|

|

|

|

The weekly newsletter of the México Solidarity Project |

|

|

|

Online at mexicosolidarityproject.org |

|

September 21, 2022/ This week's issue/ Meizhu Lui, for the editorial team |

|

|

Hyoung Chang/MediaNews Group/Denver Post |

|

Prison to Detention: Frying Pan to Fire |

|

Many of us, for reasons ranging from demonstrating and drugs to DUIs, have found ourselves arrested and incarcerated, usually when we’re young. Count two of our interviewees this week, Pedro and Gustavo, as part of this crowd.

Most of us, after finishing off our allotted time, can leave prison behind and go back to our loved ones. But for those too young to know they were crossing any legal boundaries when their parents carried them into the US, it’s out of the frying pan and into the fire.

The US Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency, better known as ICE, usually only imposes detention on people considered a threat to public safety or a flight risk. Pedro and Gustavo had proven to be neither. Both had participated in the California state prison system’s firefighter program. That system’s officials had given Pedro and Gustavo chainsaws and sent them out to work in public. You don’t let public menaces do that!

And yet none of that positive firefighting behavior mattered to ICE. The agency transferred Pedro and Gustavo straight from prison into ICE detention centers.

Hospitals treating an undocumented patient do not have to discharge that person into a detention center. Schools do not interface with ICE. And yet prisons do. Why? Ending a prison sentence should be a moment of hope and renewal. Do we want our society to encourage redemption — or despair? |

|

|

|

Don’t miss an issue. Subscribe to the weekly México Solidarity Bulletin! |

|

|

|

|

ICE Detainees: ‘Our Voices Need To Be Heard!’ |

|

Esperanza Cuautle Velazquez co-directs Pangea Servicios Legales, an agency that provides guidance and legal services to people facing deportation proceedings. She works directly with people in ICE detention facilities, and two of those detainees, Pedro and Gustavo, are now participating in a detention facility labor strike. We recently spoke to the three about the ICE detainee situation that people like Pedro and Gustavo — we’re using only their first names here — are facing.

Pedro and Gustavo, how did you land in an ICE detention center? |

|

|

Pedro: My parents brought me from México 34 years ago when I was about four months old. In the 1990s, we tried to apply for citizenship, but didn’t succeed. As a teenager, I hadn’t grown up with the necessary tools to overcome the social issues I encountered, so this put me into a broken justice system that eventually sent me to prison.

While there, I had a record of good behavior and proved I was not a threat to public safety or a flight risk, and that earned me a place in “fire camp,” a state prison system program. I worked two seasons as a firefighter during California’s biggest wildfires in 2020 and 2021. But instead of being released after my prison sentence ended — like other prisoners who finished their sentences — prison officials immediately transferred me to a federal ICE detention center in McFarland.

Gustavo: I have a similar story, except my parents came from El Salvador. After landing in prison, I took initiative to redeem my mistakes. I took college courses and was accepted into fire camp. From 2019 into 2022, I worked as a first responder fighting fires throughout California. People saw us save their homes and shook our hands in gratitude.

I completed my sentence, but then, instead of sending me home, the prison transferred me to the Golden State Annex detention center. I had paid my dues. But the prison handed me off to ICE for indefinite detention, despite my positive record. |

|

What’s been the hardest part of your detention?

Pedro: The uncertainty. In prison, you have a release date to look forward to. Here, who knows how long you’ve got? The ones affected most? My four kids. They expected me home for the holidays when my prison term ended. My detention devastated them.

You also don’t know what you’re going to miss in detention. During my prison time, I lost my best friend — my father — and I couldn’t even grieve properly. This crushes the spirit, the heart, the mind.

Gustavo: Uncertainly about the future has been the hardest part for me. I’m scared I’ll be deported to El Salvador, a country I don’t know. I’m afraid of getting tagged as a gang member. I could get killed. I thought I was putting the incarceration chapter of my life behind me. Now I’m living in even greater jeopardy. I worked really hard to become a better version of myself. I wanted to put all the knowledge and skills I acquired into practice. Now I’m still confined for the sole reason of not having legal status. |

|

|

Gustavo: At the fire camp |

|

“Detention” sounds better than “incarcerated,” and “detention center” sounds better than “prison.” How do the detention centers and prisons compare?

Pedro: A profit-hungry private company, the GEO Group, has a contract with ICE to run detention centers. In both prisons and detention centers, we shop at the commissary for necessary items like deodorant. ICE uses the same commissary vendor as the state prisons do, but ICE detention center costs run 50 to 100 percent higher. A 15-minute phone call in a publicly run prison costs 35 cents. That same call costs $1.05 in a GEO facility. |

|

Gustavo: Both prisons and detention centers profit off of human beings, creating a vestige of slavery. Both places exploit our labor. We got paid $1 an hour in fire camp. We get paid only $1 per day for the janitorial work they force us to do here, less than 1 percent of the California minimum wage. Compare that to George Zoley, the CEO of the GEO Group. He took home $11,836,480 in 2021! |

|

|

Photo: Joyce Xi and the Dignity Not Detention coalition |

|

How did your strike get started?

