|

|

The weekly newsletter of the Mexico Solidarity Project |

|

Every issue archived online at mexicosolidarityproject.org/archives/ |

|

November 26, 2025 |

|

|

|

Tren Maya on the Tracks of History |

|

Meizhu Lui, for the editorial team |

|

|

Tren Maya, 2024 |

|

In 1966, traffic was terrible in Honolulu, Hawaii. The mayor said, “Taken in the mass, the automobile is a noxious mechanism whose destiny in workaday urban use is to frustrate man and make dead certain that he approaches his daily occupation unhappy and inefficient.” Mayor Blaisdell proposed a light rail system to alleviate people’s frustration.

Nearly 50 years later, in 2011, the first shovel hit the ground. They planned three segments going 18.9 miles, or 30.4 km, in and around the city. But construction was delayed. Native Hawaiian suits charged that the route would disturb the bones of their elders, environmental impacts had to be studied, and more delays occurred after they discovered sub-par welding and cracks. Segment 1 finally opened in 2023 and Segment 2 in 2025. Segment 3 won’t be ready until 2031.

Mexico’s Maya Train goes about 932 miles, or 1500 km — 47 times longer than Honolulu’s rail. Lopez Obrador proposed it in 2018 when he ran for president. Construction began in 2019, and it was ready to ride in 2024.

The train still has many detractors — particularly outside of Mexico. Unlike most who have written about the train, British researcher Etienne von Bertrab has closely followed the suspenseful adventure: how huge physical and political obstacles were confronted, how the plot and subplots twisted and turned, how thousands of humans, animals and plants were involved. The train project never traveled a straight line.

To make the story of this remarkable achievement accessible to all, von Bertrab put his findings into graphic novel form, the just-released Más Allá, which means “beyond.” President López Obrador wanted Tren Maya to be the signature project of his presidency. It goes beyond that. It’s one for the history books — and graphic novels! |

|

|

Tren Maya: Militarization of Mexico? |

|

|

Étienne von Bertrab, born and raised in Mexico, now teaches political ecology at University College London. His research focuses on environmental (in)justice in Latin America. Over the last five years, von Bertrab has led a team conducting research on the Tren Maya, the López Obrador administration’s flagship infrastructure/development project. His team has paid particular attention to the voices of people living in the southern region. He turned his research into the recently released graphic novel, Más Allá: Una Historia del Tren Maya, |

|

|

Since this is such an important topic, we are publishing the interview in two parts. Tune in for Part 2 next week!

What were the questions that guided your research?

From the very beginning, Mexico’s political opposition was against the building of the Tren Maya, particularly once it became clear that it was AMLO’s signature project. Coming himself from Southern Mexico, the country’s poorest region, he wanted to promote economic development not based on the top-down neoliberal model but to ensure ordinary people actually benefitted.

His opponents did everything they could to stop the project as a way to discredit AMLO and the Fourth Transformation. More than 50 amparos — injunctions — were filed to stop construction, most of them promoted or financed by the political right. It’s incredible that the Tren Maya was actually built, given all the obstacles thrown against it! |

|

|

Existing train tracks across the Peninsula are being upgraded to make way for the Maya Train: Photo: Carlos Rosado Van Der Gracht/Yucatan Magazine |

|

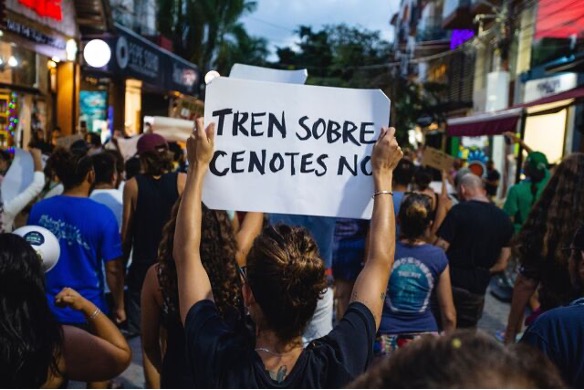

Others raised legitimate questions too, including people living along the proposed route, especially once construction got under way in 2021. These were about the role of the Mexican Secretariat of National Defense, known as SEDENA, potential environmental damages, and the effect on local communities, particularly ejidos. Ejidos are a form of collective land ownership still very present in the south and southeast regions; would these be disrupted? Other concerns related to whether the Tren Maya would cause a Cancún-style touristification of the broader region. |

