|

|

The weekly newsletter of the Mexico Solidarity Project |

|

Every issue archived online at mexicosolidarityproject.org |

|

October 30, 2024 |

|

|

|

When Tourism Doesn’t Mean Exploitation |

|

Meizhu Lui, for the editorial team |

|

|

Floating down the canal at Sian Ka'an Reserve: photo courtesy of Bucketlist Bri |

|

Like other kinds of migration, tourism has skyrocketed across the globe. While many must travel to escape poverty and violence, many others choose travel to explore all the amazing places on this gorgeous planet.

I said places: mountains, ancient ruins, cities, beaches. In this panorama, though, the people living there are strangely absent to the tourist, blanks in the canvas, not of interest. Adding insult to injury, tourism often forces people who have lived in one place for centuries to migrate to new places far from home.

Take the Yucatán Peninsula, a popular tourist destination. Fancy self-contained resorts in Cancún mean tourists don’t have to see how the people — including the ones serving them — are affected by their pursuit of pleasure. Small farmers and fisherfolk are displaced. Swimming pools guzzle up the water in a dry climate. Ever growing numbers of hotels, cars, noisy airplanes and melatonin-deficient tourists polluting the sea with sunscreen chemicals all upset nature’s balance. Worse, relationships between tourists and service workers mutate into those of master and servant, lacking any sense of human connection.

It doesn’t have to be that way, as Román Caamal Coh explains to us this week. The Mayan people want to share the beauty of their land and contribute to their local economy while doing so. Responsible, community-based tourism sees people as part of the land’s ecology, expanding the visitor's vision. When tourists see a rock or a cenote, they learn that those are part of a larger story about who lived and lives there, what their culture is like and what issues they face. It puts humanity back into travel.

The Yucatán supports 32 Mayan ecotourism cooperatives; they can be booked through Co’ox Mayab*, meaning “Let’s go to the Mayab.” Start packing!

*The Co’ox Mayab cooperative notes: “The first word of our name is spelled with a “k.” We use the letter “c” as our brand to gain rights and commercial use.” |

|

For a deeper dive into current news and analysis in English, check out our media website. And definitely see the new English podcast ¡Soberanía! (Sovereignty) with José Luis Granados Ceja and Kurt Hackbarth. They entertain, while dismantling the lies and distortions about Mexico fed to us by the mainstream media. |

|

Don’t miss an issue! Sign up for a free Mexico Solidarity Bulletin subscription. |

|

|

Mayans Redefine Tourism to Protect The Land |

|

The ecotourism cooperative Community Tours Sian Ka’an in Quintana Roo lies within an ejido, a collectively owned parcel of land. It’s part of a Mayan system of land management dating back centuries and enshrined in Article 27 of the 1917 Constitution. Román Caamal Coh is an ejidatario (member of the leadership structure) and general manager of the cooperative. He talked to Étienne von Bertrab, Meizhu Lui, Bruce Hobson, and Vicky Hamlin on our visit to the cooperative in April. Photos taken on our visit. |

|

|

The ejido encompasses almost 257,000 acres in Quintana Roo — a huge area! How did you use this land?

Mostly, we grew dragonfruit, with yearly sales of many tons. Artisans worked here, and people grew chicle (used in chewing gum and other products) and produced honey. |

|

|

In 1986, UNESCO named part of our land the Biosphere Reserve of Sian Ka’an. Our responsibility is to care for a huge diversity of plants, animals, fish and birds — mangroves, cattails, manatees, crocodiles and pelicans — ensuring their health and that of the Mayan people living here. Biospheres are places where we investigate how to reconcile conserving biodiversity with developing our economy through sustainable use.

Each biosphere reserve is divided into three zones. The core areas are strictly protected — nature simply takes its course here. |

|

Buffer zones surround the core areas, where we allow human activities compatible with ecological practices, including farming and logging but not production like turning the logs into lumber. |

|

The third area is a transitional space where we pursue activities that sustain social structures and cultures as well as the environment. Managing the biosphere led us to investigate economic projects that might benefit our community. That’s what led to the creation of the ecotourism cooperative.

We had the time of our lives on one of your tours with an expert guide — we crossed three lakes, floated on the canal and looked for manatees and crocodiles! How does the cooperative work?

