|

|

The weekly newsletter of the Mexico Solidarity Project |

|

Every issue archived online at mexicosolidarityproject.org |

|

November 27, 2024 |

|

|

|

Turning on the Tap — of Compassion |

|

Because Trump, the incoming US president, has generated so much hostility toward migrants, we're rerunning our 2022 interview with Todd Miller, who encourages us to deepen our understanding of where borders lie. —Meizhu Lui, for the editorial team |

|

|

“We have Coca-Cola, Pepsi-Cola, RC Cola, every kind of Cola,” a woman from the global South fumed way back at the 1995 Beijing Women’s Conference, “but there’s no water coming from the tap!”

In México, more than one drought has stopped the flow of our world’s most essential liquid — and residents demanding adequate water have regularly come up dry. Coca-Cola, meanwhile, never seems to see shortages and goes on merrily converting water from a life-giving element into a drink that invites, among other maladies, life-threatening diabetes.

Climate change is speeding up the rates we experience droughts, hurricanes, and temperature spikes. Events once considered occasional natural disasters have become increasingly common unnatural disasters. People are abandoning areas where water has either stopped flowing or started inundating their homes.

And those of us living in abundance and safety, what do we do when those people start showing up near our homes as migrants? Todd Miller, our Voices interview spotlight this week, first confronted that question when he ran into a migrant in the Arizona desert desperately in need of water. Miller initially hesitated. What walls have we erected in our own hearts, he reflects, that we see reproduced at our national borders? And, conversely, what border policies have us — as individuals — stifling the urge to help others?

Who gets access to a decent life depends on whether we prioritize people’s lives or Coke’s profits. Making the right choice requires us to break up the barriers in our hearts and our policies that dry up the flow of human compassion. Turn on the tap! We need that compassion flowing now more than ever.

UPDATE: Just last week, president Sheinbaum unveiled a new program reforming how water is distributed. Meeting the people's needs will come first. |

|

For a deeper dive into current news and analysis in English, check out our media website. And definitely see the new English podcast ¡Soberanía! (Sovereignty) with José Luis Granados Ceja and Kurt Hackbarth. They entertain, while dismantling the lies and distortions about Mexico fed to us by the mainstream media. |

|

Don’t miss an issue! Sign up for a free Mexico Solidarity Bulletin subscription. |

|

|

Where Do the Borders in Our Own Hearts Lie? |

|

Todd Miller, a journalist based in Tucson, Arizona, who’s also lived in Oaxaca, has written widely about border and immigration issues. His books have examined issues ranging from militarization and the US Border Patrol to climate migration and the expansion of “border” into a global North-South division. His most recent book, Bridges Not Borders, offers an unexpectedly hopeful vision. You can follow Miller’s work weekly at The Border Chronicle. |

|

|

Most people think of the US border as a “wall” that keeps Mexican and Latin American migrants from crossing into “our” land. What does “border” mean to you?

“Protecting territory” regularly gets presented as the only way to understand “border.” But the border actually turns out to be less about land and more about protecting a global system that benefits US corporate and political elites. In this unsustainable system, the tentacles of US power reach into other countries, suck out their wealth, and become a huge contributing factor to displacement, dispossession, and even ecological catastrophe.

The border that separates global North and South has turned into the front line of a war, not an overt war — this war’s death and destruction seldom make headlines — but an invisible war against the poor.

In your book Storming the Wall: Climate Change, Migration, and Homeland Security, you predict that climate-driven migration will pick up speed and become the major issue for our time. Is border policy changing to get ready for this phenomenon? |

|

I used to see a climate crisis as a problem somewhere in the future. But that crisis has arrived, and it’s been building. Climate change does manifest itself differently from economic crises, but the two get cut from the same cloth. |

|

|

Photo: FreshFruitPortal |

|

The US military apparatus, interestingly, has not put climate issues into the abstract future. Military planning looks 25 years ahead.

In the 1990s, the Pentagon was already talking about climate change, and a 2003 Pentagon report concluded fortresses would be needed to keep out “unwanted starving immigrants.”

That same year saw the U.S. Department of Homeland Security created, ostensibly due to the September 11 attack. But other factors were also likely weighing on military minds. In 2010, Obama linked climate change to national security and mandated that Homeland Security look explicitly at climate-related mass migrations. A 2021 Pentagon document on the climate threat mentions migration 18 times.

