|

|

The weekly newsletter of the Mexico Solidarity Project |

|

Every issue archived online at mexicosolidarityproject.org/archives/ |

|

August 27, 2025 |

|

|

|

When Work Becomes a Crime |

|

Meizhu Lui, for the editorial team |

|

|

Under current US policy, an estimated third of workers from other countries working in the US are deemed “criminals” and therefore subject to arrest, indeterminate detention and deportation. How did we get to this point?

The US was founded by European nationals who migrated voluntarily. They settled in North America, killing or forcibly driving off the Indigenous populations to get what they needed — land. To work that land, they turned to Africa and shipped back people in chains, designating them legally as “chattel,” not humans. Later, on the west coast, sea captains turned to China for cheap, unfree and expendable labor. The Chinese were “shanghai’d,” or kidnapped — men as unwilling sailors and women as prostitutes.

Besides enslavement and forced labor, labor shortages have often been remedied by bringing in temporary workers from other countries. That’s the idea favored by both Democrats and Republicans. They assure us that temporary contracted workers are the only “good” migrants and that expansion of the temporary guest worker program is the only way to bring in the foreign workers US businesses need.

To become a contract worker, some recruiters in Mexico hired by US growers ask applicants to show their hands. If rough and calloused, it means they make a good candidate. Recruiters act like modern day slavers, who examined the bodies of Africans, concerned with nothing more than their physical capacity to do back breaking work.

So who does that leave as “illegal”? Only the people who come voluntarily, as the original settlers did — but who don’t have their main criteria for legality: whiteness.

Today, Trump’s fat magic marker draws a harsh line between those with papers and those without. Working without a permit has become a serious crime, with horrific punishments such as being disappeared into El Salvador’s concentration camps.

As we search for better immigration policies, Maria Quintana’s research should make us all shift our focus. The frame of “legalization” doesn’t deal with the reality of the US’s need for more workers or with the lack of workers’ rights for both undocumented and temporary workers. How about using a human rights frame, honoring the humanity of all workers, whether US or foreign-born, temporary or permanent? |

|

|

The detaining and deporting of immigrant workers from Mexico and Central America has raised alarm in all of us. We are republishing our May 31, 2023 interview with Dr. Maria Quintana, who discusses how making migration a question of legality evolved and how it has put all migrant workers at risk. (Editors) |

|

‘Legalization’ Frame Hurts Migrant Workers |

|

Maria L. Quintana, an Assistant Professor in Sacramento State University’s history department, teaches courses that cover topics ranging from race, empire, and civil rights to labor, immigration, and Latinx history. Her book, Contracting Freedom: Race, Empire, and U.S. Guestworker Programs, was published in 2022. |

|

|

Do you have a personal connection to the story of “guest workers” in the United States?

My great uncle worked as a bracero, and I grew up in a neighborhood called la colonia, a former orange orchard that hired braceros. My family’s and my people’s history as the working backbone of California interested me, and I wanted to find out more about the colonial roots of the Bracero Program.

How did the idea of temporary work — based on a labor contract between an individual worker and employer — take hold in the US?

This idea originated in England. With slavery about to be ended in the early 1800s, slave owners in the British West Indies wondered who was going to be doing the work once they had no slaves. How could they get docile workers that they could control? |

|

Their answer — a system that described workers as “free” with contractual rights and paychecks — offered a solution that skirted the arguments against slavery. Plantation owners started to import workers from India to the British West Indies on this basis. |

|

Indian indentured laborers in the British EmpirePhoto courtesy of Paul Gregoire: Sydney Criminal Lawyers, 2020 |

|

In the United States, with the mass importation of Chinese after slavery’s abolition, some protested that “coolie labor” amounted to “slave labor.” This sentiment led to the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Acts, as well as the 1885 Foran Act, legislation that prohibited imported foreign labor.

But the Foran Act had a loophole that allowed Mexican workers with temporary contracts into the United States, and employers used this loophole in 1917, before US entry into World War I. But the program proved short-lived. The Mexican government ended it in 1921, in part due to the exploitation of workers that the loophole made possible.

|

|

By 1942, a new consensus had emerged, shared by conservatives and liberals. They agreed that importing foreign workers who could freely enter into legal contracts determining the terms of their employment would bring mutual benefits to both worker and employer.