|

|

Indigenous women protest the Tren Maya, Chiapas 2018: Johnson Center blog |

|

|

A protest in Playa del Carmen: Photo: Natalia Pescador/Eyepix Group/Shutterstock |

|

I was also interested in understanding Sembrando Vida, or Sowing Life, a national program to reduce rural poverty and environmental degradation, and how it intersected with the Tren Maya project. |

|

Both were launched simultaneously in the southern states at the beginning of AMLO’s administration. Would these interventions weaken or strengthen ejidos and communal life? How could urbanization be guided in a more sustainable and socially just way? Would peasants and local producers benefit from this new transport system? |

|

|

Farmer Victor Poot participates in the Sembrando Vida Program |

|

Many questions to research. But given the levels of disinformation and misinformation in the media nationally and internationally, an overarching goal was to better understand what was happening on the ground. A search for the truth has been central to my work.

You sought access to government officials working on the project; did they attempt to make you put the project in a favourable light?

Many journalists and researchers ignored or made assumptions about the actions and decisions of the National Fund for the Promotion of Tourism, known as FONATUR, which was initially in charge of the project, and other authorities. But to me it was important to take concerns gathered from the ground, as well as our own questions, directly to public officials responsible for different aspects of the Tren Maya, of Sembrando Vida, and of the programs of the Ministry of Agrarian, Territorial and Urban Development, or SEDATU, and the Ministry of the Environment, or SEMARNAT, and others also integral to the project. This meant being very open in our dialogue with them, and we built trust over time. |

|

|

Etienne with Maria Luisa ( Sembrando Vida) and Juan Jacobo Schmitter-Soto (ECOSUR) |

|

|

Etienne with Roman Coh, La Reserva de la Bisofera Sian Ka’an (Chunyaxché) |

|

I was pleasantly surprised that most public officials showed a profound spirit of public service, worked very long hours, and were open to debate and criticism, something that was portrayed very differently in the media and in academic circles. And no, we were never pressured, not even by insinuation, to record things in a favorable light.

But of course, my research didn’t just rely on their voices. My work, often together with colleagues and students with whom I travelled every year, involved research at the level of communities, from peasant farmers and ejidatarios to residents of towns and peripheral areas of cities, to the workers. It was these grassroots voices that convinced me that the project was putting into practice AMLO’s rejection of the neoliberal extractive model, instead prioritizing the people and responding to their concerns. We heard many people say the government was treating them differently, with their voices now being heard.

Several times, major changes in the train route or the placement of stations were made due to various reasons, including public opposition. Some critics say that it’s wrong that stations weren’t placed all the way into the city centers, which had been the original plan. But this was not only complicated to do in dense urban areas but, in some cases, it was opposed by residents who would need to be relocated. Instead, for instance, in San Francisco de Campeche, they built a station on the city periphery and implemented a transport system to connect the station to the city and to the airport. For mostly technical reasons, this also happened in Mérida, but the station is connected to the city through an electric bus system that also serves other areas of the city. |

|

|

The old Merida station was not used. The new Tren Maya station was built in Teya, a nearby community. Photo: especial |

|

When the original railway crossing part of the peninsula was built in the 1950s, the government was supposed to pay communities and ejidos for the land they expropriated to ensure right of way for the train. But often people, especially ejidos, weren’t paid. This happened as well when constructing roads and highways. AMLO’s government made good on these old debts and gained their trust. We witnessed many instances of dialogue between communities and the companies building the railway or authorities. These were fascinating processes.

The Tren Maya has often been cited as a major example of the "militarization" of Mexico including its civic sector. What did you find?

