|

|

|

|

The weekly newsletter of the México Solidarity Project |

|

|

|

Online at mexicosolidarityproject.org |

|

August 24, 2022/ This week's issue/ Meizhu Lui, for the editorial team |

|

|

Photo: Guelaguetza 2022, Daniel McCool |

|

When Your Government Happens to Be Your Boss |

|

When you work for a General Motors or an Amazon, you can expect the owners and execs to be out to make as much as they can — for themselves — by extracting as much out of you for as little as they can. Where to turn? Workers often try to get their government to protect them against predatory employer practices, by setting safety standards, for instance, or fighting to raise the legally mandated minimum wage.

But what if the government happens to be your boss? If you’re cleaning municipal offices and have to use hazardous chemicals or teaching school and have to buy classroom supplies with your own money, you can’t look for help from the very entity that oppresses you.

How can public sector workers overcome this squeeze? Public sector workers directly serve the people, and support from the people they serve can give them a power greater than any ruling party.

Teachers in the Mexican state of Oaxaca, as we learn in our interview this week with René Gonzalez, champion the families of poor rural students from communities like his indigenous Ayuuk/Mixe village. These teachers don’t walk alone when they walk out on strike. Their concerns reflect student concerns, their anger the anger of local people, their resistance the resistance of entire communities. |

|

|

|

Don’t miss an issue. Subscribe to the weekly México Solidarity Bulletin! |

|

|

|

|

Teachers in Rural Oaxaca: Fighters for Justice |

|

René Oswaldo González Pizarro teaches in the indigenous public education system of Oaxaca, Mexico. He was born in the mountains of Oaxaca as part of the Ayuuk nation, known in Spanish as the Mixe people. A graphic designer, González co-founded the Colectivo Zape, a group focused on social issues. His activism has had him working on everything from posters and murals to graffiti and digital art — to being a General Assembly delegate for Sección 22 of Oaxaca’s teachers’ union.

What made you want to be a teacher? |

|

|

It’s in my DNA! I’m Ayuuk and grew up in a poor mountain village in Oaxaca. Both my parents taught. Education in México, ever since the 1917 Constitution, has been free through middle school. The government provides for the school building — one room in our case — and utilities and teachers. But the government doesn’t pay for supplies.

I remember a kid in my class who had just a stub of a pencil with no eraser that he kept using until it just became too short to hold. My parents bought materials for their students out of their own salaries. I was amazed to find out later, when I went into the city and saw a private school, that they had toilet paper and soap! |

|

My parents took me to my first demonstration when I was still a kid in the 1980s. Living in the small villages, teachers knew the needs of their students, their neighbors. These teachers made social demands — free textbooks, free lunches, free pencils!

The teacher group you support, the CNTE, formed in opposition to the SNTE, the government’s favored teacher union. Why?

The SNTE, a “company” union, has historically been tied to the PRI, México’s long-time governing party. |

|

|

Photo: a Mixe village |

|

The CNTE came out of the radical movement of the 1970s, inspired in part by the 1968 student rebellion. CNTE’s biggest early victory — forcing the resignation of a SNTE president — came in the 1980s.

That victory proved short-lived: An equally undemocratic bureaucrat replaced the president and kept the position for decades! But the CNTE stayed within the SNTE and did not disband. It continues to push internally for union democracy, and people know it externally for its militancy in insisting on better benefits for teachers and their communities. |

|

CNTE’s Section 22 in Oaxaca, one of the group’s strongest sections, has become widely known for its militant actions. In a number of demonstrations over the years, teachers and their supporters have given their lives — but we don’t give up.

The famous/infamous CNTE-led strike of 2006 had a major impact. |

|

|

Photo: SubVersiones |

|

Yes. In 2004, a newly elected authoritarian governor in Oaxaca began ruling with a mano dura, a hard hand. At the time, I hadn’t yet become a teacher. I was working in a graphic arts collective.