Unions as well as employers supported this idea of contract labor. Legendary farm worker organizer Ernesto Galarza, for instance, felt that a labor arrangement modeled on Depression-era resettlement programs — efforts that provided internal US Dust Bowl migrants with housing and new skills — could benefit Mexicans as well. |

|

|

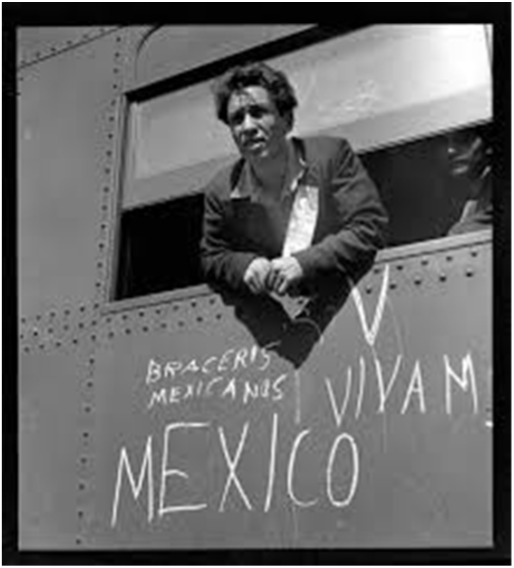

Photo: Dorothea Lange, 1942 |

|

These workers could learn new skills and take those skills back to México. So the Bracero Program originally faced little opposition.

The Bracero Program emphasized a worker’s freedom to accept a contract. Why do you say that guest worker programs actually served to legitimize US imperialism?

Contracts for temporary labor coerce. They tie a worker to a single employer, with no supervision of the contract to guarantee a basic standard of living.

Labor contracts also expand state power over immigrant workers. In effect, the “legality” of these contracts produces the problem of “illegality.” You cannot be “illegal” without a “legal status” for comparison. The US Border Patrol in 1924 began as a program too small to have any effect. But after 1942 — and the start of the Bracero Program — the Border Patrol’s numbers increased twenty-fold! |

|

|

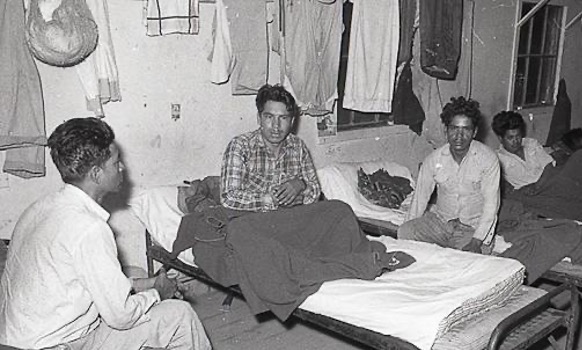

Photo: Braceros: Paul Richards, Estuary Press, 2013 |

|

Also in 1942, after Pearl Harbor, the government put the Japanese in the US, many of them agricultural workers, into concentration camps. Officials essentially co-constituted Japanese internment and the Bracero programs after multiple hearings that considered both populations and how to treat them. Living conditions for both were similar. |

|

An “empire” has complete state control over its population. In the United States, workers categorized as “foreign” became subject to US imperial rule. Workers did resist, with work stoppages and ripping up and breaking contracts by leaving their contractual employer. But their moves to escape their contracts broke the law. “Legality” increased oppression.

