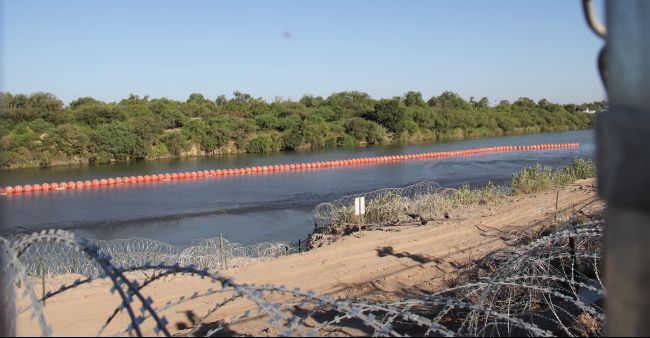

Rio Grande River at Eagle Pass, Texas with unlawful floating marine buoy barrier installed by Texas Governor Greg Abbott: Photo courtesy Eagle Pass Business Journal |

|

That’s how I became a fern cutter, and that’s why my life is about ending violence.

I don’t organize and advocate for migrants as a paid job; I don’t want people thinking that I do it for the pay.

What gives you the courage and determination to keep fighting?

I’m sickened at seeing people abused, especially children. It’s in my nature to stand up for all of us. The solution is for many more of us, and more and more of us, to come together, since it’s being in community that gives us courage. That’s why I became the organizer for the Fern Workers Association. But we need a union, not just an association. Florida doesn’t allow farmworkers to unionize, so we do the best we can.

When it comes to the H-2A program, it’s clearly just legal human trafficking. The US government wants to expand it, as if being “legal” is the answer to migration. We need to cut out the middlemen who are allowed to victimize thousands of H-2A workers every year. We need work certification that doesn’t let one employer own us. I’m fighting for policies that end physical and economic violence, that support the human right for migrants to live in dignity and peace. |

|

|

|

|

The Mexican Flag at the L.A. Protests |

|

By Enrique Acevedo |

|

Enrique Acevedo is anchor of the news program “En Punto” on Televisa. His complete essay can be found in the Washington Post. The article here has been edited for length.

|

|

|

|

|

AP Photo: Jae C. Hong |

|

|

|

I was there as protesters flooded the streets of downtown Los Angeles, their chants rising over sirens and the buzz of low-flying helicopters. The air was thick with smoke. Rubber bullets thudded as they hit pavement and bodies. A wall of L.A. police officers stood at the edge of the crowd.

And above it all, in the chaos and confrontation, was a sea of raised fists and Mexican flags. Not tucked in a pocket or painted on a cheek, but unfurled and waving high, as if daring the city, the country, to see them.

For many, seeing the Mexican flag waved during a protest against Immigration and Customs Enforcement felt like an affront. They asked: If you’re demanding rights in this country, why wave the flag of another?

But that flag is not about rejecting the United States. It’s about refusing to be erased.

It’s about asking if American identity can contain this kind of complexity, or is belonging still tethered to silence, assimilation and erasure of difference?

Los Angeles is the perfect place to ask this question because Mexican identity isn’t foreign there. This was Mexico once and remains part of the memory, culture, street names, food and families who never crossed a border because the border crossed them. In this city, the Mexican flag isn’t a symbol of separation or rejection. It’s a claim: We are both.

More than 11 million people of Mexican origin live in California. For many of us, being both and neither isn’t a contradiction. It’s a simple truth.

American pluralism has never been open-armed. It tolerates presence but punishes visibility. Mexican Americans are deemed essential when the country needs labor — in the fields, in hospitals during the COVID pandemic, in our homes, in our schools and in the armed forces — but suspicious when they demand dignity, political voice or pride in where they come from.

So, when people waved the Mexican flag in the streets of L.A., it struck a nerve. But maybe what unsettled people is what it revealed. It raises questions about our complex national identity. Does being American require being less of anything else? Does pride in your roots cancel your claim to this country? Does loving where you are mean forgetting where you’re from?

No one objects when the Irish flag is flown on St. Patrick’s Day. That’s the “right” kind of ethnic pride. But when that same pride surfaces in protest, it suddenly is characterized as unruly and out of place, as if visibility becomes acceptable only when it poses no challenge to the dominant narrative.

The truth is, the presence of the Mexican flag in this country, in this city and in these protests is not only valid; it matters. It speaks to a history too often ignored, to a community too often overlooked. It reminds us that belonging isn’t granted through silence or submission but claimed through presence, memory and voice. |

|

|

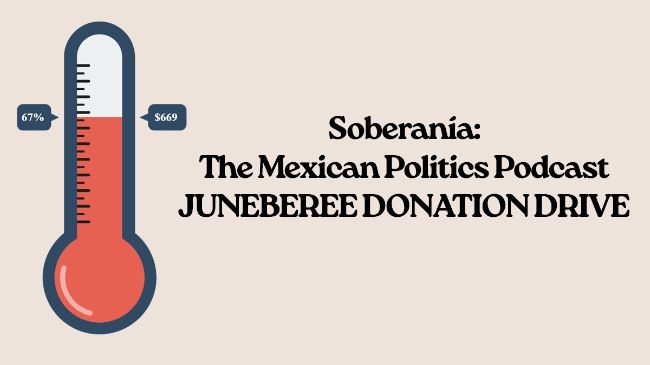

The June Donation Drive is surging ahead! Soberanía: The Mexican Politics Podcast has raised 67% of our goal of $1000USD. If we reach our goal, your support dollars will be matched by a generous anonymous donor! Soberanía is hosted by journalists and Mexico Solidarity Project members José Luis Granados Ceja and Kurt Hackbarth.