Climate migration has already become huge, with 1.2 million people displaced from Guatemala and Honduras in 2020 alone. In the Central American dry corridor — an area now particularly susceptible to drought — the number of people suffering from hunger has jumped from 2.4 million in 2018 to more than 8 million by the end of 2020, according to a World Food Programme report.

Our world’s richest countries can somewhat withstand climate disasters, but, even in a nation as rich as the US, poor people will be at great risk of displacement. This could create issues between states. During the Great Depression, remember, California put up at the state border a “bum blockade.” Could this happen again?

Has having children yourself increased your sense of urgency about addressing climate migration fairly?

My grandmother comes from Marinduque Island in the Philippines, a place that faces rising sea levels. I’ve traveled there. I’ve seen a house with waves lapping on it. I felt like I was seeing a corpse. |

|

I saw a man walking with his child and wondered whether that child will be able to grow up on this island. I look at my own children, and I wonder what kind of world will they live in. |

|

|

Alfredo Estrella/Agence France-Presse. Getty Images |

|

So, yes, I feel more urgency. But — simultaneously and paradoxically — we need to slow down. We need less anxiety and more heartfelt concern. We need to take the time to develop relationships, bonds of solidarity, with people living in endangered places. We can ask ourselves where the borders in our own hearts lie — and then move to take those borders down.

Your thinking about borders draws on US abolitionist traditions. Can you explain why?

The writing of Ruth Wilson Gilmore on prison abolition has affected me profoundly. She notes that 1 percent of “abolitionism” speaks to getting rid of prisons and 99 percent to building a world of justice. We can apply abolitionist principles when we do cross-border organizing to address migration. Only a small percent of our work needs be at the border itself. The rest should address fulfilling people’s needs where they currently live, the key to solving the challenges migrations create.

Look at the $400 billion spent on border and immigration enforcement since the Department of Homeland Security started up in 2002 — the drones, the surveillance towers, the prisons, the armed personnel. With this perspective in mind, we need to push to “defund the border.” Instead of militarizing the border, we should be focusing our nation’s attention and money on the cause of border insecurity: human insecurity.

Many in the US, you’ve noted, are suffering from “wall sickness.” How can we stop that contagion? |

|

Wall sickness begins with fear. In my experience with Trump supporters, some fear losing their jobs, and that fear can turn into hate as “others” get blamed for their own, well, insecurity. Meeting those “others” person to person — including Trump supporters — can be transformative. We need to find and create spaces where those meet-ups can happen. The borderlands could be such a place. |

|

|

What our elites fear most: the human bond that makes people want to take down the walls and stop the invisible war between the global North and South.

When we live in a psychological bubble, with walls around our minds and hearts, we obstruct how we think and feel. Once we exit that bubble, there’s no going back. |

|

|

|

|

Reynaldo Rivera, In a Flash |

|

|

Activist Vicky Hamlin, a retired tradeswoman, shop steward, and painter, shines the light — in her art and in this column — on the lives of working people and the world they live in. |

|

|

Throughout the 1980s and 90s, Reynaldo Rivera photographed the life he knew, in house parties, drag bars, of performers, of trans loved ones, and the Echo Park neighborhood of LA. He has since exhibited his work nationally, including at Reena Spauling Gallery, Los Angeles (2019), at PS 1 in New York City and has been published in Granta. In 2020, Semiotext(e) published a monograph of his work, Reynaldo Rivera: Provisional Notes for a Disappeared City. |

|

|

Every time someone drags out their cellphone to “just let me show you a picture!” I cringe a little, hoping they won’t find it in the hundreds of snapshots they carry around. These days, everyone is a photographer. Selfies, food, pets, dates, family, and so on. So it takes something special to capture our attention. |

|

|

|

|

Martine (Herminia) and Reynaldo Rivera. 1981. Silver gelatin print. Courtesy the artist, PS 1 |

|

|

|

What is that something special? Yes, it’s partly the subject, partly the newness or trendiness. But something about a real photographer’s eye goes beyond what the photograph is “about." |