Did the growing civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s impact the braceros? |

|

|

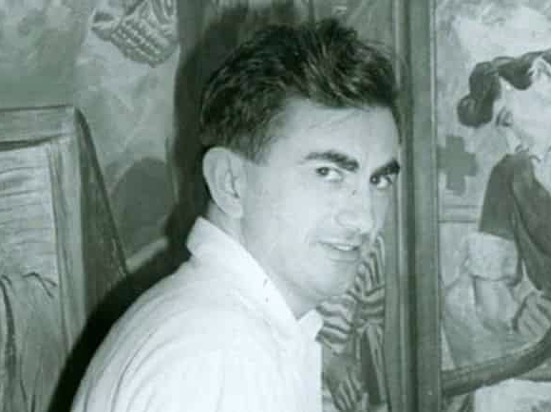

Ernesto Galarza: AFL-CIO, National Hispanic Heritage Month Profiles, Kenneth Quinnell |

|

Ernesto Galarza, appalled at the actuality of the Bracero Program, spent the rest of his life fighting bracero mistreatment. The National Farm Labor Union — the NFLU — that Galarza led tried to organize braceros with domestic farmworkers, but the growers could just fire “troublemakers” and replace them with either contract or undocumented workers.

Immigrant workers came to be seen as a problem, a group that undercut efforts to organize and protect domestic/citizen workers. |

|

Even among union organizers, the division became not just a conflict between workers and bosses, but also between domestic and migrant labor. The question in my research became, “Civil rights for whom?” The struggle for civil rights left out guest workers.

How and why did the bracero program end, and what has happened since then?

The United Farmworkers finally brought national attention to the reality of the conditions braceros labored under, and the 1960 network television documentary Harvest of Shame reached a wide audience. The Bracero Program ended in 1964, with, once again, the debate around that move stressing the need to protect domestic workers.

In 1986, to deal with the problem of predominantly Mexican undocumented workers, the Immigration Reform and Control Act — the IRCA — became law. This legislation traded off granting some immigrants a path to citizenship with making other immigrants even more vulnerable to deportation. |

|

Since then, with the continued liberal consensus on the issue as “legalization,” that trade-off has been part of every major immigration reform proposal.

The new H2-A rules on the “Temporary Agricultural Employment of Foreign Workers” allow more workers to come into the US with individual contracts that tie them irrevocably to individual growers and make them vulnerable to corrupt recruiters in México.

These rules subject agricultural laborers without papers to the growing militarization of immigration control. We’ll see deportations — already at all-time highs — increase even more, since legalization requires an expansion of state power to enforce the law. Contract labor remains bad for both new guest workers and undocumented laborers already working. |

|

|

Contracting Freedom, Maria L. Quintana, 2022 |

|

What can we do?

We must defend all farmworkers. Our agricultural industry depends on them. We must demand the same borderless world that corporations and capital live in. We must demand that worker rights be the same for all workers, citizens and migrants alike.

For those of us who oppose colonialism and imperialism, we must recognize that contract labor perpetuates those systems of oppression. |

|

|

|

|

In a New Wrapper: Mexico's Own Chocolate |

|

This article was written and published by Chocolate Affairs Magazine. We have edited it for length and clarity.

Combining economic justice with cultural pride, Mexico has officially launched Chocolate Bienestar, a new, all-natural chocolate bar sold in government-run Bienestar stores. Made with 35% cacao, the bar is both affordable and ethically sourced.

Its launch is part of the Mexican government’s broader campaign to use its state-operated retail network for distributing essential foods and locally produced goods at accessible prices. Similar to other Bienestar offerings like rice, milk, or beans, this chocolate bar serves dual purposes: nourishing families and strengthening regional economies. The chocolate is made from cacao cultivated in Tabasco and Campeche, two of Mexico’s historical cacao-growing states, which have long produced premium cacao. But, in recent years, many of these smallholder farmers have struggled due to erratic weather patterns, unstable prices and limited access to international markets.

The Chocolate Bienestar program guarantees participating farmers fair prices and a stable demand pipeline. Government officials say cacao is sourced through ethical procurement partnerships that prioritize small-scale, often Indigenous producers. The initiative not only offers a dignified wage but also creates long-term pathways for rural development and climate resilience.

With the chocolate processed and packaged by Liconsa, a government-backed food company, the entire supply chain remains under public oversight—further ensuring transparency, food safety and accountability.