Gustavo: This past April 26, after ongoing problems with delays in medical care and other deplorable conditions at the Mesa Verde detention facility, folks housed in Charlie dorm had enough. They decided to withhold their labor. As of September 17, detained people at Mesa Verde have been on strike for 144 days.

Our demands: that we be paid according to the California minimum wage of $15 per hour, that we be treated with dignity and respect by the facility administration, that ICE and GEO improve the substandard conditions we face. As of today, ICE and the GEO have not budged. Instead, they’ve retaliated against strike organizers. They’ve sent them to solitary confinement and threatened to transfer them out of state.

Esperanza, advocates and attorneys filed a lawsuit contesting the $1 a day pay. Do you see that pay as the main abuse or the issue that has the best chance of a legal victory that would draw attention to conditions in these facilities?

Esperanza Cuautle: This isn’t either the first strike or the first time that people in detention have protested their conditions. In fact, multiple complaints to Homeland Security’s Office of Civil Rights and Civil Liberties have called out ICE over issues ranging from the absence of balanced meals and contaminated water to the lack of training in handling toxic chemicals and medical negligence. The Mesa Verde and Global State Annex detention facilities have only one doctor for both facilities and not anyone to handle mental health needs!

A Washington state suit against another GEO Group facility did challenge the $1 a day pay. A jury found the detainees to be employees who should have been paid the minimum wage — and found that they deserved back pay as well. That verdict encouraged us to file a suit too, and if we win, that victory will hit the GEO execs where they most don’t want to be hurt: in their pocketbooks. But GEO is appealing the Washington state case, and resolving our own suit will likely take several years. |

|

Undocumented people like you, Gustavo and Pedro, pose no threat. What can we do to abolish ICE’s detention center system?

Gustavo: We could close these places down. Our lives matter. Throughout decades of history, immigrants of color have been targeted and excluded, detained and deported. This must stop. |

|

|

Photo: LCIP |

|

Abolishing the detention system will be a long-term fight and require the organizing and mobilizing of everyone in our communities. Those of us in ICE custody are going to continue to challenge the derogatory and criminalizing narrative about us. We’re going to publicly share our stories of struggle and resilience. We’re going to urge members of Congress to hold ICE accountable for its corrupt and inhumane practices. Our voices need to be heard!

Esperanza Cuautle: I want to emphasize the organizing and mobilizing that Pedro and Gustavo are talking about. Those of us on the outside need to call on our congressional representatives, on state agencies, on all our labor and community allies. We need them all to join the fight for justice, liberation, and family reunification.

And to help those strikers who now have no money for necessities at their detention center commissary, please donate to the strike fund! |

|

|

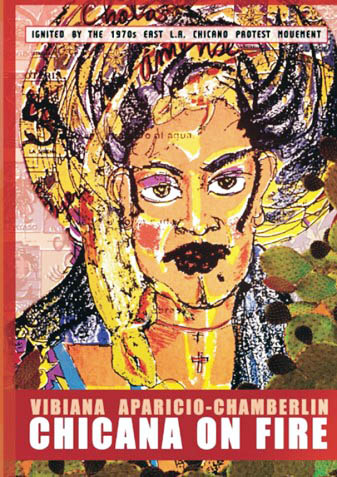

Chicana on Fire: A Review of a Vital New Collection |

|

Born and raised in East L.A., Vibiana Aparicio-Chamberlin has become a vibrant activist, writer, and visual and performing artist. Her new collection of poetry and stories, Chicana on Fire: Ignited by the 1970’s East L.A. Chicano Protest Movement, pays tribute to her Boyle Heights neighborhood. We’ve adopted this passage from a review of the book by Jimmy Centeno that has just appeared in Latino Rebels. |

|

Opening Aparicio-Chamberlin’s book evokes an aroma of wet earth. She braids history and politics into poems and stories, and her poetry and storytelling at times take volcanic dimensions, eruptive and explosive. In other instances, her poems reflect soft swells of maternal loving care dedicated to family and loved ones.

Aparicio-Chamberlin’s feminist consciousness, specifically Chicana, weaves family, community, and her Mexican heritage through her Indigenous roots and mythology. Her writing comes across as a cactus tree with arched arms full of prickled-pear fruit in resistance against droughts of love and the intolerable heat of racism. |

|

|

The 1970 police assault on a Chicano peace protest against the Vietnam War at Laguna Park in East Los Angeles sparked Aparicio-Chamberlin’s poetry of protest. In Attacked, Tear Gassed, and Bludgeoned by Sheriffs at the National Chicano Moratorium Against the War in Vietnam, East Los Angeles, August 29, 1970, Aparicio-Chamberlin writes: “I froze; lost my speech. I cried inside my head.” Her invisible tears, fossilized in this poem like amber.