|

|

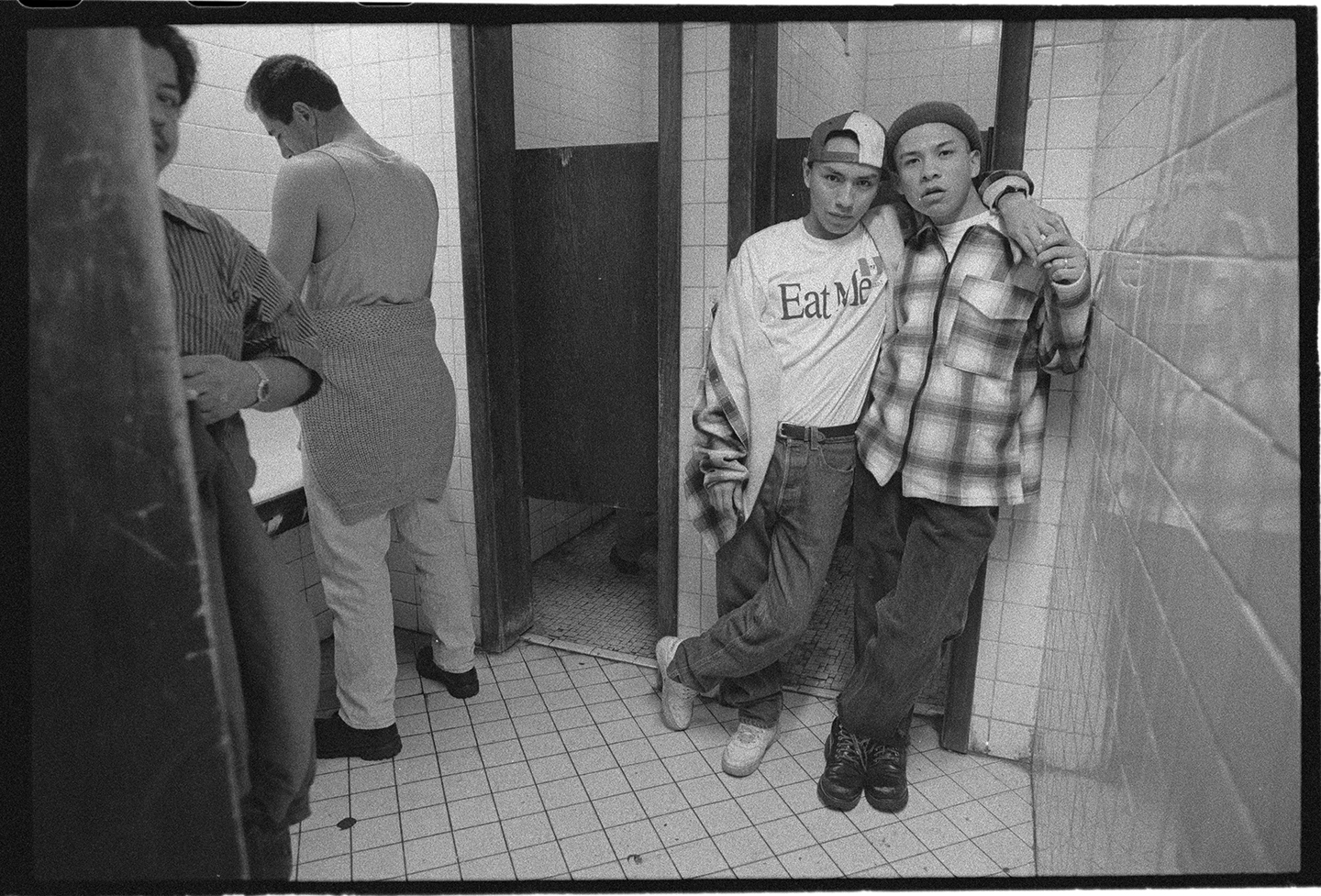

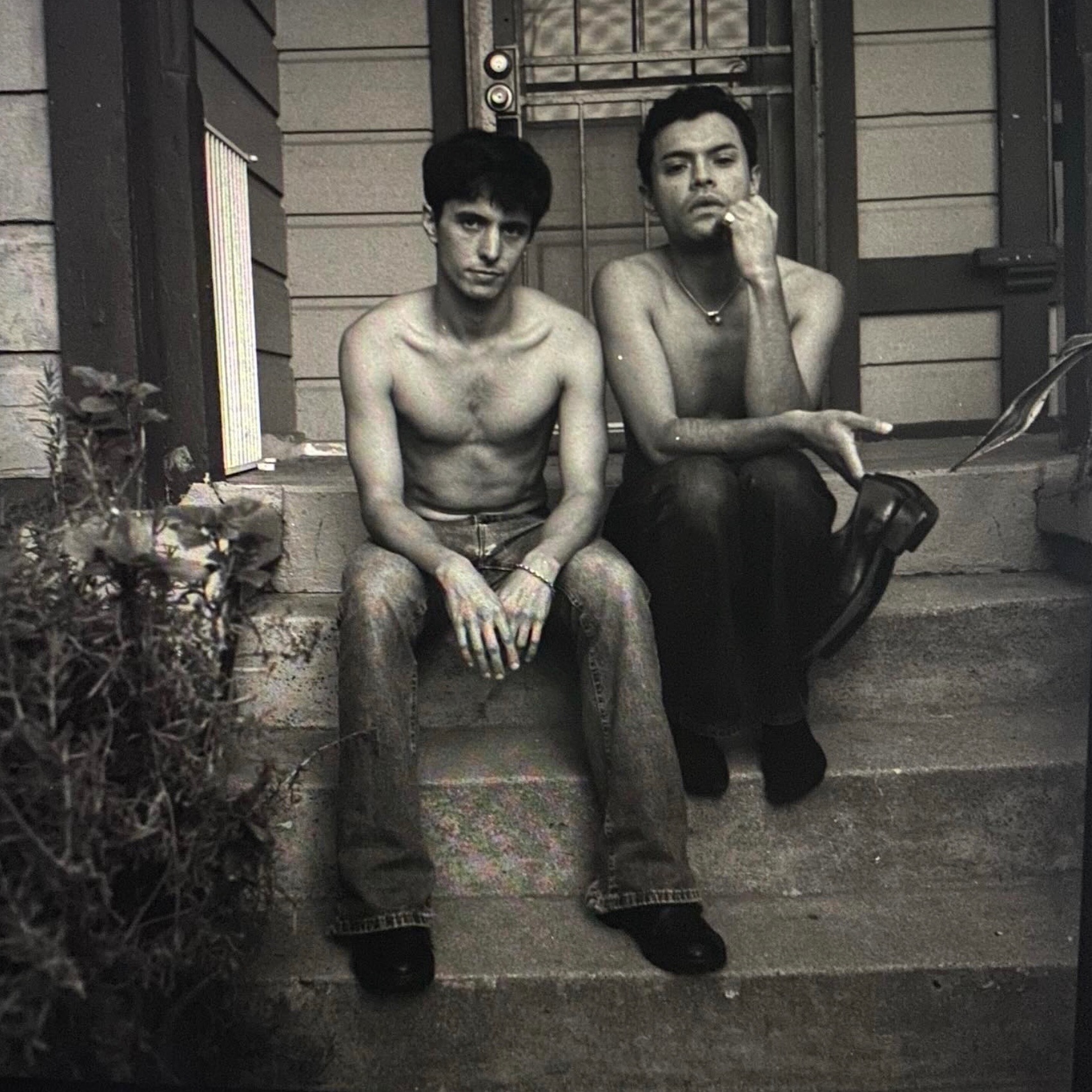

Wes Cutter, Echo Park, 1992 |

|

Photography is quick, even in a studio, the moment of creation is a flash. So you have to think fast, especially in moving scenes. I think photography is about time — the here and now and the long view. You can capture movement with blurred edges, change the lighting, gestures of movement. |