The project was first in the hands of the FONATUR, with SEDENA’s Army Corps of Engineers only in charge of the construction of some railway segments. But the Covid-19 pandemic, the amparos and other factors slowed construction, and AMLO clearly got frustrated as he’d promised to deliver Tren Maya before he left office in 2024. In early 2022, he appointed new leaders to FONATUR and formally expanded the role of SEDENA. |

|

|

First Tren Maya coach delivered: Railway Gazette |

|

It would not only oversee the project but also run the operation of the train. Similarly, SEDENA was given responsibility for the operation of the new airports in the region and the publicly owned Mexicana airline. State companies were created to operate these infrastructures and services, all under SEDENA. |

|

Critics refer to this as “militarization,” which has, of course, a negative connotation. The reality is that, as in previous governments, AMLO used the armed forces to deliver his political project — to move away from neoliberalism and ensure these public services wouldn’t be privatized in the future. We remember what happened in the 1990s, when Mexico’s railway network was privatized and we lost all our passenger trains. But more fundamentally, he decided to use the military for different purposes than in the past, when they were central to repressing dissenting movements. His use of the military is constitutional. One of the military’s functions is to “support the development of the country.” He made sure this was the case under the Fourth Transformation.

AMLO had other reasons for deciding to give the operation of the Tren Maya to the military. I discuss them in my book Más Allá: Una Historia del Tren Maya! This includes the question of what to do with around 300,000 armed forces personnel. If they won’t be used to repress dissent and there’s no chance we could stop a US invasion militarily, what should the country ask them to do to keep them busy? Give them work on public infrastructure projects! Apart, of course, from their role in disaster response and public security, needed to counter the organized crime violence that we inherited from Felipe Calderón’s infamous “war against cartels.”

The National Guard present in the region reinforces the government’s public security strategy. They are deployed in the Tren Maya stations and on the trains, not with weapons, but as station managers, keeping people clear of the rails and answering passenger questions. |

|

|

National Guard and civilians help those who need it |

|

You see them helping people in wheelchairs and lifting baggage onto the cars. From the friendly exchanges, it’s clear that people appreciate their presence. This completely contradicts the narratives around the “military train.”

When people in the UK or Europe — and certainly in the US — express concern for “Mexico’s militarization,” I laugh. European countries have accepted Trump’s demands to increase their military spending in the next decade at a huge social cost. And this spending is for weapons of war and death! Mexico, on the other hand, isn’t buying missiles, tanks, bombs, surveillance systems and certainly not nukes. During AMLO and Sheinbaum’s presidencies, the military has not been used once for repression or to stop protests. SEDENA’s budget has increased over the last few years because it is building railways and major infrastructure projects.

If this is “militarization,” it’s a different kind of militarism that benefits the common people. |

|

|

|

|

The Gen Z March — or Something Else? |

|

This article by Montserrat Antúnez originally appeared in the November 16, 2025 edition of Sin Embargo.

Mexico City. It was a gathering of old acquaintances: men and women dressed in white and wearing Panama hats, promoters of the Pink Wave movement who supported Xóchitl Gálvez before she was soundly defeated in the 2024 elections, and former officials seeking to create a new right-wing party.

The so-called Generation Z mobilization on Saturday, November 15, where young people appeared only in dribs and drabs, devolved into violence in Mexico City. The march brought together thousands of people critical of President Claudia Sheinbaum’s administration and pitted adults opposed only to Morena against young people actively rejecting the entire political class, including Morena, PRI, PAN and Movimiento Ciudadano.

In front of the Angel of Independence, on Paseo de la Reforma, a group of elderly men and women shouted at three young people putting on black bandanas to cover part of their faces: “Out! Out! No masked people!” Even before the march began, differences were clear.

The first contingents in the march included people from Michoacán, where recently Carlos Manzo, the mayor of Uruapan, was murdered, and the demand for public officials to sever ties with drug trafficking echoed throughout the march. A man from Morelia, Michoacán, joined the call for justice for the mayor’s murder, asserting, “I just want security.” One young woman insisted on distancing herself from all political parties. “We’re not with any of them; we’re marching because we’re fed up with the violence,” she said.

But was this self-proclaimed Generation Z march really representing youth? In fact, the march was mainly characterized by the participation of right-wing opposition politicians and former officials, who seized on the murder of Carlos Manzo to call for justice and protests in cities throughout Mexico. They spread the message of anger through networks of paid trolls and bots, generating videos and right-wing online content.