Twenty years ago, community members searching for another economic activity initiated the cooperative. We decided to provide tourists with an experience different from the usual model. |

|

|

In ancient times, Mayans asked the crocodile god in this temple for good luck. |

|

We have several tours to choose from. On boat trips to the lakes, canals and sea, we teach visitors how ancient Mayans interacted with this environment. The narrow canals are natural, with a mild current created by underground river water. The Mayans once traveled them from lake to lake, each lake saltier than the last until you reach the sea.

We explain about the many plants and animals important to the ecology, such as the mangroves that prevent erosion and the oxygen-producing bacteria purifying the air. We require visitors to avoid sunscreen while in the water to prevent its contamination, and we limit the number of tours we do per day. Fresh local foods cooked in the local style are included in the tours. |

|

We have 24 partners in the cooperative, but ecotourism isn’t our only activity — it complements other kinds of work. To avoid overtaxing the resources, we limit the number of tours.

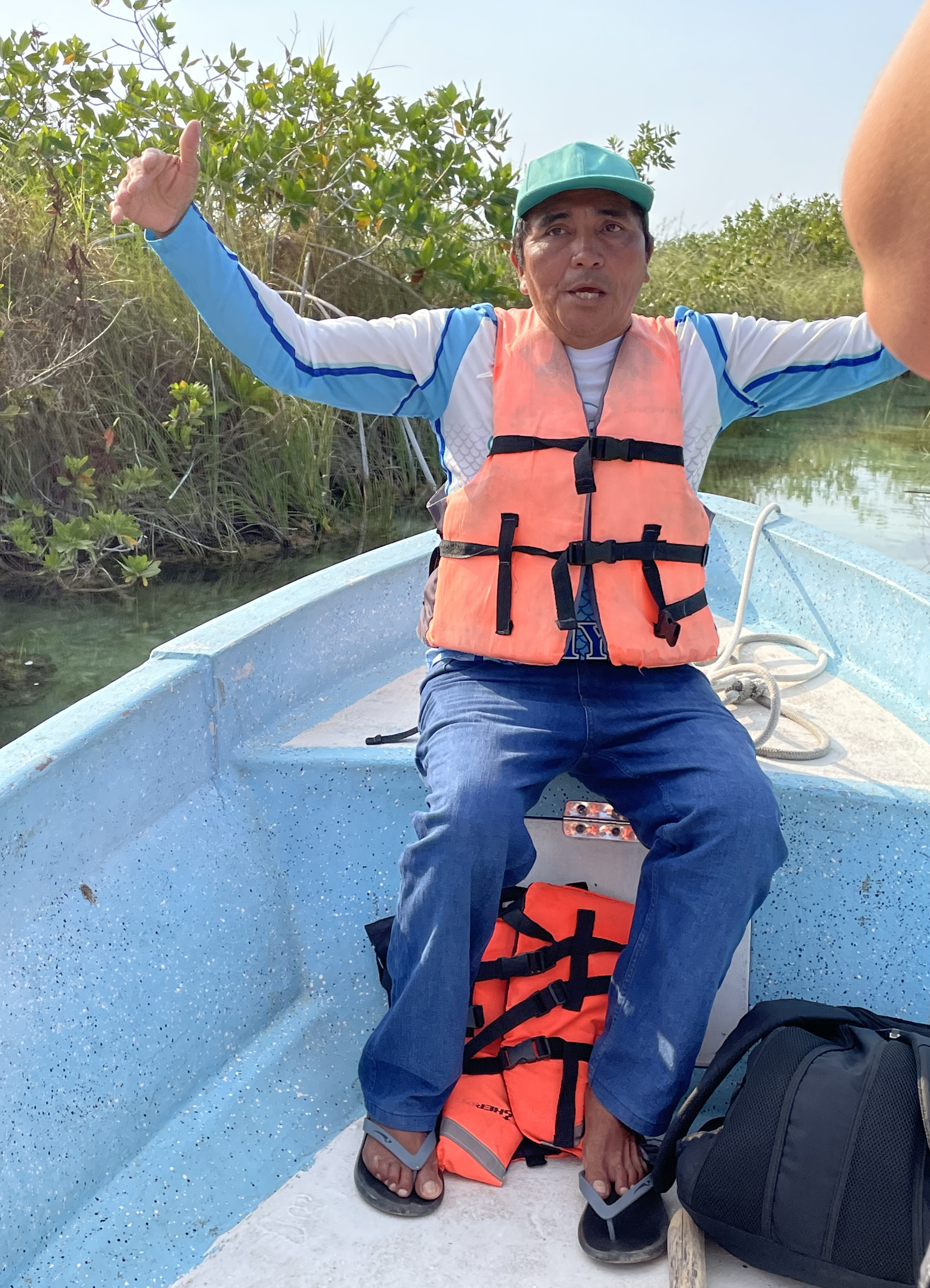

We hire people too. Some cook and serve breakfast and lunch using local products and recipes, and our excellent guides speak various languages. For example, Gilberto, your guide, speaks Spanish, English and French, as well as his native Mayan language. Guides are trained professionals and act as free agents — they don’t have to work for only one tour operation. |

|

|

Gilberto, our multilingual Mayan guide |

|

The government proposed that the Tren Maya go through your ejido and also proposed building the new airport here. What did you think about the government buying a piece of your ejido?

At first, we didn’t want to sell. [ed: Mexico’s 1992 neoliberal reforms allowed the privatization of land and natural resources, including sales of ejido land.] For example, selling meant cutting down some old growth trees. We concluded that we had three options: oppose, agree to their terms, or negotiate.

We negotiated, and they offered a fair price. Still, we came up with 25 conditions, including road repair, new schools, a health center and a hospital. But our number one condition was that we maintain control of the vast buffer zone. We felt we knew best how to steward that land. The terms were agreed to, and we sold 29,650 acres for the airport and 741 acres for the train.

But later we stopped train construction because the government didn’t meet the conditions we agreed to. The situation was very complicated because several government departments were involved — the Secretariat of National Defense, the Office of Tourism and the Department of Agriculture and Urban Planning — and they weren’t well coordinated. |

|

Some of their commitments, like for a new hospital, were probably too ambitious to complete within the original time frame. After our protest, they recommitted to our conditions, and the health center is being built.