|

|

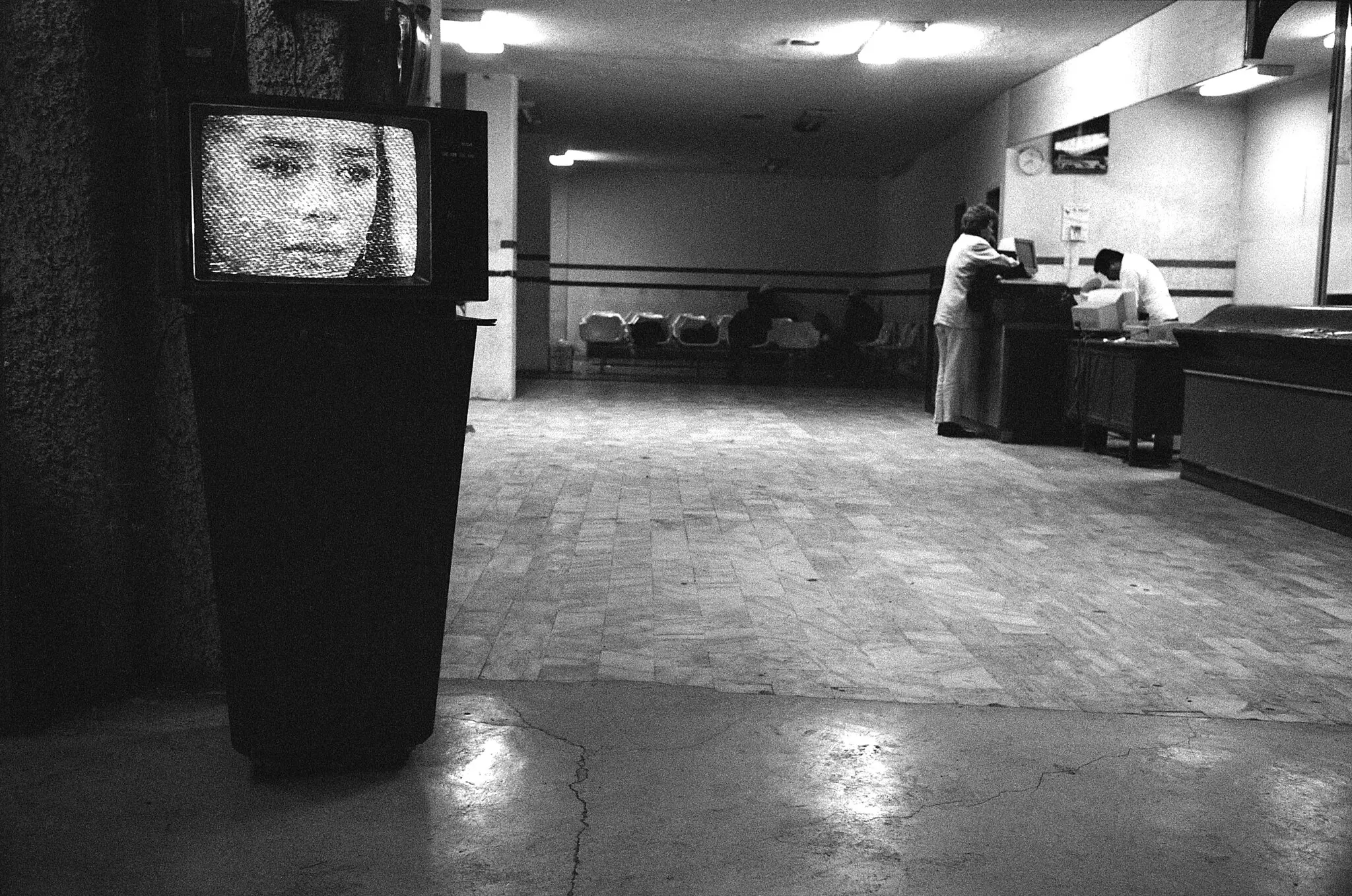

La Plaza, 1997 |

|

But time is also part of the backstory; time suggests growth, rebirth, failure, struggle — things evolve. |

|

“My life was constant movement, and photography allowed me to freeze certain moments.” Reynaldo Rivera in NYC MOMA Magazine, 2024, Reynaldo Rivera, Lauren Mackler, Karl Rittenbach |