Every year on May 1, Workers’ Day, teachers in Oaxaca hold a demonstration and bring a list of their demands before the government. On May 15, Teachers Day, they hold another demonstration and set up encampments — technically illegal — in the central square, the zócalo. They begin negotiations and wait for the contract to get settled.

In 2006, on June 14, the police attacked the annual teacher encampment with tear gas and bullets. My sister and brother, both teachers, got me and said, “Let’s go to the zócalo to protect the encampment!” The attack enraged local people. They flocked to the zócalo and took it back, and the struggle soon broadened from a teacher union action to a social movement. The federal police under Vicente Fox then moved in with massive force, killing 17 and injuring hundreds. By December, the government had broken the strike. |

|

Teachers would go on to work hard in 2006 for the progressive presidential candidate, Lopez-Obrador, but his defeat led to a sense of failure, and the teachers moved away from electoral work. The CNTE today still does not engage in electoral activity. They believe change comes from grassroots struggle by the rank-and-file.

Earlier this month, Oaxaca saw two indigenous Guelaguetza festivals, one official and one put on by the CNTE. How did CNTE become involved?

The many indigenous nations of Oaxaca — we have 16 different indigenous languages — have had since before Columbus a tradition of gathering together, picking flowers, and performing rituals. |

|

|

Photo: Guelaguetza 2022, Daniel McCool |

|

In 1932, the government decided to make this tradition an official event and turned it into a showcase of different dances and costumes. The indigenous festivals have become more and more a money-making tourist attraction, with tickets sold on the internet. They’ve became unaffordable to native Oaxacans.

After the 2006 attack, the still defiant CNTE activists decided to take back the Guelaguetza by doing one themselves, “for the people.” They see the protection of culture as necessary for a relevant and meaningful education. |

|

The alternative Guelaguetza Popular resists the government’s appropriation of indigenous culture, and graphic art blooms on the streets of Oaxaca, a vibrant center for the arts. One cheeky art poster this year even read “Death to bourgeois tourists”!

The demonstrations and strikes you’ve been part of have been local to Oaxaca. How much do you think international solidarity matters?

My eyes opened after 2006. I took photos of the tear gas canisters and the rubber bullets lying on the ground after the police attack. They were made in the USA. Later, I saw photos of the same items used against demonstrators in Ferguson, Missouri who were protesting the murder of a young black man. And then I saw photos of the same items used against Palestinian demonstrators. |

|

|

We’re struggling against the same forces. I’ve been able to talk with teachers on strike in Chicago and New York. Wow, I thought to myself, teachers striking in the US! That doesn’t happen in the movies! With solidarity, we can all keep struggling. |

|

|

No Joke: The New Cheech Marin Chicano Art Museum |

|

“Together, we hope to bring every aspect of Chicano art to this region as well Cheech Marin |

|

The Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art & Culture of the Riverside Art Museum just opened this past June in California. This is a big deal! The well-respected and beloved Marin, half of the comedy duo Cheech and Chong, has been a long-time collector of Chicano art. Now he’s parlayed his fame and fortune into a gift to his community. |

|

|

The new center’s vibrant, sassy, and innovative online intro video — so unlike anything from the cool intellectual traditional big power art institutions — says it all. This museum preserves treasures and makes them accessible. Among the many iconic artists with works on display: Patssi Valdez, Sandy Rodriguez, Carlos Amaraz, Frank Romero, Judithe Hernández, and Gilbert “Magú” Liján. |

|

|

I feel a personal connection to the works of Patssi Valdez. This fine artist from East L.A. uses identifiable images and abstraction to make dazzling portraits of the evidence of lives being lived.

Patssi Kitchen (2000) |

|

The technically brilliant painting of Sandy Rodriguez comes across as gorgeous, intense — and very political. Wake up, everybody!