Also, when we negotiated with the National Tourism Promotion Fund, they agreed to promote ecotourism with a cooperative near every train station. We don’t want the train to bring more of the usual kind of tourism that benefits big hotel chains and damages our delicate ecosystems. There can be a different kind of tourism that protects nature, keeps Mayans in control and still allows visitors to enjoy it. That’s what we do at Sian Ka’an. |

|

|

Breakfast at Sian Ka’an |

|

What’s in the future?

The train is now here, the airport is here. All that will follow from these projects is not yet clear. The main thing is that we, as a community, must stay vigilant. We will stay organized to protect our land and people, and that is what’s most important. |

|

|

|

|

A National Commitment to Children |

|

Nancy Ortiz is a Mexican journalist who writes a regular column for the online magazine Sentido Común. This article is translated and edited for brevity and clarity for non-Mexican readers. |

|

|

The world is often a hostile place for children.

We live in societies with adult-centric logic. Our hostile and even dangerous social architecture has little place for children; many neighborhoods don’t have safe and public recreational spaces for boys and girls to be active.

Moreover, our whole system of labor fails to consider parenting. In Mexico, the workdays are so long we have little time left for family life. Our parental rights are violated every time women or unions have to bargain over parental leave or time off to care for sick children.

Families too are failing their children. Many families rely on electronic devices as great “allies” to occupy, entertain, and educate. Putting a tablet in front of children is so easy, simple and relatively inexpensive.

But the consequences for children’s development are already visible. Those of us dedicated to the education of children often find they have serious problems communicating because of deficiencies in language development. They may exhibit an inability to pay attention, follow directions or even perform simple physical actions appropriate to their age.

A set of factors are responsible, but an important one is that young people have fewer and fewer opportunities to play. Girls and boys need to play and interact with their peers. They need to experiment, to explore and to have contact with nature. When they play, they learn to face challenges, to communicate their ideas and to get to know the real and tangible world. Manipulating a tablet or playing football in a video game can never be more useful than developing reflexes, fine and gross motor skills, social skills, complex thinking, language and creativity.

The Mexican government has proposed a National Care System that “aims to guarantee access and the right to care by establishing co-responsibility between women, men, families, the community, the market, and the state.” This will be a major step forward. It will help children by alleviating the unpaid care work traditionally carried out by women.