But Chocolate Bienestar is also loaded with cultural resonance. Farmers in Mexico have cultivated cacao for thousands of years, with cacao serving as currency and as a sacred offering in Mesoamerican civilizations like the Maya and Aztec. This humble bar is not just a product — it’s a revival of ancestral knowledge and a step toward reclaiming sovereignty over a native ingredient that is globally cherished.

Chocolate Bienestar fuses heritage, sustainability, and food justice into one glossy brown wrapper. For many consumers, especially those in marginalized communities, it offers a wholesome treat made with real cacao—without the cost or compromises of commercial brands. For farmers, it offers stability and dignity. For the country, it marks a modern reimagining of one of Mexico’s greatest gifts to the world. |

|

|

|

Recent news reports and commentaries, from progressive and mainstream media, |

|

Ken Klippenstein, Military Preparing Attacks on Mexican Cartels. The Trump administration has directed the military to prepare for lethal strikes against cartel targets inside Mexico.

Bernardo Bátiz V., Poder Judicial; una revolución La Jornada. Ese cambio histórico terminó finalmente con la aprobación de la reforma constitucional, quedan pendientes recursos en tribunales internacionales, que no podrán dar marcha atrás a la reforma ni tendrán más valor que una declaración; no pueden oponerse a la decisión soberana que aprobó los cambios con los requisitos exigidos por nuestra Constitución.

David Bacon, Indigenous Communities From Southern Mexico Refuse to Bow to ICE in California Truthout. Increasingly targeted in immigration raids, Mixteco and Triqui communities hold festivals of resistance.

Presidenta de México aclara: No tenemos ningún acuerdo con la DEA HispanTV. La presidenta de México, Claudia Sheinbaum, negó que su país estuviera trabajando con la DEA en un plan antidrogas, como lo había dicho la agencia estadounidense.

Oscar Lopez, ‘Historic’: how Mexico’s welfare policies helped 13.4 million people out of poverty The Guardian. Experts are enthusiastic about poverty reductions achieved under former Mexican president Andrés Manuel López Obrador.

Pablo Ferri, Todo pasa por Harfuch en México El País Mexico. La llegada de Omar Reyes a la UIF refuerza el catálogo de herramientas del zar de seguridad de Sheinbaum. Solo se le escapan las aduanas y el despliegue territorial de los militares.

Sheinbaum Announces Visits to Mexico by Macron and Carney Telesur English. The meetings will focus on security, trade, and investment amid U.S. tariff tensions.

Embajadora de Palestina urge a México a “hacer más” y a “hablar claramente y sin titubeos” Proceso. “La moralidad no es opcional, es obligación", sostuvo la diplomática durante una conferencia que ofreció ante una atiborrada Aula Magna de la Facultad de Filosofía y Letras de la UNAM.

Jon Michael Raasch, Trump sends shockwaves with secret plan to use unauthorized 'lethal strikes' against Mexican cartels The Daily Mail. 'The Department of Defense will not comment on future operations considering operational security,' a Defense Department spokesperson said in a statement.

CATEM, el sindicato de Pedro Haces, acumula acusaciones de extorsión en 6 estados Sin Embargo. En diversos estados del país surgen acusaciones contra la CATEM, sindicato de Pedro Haces, sobre delitos que van desde la extorsión al secuestro y la desaparición. |

|

|

|

|

The Mexico Solidarity Project brings together activists from various socialist and left organizations and individuals committed to worker and global justice. We see the 2018 election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as president of Mexico as a watershed moment. AMLO and his progressive Morena party aim to end generations of corruption, impoverishment, and subservience to US interests. Our Project supports not just Morena, but all Mexicans struggling for basic rights, and opposes US efforts to undermine organizing and Mexico’s national sovereignty.

Editorial committee: Meizhu Lui, Bruce Hobson, Agatha Hinman, Victoria Hamlin, Courtney Childs, Pedro Gellert. To give feedback or get involved yourself, please email us! |

|

Subscribe! Get the Mexico Solidarity Bulletin in your email box every week. |

|

Web page and application support for the Mexico Solidarity Project from NOVA Web Development, a democratically run, worker-owned and operated cooperative focused on developing free software tools for progressive organizations. |