Tear Gas No. 1 Ferguson (2014)

|

|

|

|

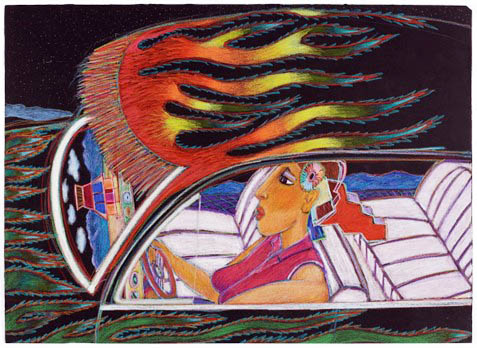

Magú Lujan, all-the-way modern in his comic book-influenced storytelling, makes me think of José Guadalupe Posada, a 19th-century Mexican lithographer. Go figure!

La Ella Cruising (2004) |

|

The Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art & Culture — definitely not your parents’ art museum — represents a new people and a community-based idea of who art should be for. You go, Cheech! Light one up for me! |

|

Activist Vicky Hamlin is a retired tradeswoman, |

|

|

|

Recent news reports and commentaries, from progressive and mainstream media,

Oscar Lopez, México Arrests Top Prosecutor in Case of Missing Students and Issues 80 Warrants, New York Times. The country’s former attorney general, accused of covering up the probable massacre of 43 students, now faces charges of forced disappearance, torture, and obstruction of justice.

Áxel Chávez, Osorio Chong, Omar Fayad y otros políticos de Hidalgo ofrecen su apoyo a Jesús Murillo Karam, Proceso. Políticos hidalguenses, entre ellos el gobernador Omar Fayad, defendieron a Jesús Murillo Karam, detenido el viernes por el caso Ayotzinapa.

AMLO calls on LatAm leaders to urge halt to ‘interventionism’ by Canada, US, México News Daily. México’s northern neighbors should respect sovereignty of other nations in the region, the Mexican president says.

Mireya Cuéllar, AMLO: conocer la verdad fortalece a las instituciones, como el Ejército, La Jornada. El Presidente comentó algunos detalles de la reunión con los familiares de los estudiantes del caso Ayotzinapa, quienes escucharon que sus hijos fueron víctimas de “un crimen de Estado”.

In México Resort Town, Squatters Make a Stand Against Developers, Associated Press. Police in Tulum are trying to evict squatters so towering condos can be built next to wood and tarpaper shacks. Residents, tired of foreign investors excluding local people from their own coast are fighting back.

David Bacon, California Farmworkers March to Urge Newsom to Sign Voting Rights Bill. California’s labor law for farmworkers prohibits the use of intimidation. But decades of hearings amply document growers' use of fear to prevent unionization.

AMLO aumentará pensión de adultos mayores 25%; ¿cuánto depositarán ahora y en qué fecha? Indigo. AMLO también adelantó que para el año 2024 también habrá un aumento del 25 por ciento; esto con el objetivo de que al terminar su sexenio, la pensión esté al doble de cómo inició en su administración.

Labor Rights and the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement, U.S. Bureau of International Labor Affairs. Useful reference: The agreement prioritizes labor obligations by including them in the core of the agreement and making them fully enforceable, a major change from NAFTA.

¿Quiénes van a ser los candidatos a la presidencia en 2024?: Resultados del tracking diario hoy 20 de agosto de 2022, sdpnoticias. Los resultados del tracking diario de los posibles candidatos a la presidencia para las elecciones 2024. |

|

|

The Mexico Solidarity Project brings together activists from various socialist and left organizations and individuals committed to worker and global justice who see the 2018 election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as president of México as a watershed moment. AMLO and his progressive Morena party aim to end generations of corruption, impoverishment, and subservience to US interests. Our Project supports not just Morena, but all Mexicans struggling for basic rights, and opposes US efforts to undermine organizing and México’s national sovereignty.

Editorial committee: Meizhu Lui, Bruce Hobson, Bill Gallegos, Sam Pizzigati, Courtney Childs, Victoria Hamlin, Agatha Hinman, Steven Hollis. To give feedback or get involved yourself, please email us! |

|

|

|

Web page and application support for the México Solidarity Project from NOVA Web Development, a democratically run, worker-owned and operated cooperative focused on developing free software tools for progressive organizations. |