In Don’t Open the Door, Aparicio-Chamberlin brings us close to the frightful drama of an undocumented family. The poem starts as a letter from a teacher to the mother of Alejandro, warning her to tell her son not to open the door, to be quiet and stay still if he hears a knock. The mother’s consecutive instructions of “don’t do this” and “don’t do that” string together like beads on a rosary. Aparacio-Chamberlin is rescuing and preserving memory that allows her community the space to become the authors of their own history.

Palestine, Haiti, Vietnam — all of the Global South — appear in her political poetry. In Oh, Palestine, Aparicio-Chamberlin yearns to build a perfumed bridge to be close to her Palestinian sisters in struggle. In her poem dedicated to Haiti, she describes her desire for a small plot of land for the poor: “No more quaking only the Earth stretching and scratching to loosen the soil for beans and corn to grow for you.”

Chicana On Fire blazes with the ganas — desire — to build a different, more promising world for us all.

Jimmy Centeno has studied liberal arts at East L.A. Community College and Latin American studies at Cal State Los Angeles. He’s currently concluding a second master’s in art history. |

|

|

Recent news reports and commentaries, from progressive and mainstream media,

Kurt Hackbarth, México’s New Truth Commission Will Shine a Light on the Crimes of Its ‘Dirty War,’ Jacobin. Over a seven-year period in the 1970s successive Mexican governments disappeared, tortured, and killed dissidents from a wide variety of backgrounds. Now AMLO has launched the first truth commission to address the government’s crimes.

Isabel González Aguirre, Detienen a general de batallón en Iguala por caso Ayotzinapa, Excelsior. De las cuatro órdenes de aprehensión contra miembros del Ejército ya se cumplimentaron 3, informó el subsecretario de Seguridad.

Alberto Fajardo, Roberto Ramirez, and Josue Gonzalez, México City Faces US Remote Worker Surge Amidst Large Wealth Gap, Reuters. A wave of international visitors, untethered from daily office commutes by Covid, is pricing out local residents.

Gustavo Castillo, Emir Olivares y Alonso Urrutia, Fuerzas armadas refrendan sujeción total al poder civil, La Jornada. El secretario de la Defensa Nacional, el general Luis Cresencio Sandoval, ha señalado que las fuerzas armadas están subordinadas al poder civil que encabeza el presidente López Obrador.

Daniel Stewart, López Obrador defends social programs as a formula for taming violence, MSN. López Obrador reports his government is allocating “more support to indigenous municipalities because justice is giving more to those who have less.”

INAH condena subasta en Francia de bienes arqueológicos mexicanos, La Jornada. La Secretaría de Cultura federal condenó la subasta anunciada por la casa francesa Maison de Vente Millon et Associétes en la que se incluyen 17 bienes arqueológicos que forman parte del patrimonio cultural del país.

Andrew Schneider, México’s president is unlikely to reopen the country’s energy sector to private investment, Houston Public Media. The dispute will likely end with US tariffs on Mexican exports. That could include Mexican oil, a move that would hurt Texas refineries.

México propondrá a la ONU plan para terminar guerra en Ucrania y tregua mundial de 5 años, anuncia AMLO en desfile, Animal Politico. En el desfile por el aniversario del inicio de la guerra de independencia, el presidente anunció que Marcelo Ebrard llevará el planteamiento a la Asamblea General de la ONU.

Maria Eloisa Capurro, Matthew Bristow and Maya Averbuch, Inflation Is Wiping Out Latin America’s Middle Class, Bloomberg. From Mexico to Brazil, high inflation is widening the gap between rich and poor in what already rates as the world’s most unequal region.

Annarella Grimal, AMLO promete más médicos cubanos en México y salud gratuita para 2023, CiberCuba. Sobre los galenos cubanos, destacó su presencia en el país e insistió en que traería a otros, aunque molestara a los oponentes políticos. |

|

|

The Mexico Solidarity Project brings together activists from various socialist and left organizations and individuals committed to worker and global justice who see the 2018 election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as president of México as a watershed moment. AMLO and his progressive Morena party aim to end generations of corruption, impoverishment, and subservience to US interests. Our Project supports not just Morena, but all Mexicans struggling for basic rights, and opposes US efforts to undermine organizing and México’s national sovereignty.

Editorial committee: Meizhu Lui, Bruce Hobson, Bill Gallegos, Sam Pizzigati, Courtney Childs, Victoria Hamlin, Agatha Hinman, Steven Hollis. To give feedback or get involved yourself, please email us! |

|

|

|

Web page and application support for the México Solidarity Project from NOVA Web Development, a democratically run, worker-owned and operated cooperative focused on developing free software tools for progressive organizations. |