|

|

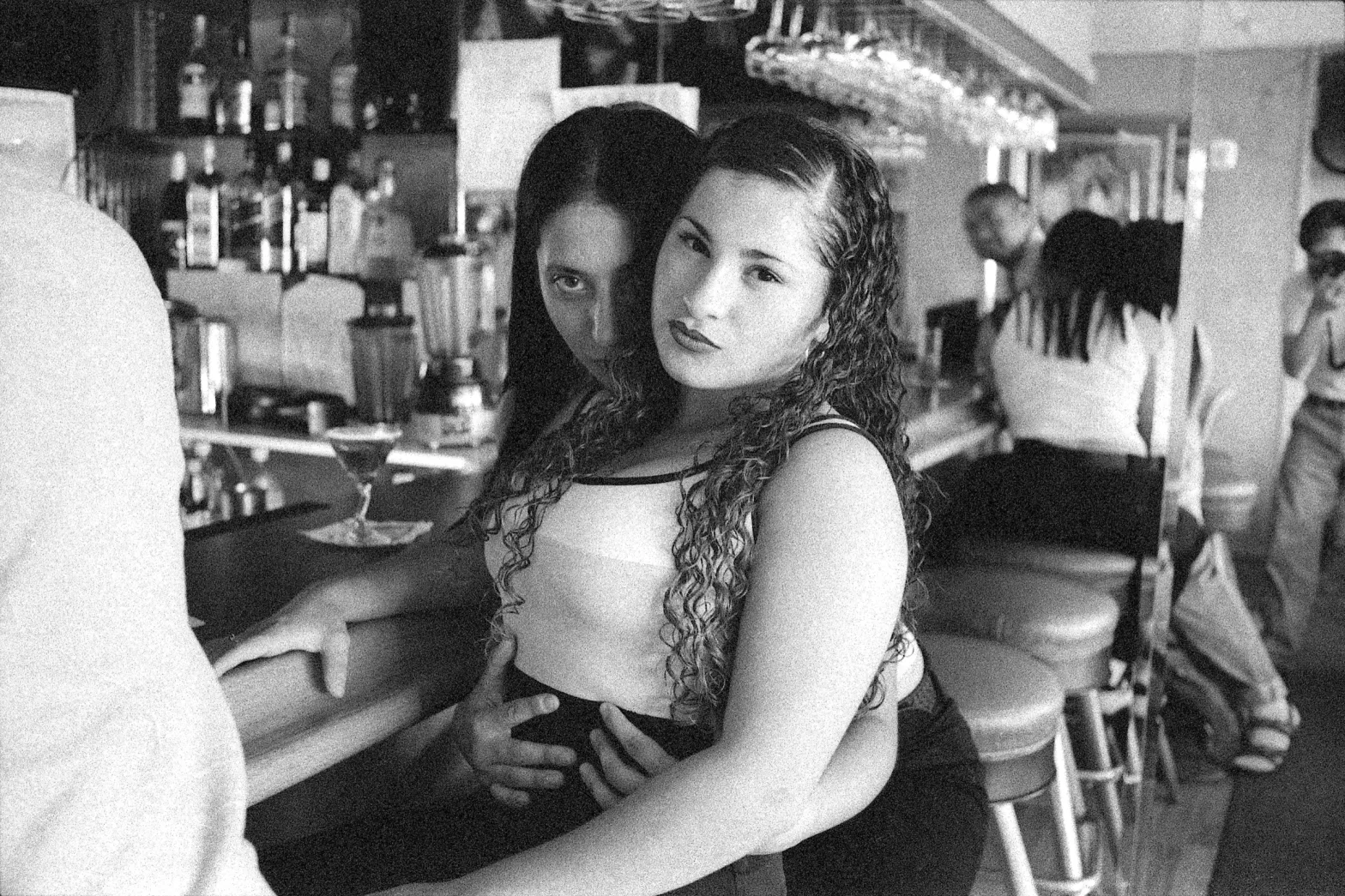

Girls, El Conquistador, 1997 |

|

When someone like Reynaldo Rivera comes along, he combines these things with his sensitivity to his subject and shows us that specialness. This is a specialness that is not about selfies but about art. I’m not sure he would agree with me about selfies, because he did start out with Polaroid selfies, but he sees light and shadow, shapes, composition, direction of flow, all in a second, with a real eye to what those elements are for — to tell the backstory. To talk about life. |

|

|

the Stoop, 2024 Instagram |

|

|

Bianco, 1992/1923 |

|

One of my favorites is an older photo, Bus Stop, Sonora. 1991. It is so unassuming, so much empty space, such a utilitarian location. But the TV tells a story all on its own, of another life. Reality, or the present, can change, and does. Past, present, future. |

|

|

Bus Stop, Sonora 1991 |

|

Reynaldo Rivera brings us around full circle. That's life. |

|

|

|

|

Recent news reports and commentaries, from progressive and mainstream media, |

|

Juan David Rojas, With Trump in the White House, Can Mexico Avoid Making the Drug War even Bloodier? The Nation. Whether the US intelligence agencies which depend on Mexico as a key hub for the drug trade they control (and which provides substantial off-book funding for US imperialist crimes worldwide) would allow an actual solution of the Drug Question is not answered by this article.