All donations go to purchasing equipment for their new sound studio.

Donation info: https://mexicosolidarity.com/soberania/ |

|

Don’t miss an issue! Sign up for a free Mexico Solidarity Bulletin subscription.

For a deeper dive into current news and analysis in English, check out our media website and the podcast ¡Soberanía! (Sovereignty) with José Luis Granados Ceja and Kurt Hackbarth. New episodes will now arrive weekly on Wednesdays, not Tuesdays.

Sin Muros from José Luis and Kurt is a weekly Spanish language Mexican TV show on Canal Once that analyzes Mexico-US relations. It's also on YouTube, with English subtitles.

And those of you with mad skills and/or interests we want to hear from you! Get in touch to find ways to plug in to the work. Drop a line to meizhului@gmail.com. |

|

|

Recent news reports and commentaries, from progressive and mainstream media, |

|

Natascha Elena Uhlmann, Mexican GM Workers to Vote Next Week on Union at Second Plant Labor Notes. If successful, it would be the first time that an independent union represents two assembly plants at one of the Big Three automakers.

Manuel Gonzalez, Una desolación impune Sin Embargo. Minera canadiense extrajo por décadas oro de Guerrero. Ahora solo quiere dejar daños.

María Josefina Arce, With concrete actions Mexico will arrive at the Women's Conference Radio Habana. Concrete actions also include the recognition of agrarian rights for at least 150,000 women, given the existing inequality in land tenure between men and women, given that only 27% of rural women have their rights recognized.

Gerardo Hernández, Jornada laboral de 40 horas: Sindicatos proponen aplicación de la reforma en dos años El Economista. Tereso Medina, secretario general adjunto de la Confederación de Trabajadores (CTM), aseguró la organización apoya una reducción paulatina de la jornada laboral, pero no comparten la meta para el 2030, sino alcanzarla en un periodo de dos años, además de la creación de una prima sabatina.

Counterinsurgency or Sovereignty Loss? Crenshaw’s Tactic to Fight Mexican Drug Cartels, Reform Austin. Hard-right figures in Trump’s government see the Sheinbaum administration as more open to its lunatic counterinsurgency dreams, bringing up memories of the bloody results of Plan Colombia.

Ante conflicto en Medio Oriente, ONU debe llamar a la paz: CSP La Jornada. El año pasado, el gobierno mexicano respaldó su compromiso con la paz al intervenir en la investigación de la Corte Internacional de Justicia sobre el genocidio de palestinos por parte de Israel; este año, tópicos sobre que Israel y Estados Unidos atacan ilegalmente a Irán y tratan de quemar el mundo.

Fabiola Sánchez, First face-to-face between the leaders of US and Mexico will have to wait The Associated Press. Michael Shifter, adjunct professor of Latin American Politics at Georgetown University, said that while the canceled Trump meeting was a loss, Sheinbaum’s other bilateral meetings with leaders from India, Germany and Canada should not be discounted.

Camila Ayala Espinosa, OIT exhibe que en México se trabaja sin vida ni descanso, más que nadie en la OCDE Proceso. Los mexicanos trabajan, en promedio, un 96.6 por ciento más horas que los empleados del resto de los países miembros de la OCDE.

Jorge Antonio Rocha, Mexico to investigate death of Mexican immigrant while in ICE custody Aztec Reports. This marks the first reported case of a Mexican immigrant dying in ICE custody since President Trump relaunched his long-standing immigration crackdown.

Alberto Aguirre, La insolvencia de CAME y otros chanchullos de Sofipos La Política Online. El gobierno de México debe contarse entre los afectados por la declaratoria de insolvencia financiera decretada respecto de CAME. |

|

|

|

|

The Mexico Solidarity Project brings together activists from various socialist and left organizations and individuals committed to worker and global justice. We see the 2018 election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as president of Mexico as a watershed moment. AMLO and his progressive Morena party aim to end generations of corruption, impoverishment, and subservience to US interests. Our Project supports not just Morena, but all Mexicans struggling for basic rights, and opposes US efforts to undermine organizing and Mexico’s national sovereignty.

Editorial committee: Meizhu Lui, Bruce Hobson, Agatha Hinman, Victoria Hamlin, Courtney Childs, Pedro Gellert. To give feedback or get involved yourself, please email us! |

|

Subscribe! Get the Mexico Solidarity Bulletin in your email box every week. |

|

Web page and application support for the Mexico Solidarity Project from NOVA Web Development, a democratically run, worker-owned and operated cooperative focused on developing free software tools for progressive organizations. |