Some of the many right-wingers promoting the marches were former PAN president Vicente Fox and Emilio Álvarez Icaza and Guadalupe Acosta Naranjo from the defunct Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD), who are now seeking to create a new party. And Arturo Herrera, who supports on social media Ricardo Salinas Pliego, the businessman who called the president a “narco-president” from his X account. He was enraged because the Supreme Court recently ordered him to pay millions of pesos in taxes. The list of prominent right-wingers who participated goes on and on.

But as the march moved toward the Zócalo, criticisms from onlookers could also be heard. “This is the Pink Wave!” accused a woman who responded to each of the protesters' slogans with the phrase “Long live my president!” |

|

|

|

Recent news reports and commentaries, from progressive and mainstream media, |

|

Pablo Meriguet, Gen-Z protests in Mexico or coordinated chaos? People’s Dispatch. The executive branch has denounced the recent anti-government demonstrations in Mexico and questioned what actors may really be behind the so-called youth uprising.

Sandra Rojas, “La vida no es solo trabajar”: por qué las 40 horas no pueden esperar La Cadera de Eva. El Frente Nacional por las 40 horas cumple dos años con movilizaciones en todo el país para exigir la reducción inmediata de la jornada laboral, en un contexto donde México es el país que más trabaja en la OCDE.

David Bacon, Poverty and Deportees on the Streets in Tijuana Dollars & Sense. In the U.S. media, even in progressive media, we pay very little attention to what happens to most people when they’re deported, or when they choose self-deportation as a result of fear.

Aníbal García Fernández, La élite, la derecha y la lucha de clases Revista Contralínea. En México, el 1 por ciento más rico de la población percibe ingresos 442 veces superiores al 10 por ciento más pobre. Los 14 multimillonarios –entre ellos, Carlos Slim, German Larrea y María Asunción Aramburuzabala– concentran el 8 por ciento de la riqueza nacional. La desigualdad que eso ha generado llevó a la mayoría a elegir un cambio en las urnas en 2018, y ratificarlo en 2024.

Natascha Elena Uhlmann, We Can’t Bridge the U.S.-Mexico Wage Gap Without Supporting Organizing in Mexico Labor Notes. In order to jointly formulate language and recommendations, the UAW is calling for the convening of a tri-national labor council of unions in strategic sectors. This will require speedy action from unions in all three countries, and a willingness to come together despite disagreements over issues like tariffs, which the UAW has backed.

Renata Aguilar, Desgaste acelerado de la clase obrera en la industria automotriz Resumen LatinoAmericano. los y las trabajadoras al interior de las fábricas no son meros accidentes, son parte inherente del proceso de acumulación capitalista.

Jalisco New Generation Cartel Is Linked to Uruapan Mayor Killing in Mexico Telesur. Arrests, phone data and surveillance footage point to coordinated attack during Day of the Dead festivities.

Emilia Reed, La bandera pirata desembarca en México Granma. La derecha aprendió tempranamente que la batalla por el poder pasa por apropiarse de los códigos culturales juveniles.

Wyatt Reed & Kit Klarenberg, Mexico’s ‘Gen Z rebellion’ exposed as viral right-wing plot The Grayzone. Presented as a spontaneous youth-led uprising against corruption, violent protests that erupted across Mexico this month were backed by local oligarchs and an international right-wing network determined to topple the popular President Claudia Sheinbaum.

|

|

|

|

|

The Mexico Solidarity Project brings together activists from various socialist and left organizations and individuals committed to worker and global justice. We see the 2018 election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as president of Mexico as a watershed moment. AMLO and his progressive Morena party aim to end generations of corruption, impoverishment, and subservience to US interests. Our Project supports not just Morena, but all Mexicans struggling for basic rights, and opposes US efforts to undermine organizing and Mexico’s national sovereignty.

Editorial committee: Meizhu Lui, Bruce Hobson, Agatha Hinman, Victoria Hamlin, Courtney Childs, Pedro Gellert. To give feedback or get involved yourself, please email us! |

|

Subscribe! Get the Mexico Solidarity Bulletin in your email box every week. |

|

Web page and application support for the Mexico Solidarity Project from NOVA Web Development, a democratically run, worker-owned and operated cooperative focused on developing free software tools for progressive organizations. |