Kau Sirenio, ¿Estamos preparados para recibir a los migrantes deportados y retornados? Pie de Página. En Estado Unidos, los empleadores explotan a los migrantes todos los días; como no cotizan en el seguro no tienen derecho a servicio medico; y cuando no pueden trabajar, son abandonados hasta por su propia familia.

Andrea Lobo, The AFL-CIA’s Solidarity Center expands operations in Latin America WSWS. The article contains a look at some fo the details of US and Canadian labour’s dealings in Mexico, in the author’s view, “the campaign for US-trained independent unions has frequently served to simply smoke out and fire the most militant workers.”

Carlos Fernandez-Vega, Plan Nacional Hídrico La Jornada. La presidenta Sheinbaum presentó su Plan Nacional Hídrico en el que subraya que el acceso al agua es un derecho humano de los mexicanos y un bien de la nación, no una mercancía como intentó convertirla el régimen neoliberal en su despiadado proceso privatizador.

Pietro Straulino-Rodriguez and Natalia Merino Moreno, Status of Mexico President Claudia Sheinbaum’s Labor and Employment Bills During Her First 100 Days in Office Ogletree Deakins. Significant labor and employment–related legislation under consideration include bills addressing workweek reduction; an increase in the Christmas bonus; classification of app-based couriers as employees; a minimum wage increase; and an amendment that would prescribe certain rest periods and working conditions.

Adriana Urrea, Nuevo sindicalismo corporativista amenaza unidad obrera en México Amexi. El presidente colegiado de la UNT, Francisco Hernández Juárez, destacó la importancia de la unidad en el sindicalismo democrático para defender los derechos laborales y enfrentar nuevas amenazas en el panorama laboral mexicano.

Elías Camhaji, The first battle: Claudia Sheinbaum moves against Trump’s immigration policy El País. The president has activated her Cabinet, marking territory on one of the crucial fronts of the bilateral relationship and sending messages that challenge the Republican’s proposal to deport a million people each year.

Hector Alejandro Quintanar, La Revolución mexicana y la recuperación del nacionalismo Sin Embargo. Desde 2018, la reivindicación de la Revolución Mexicana es también una práctica anual, no sólo al afirmar un desfile el 20 de noviembre sino también al señalarla como un antecedente histórico del proyecto gobernante: la Tercera transformación.

Matt Huber, Why the Rust Belt spurned Bidenomics The New Statesman. The poor showing at the ballot for DNC candidate Kamala Harris and her Popular Front for the Elimination of Palestine has launched a thousand thinkpieces, more than a few of which (finally) look at the class politics and electoral success of Morena, AMLO and Presidenta Claudia Sheinbaum.

Canadá se inclina por mantener T-MEC trilateral, pero no descarta excluir a México La Jornada. Los políticos canadienses, atrapados en batallas internas entre opiniones neoliberales alternas sobre si los inmigrantes o las políticas de cambio climático son responsables de la inflación y el estancamiento económico, ahora intentan convencer a Trump de que México es un caballo de Troya para China. |

|

|

|

|

The Mexico Solidarity Project brings together activists from various socialist and left organizations and individuals committed to worker and global justice. We see the 2018 election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as president of Mexico as a watershed moment. AMLO and his progressive Morena party aim to end generations of corruption, impoverishment, and subservience to US interests. Our Project supports not just Morena, but all Mexicans struggling for basic rights, and opposes US efforts to undermine organizing and Mexico’s national sovereignty.

Editorial committee: Meizhu Lui, Bruce Hobson, Agatha Hinman, Victoria Hamlin, Courtney Childs, Pedro Gellert. To give feedback or get involved yourself, please email us! |

|

Subscribe! Get the Mexico Solidarity Bulletin in your email box every week. |

|

Web page and application support for the Mexico Solidarity Project from NOVA Web Development, a democratically run, worker-owned and operated cooperative focused on developing free software tools for progressive organizations. |