If we can make the National Care System a reality, we can change the current parenting model, reduce working hours and adapt public spaces that offer children the opportunity to play outside the screen.

Society owes it to our children. |

|

|

|

|

Recent news reports and commentaries, from progressive and mainstream media, |

|

Alex Vasquez, Mexico’s Sheinbaum Plans 12% Minimum Wage Hike for Coming Years Bloomberg. Sheinbaum’s goal is to increase the minimum wage until it covers the cost of roughly two and a half basic food baskets.

Roberto Morales, Preocupa a EU inversión de empresas chinas en México El Economista. Los malditos gringos esperan que el desarrollo mexicano siga por un camino de servidumbre y servicio a la economía de Estados Unidos. ¿Puede México trazar su propio camino independiente, mientras aprende del gran éxito de la República Popular China?

Justin Worland, Mexico Charts a New Path on Climate Change, Says Environment Secretary Time. Alicia Bárcena, the country’s new environment secretary, spelled out an aggressive climate agenda for the country: dramatic expansion of renewable electricity generation, decarbonization of state-owned energy firms, and investments in a range of nature-based solutions.

Jared Laureles y Jessica Xantomila, Reforma laboral para repartidores conservará jornadas flexibles y dará seguridad social: STPS La Jornada. Serían 2.5 millones los trabajadores que se emplean a través de una plataforma digital, y no 658 mil como señala el gobierno federal.

Diana Baptista, Mexico pushes for “historic” labour rights for gig workers Context. Unions hailed the reforms as a big win for more than 600,000 underpaid, under-protected workers, saying the announcement could have a domino effect across the region.

Programa mexicano de Salud Casa por Casa contará con cerca de 22.500 especialistas Telesur. El Gobierno mexicano iniciará el programa Salud Casa por Casa en febrero de 2025, que contará con alrededor de 22.500 médicos y enfermeras como parte de la iniciativa.

Rossana Cambron, Is a peaceful transfer of power achievable through the ballot box? People’s World. What lessons does the duopoly-busting experience of AMLO and Morena have for the exceptional United States of America?

Angeles Cruz Martínez, Mineros protestan frente a embajada de Canadá por violaciones de Camino Rojo La Jornada. Trabajadores del sindicato minero realizaron una protesta frente a la embajada de Canadá en México para denunciar las violaciones que comete la Minera Camino Rojo, SA de CV, ubicada en San Tiburcio, Municipio Mazapil, Zacatecas en contra de los derechos y la libertad sindical, pues los presiona para que desconozcan a los dirigentes de la sección 335 del gremio.

Carolina Milan, For Mexico’s Sheinbaum, the race is on to harness nearshoring Bloomberg. Some dubious analysis in this business press piece regarding Mexico’s economy - reinvestment indicates significant investor confidence in Mexico.

Carlos Fernandez-Vega, Los dos barones de la televisión mexicana están en graves problemas La Jornada. Acumulan décadas de excesos, chantajes, evasión fiscal, operaciones turbias e impunidad garantizada al servir de parapeto y ariete del régimen prianista a cambio de enormes favores que no sólo se tradujeron en multimillonarias utilidades, sino en jugosos negocios paralelos gracias a su descarado amasiato con el poder político, del que recibían carretadas de dinero por medio de la pauta gubernamental. |

|

|

|

|

The Mexico Solidarity Project brings together activists from various socialist and left organizations and individuals committed to worker and global justice. We see the 2018 election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as president of Mexico as a watershed moment. AMLO and his progressive Morena party aim to end generations of corruption, impoverishment, and subservience to US interests. Our Project supports not just Morena, but all Mexicans struggling for basic rights, and opposes US efforts to undermine organizing and Mexico’s national sovereignty.

Editorial committee: Meizhu Lui, Bruce Hobson, Agatha Hinman, Victoria Hamlin, Pedro Gellert, Courtney Childs. To give feedback or get involved yourself, please email us! |

|

Subscribe! Get the Mexico Solidarity Bulletin in your email box every week. |

|

Web page and application support for the Mexico Solidarity Project from NOVA Web Development, a democratically run, worker-owned and operated cooperative focused on developing free software tools for progressive organizations. |