|

|

|

|

The weekly newsletter of the Mexico Solidarity Project |

|

Every issue archived online at mexicosolidarityproject.org |

|

|

|

April 10, 2024/ Meizhu Lui, for the editorial team |

|

|

|

Women in Politics: Rosario Ibarra |

|

|

Boys and girls are socialized differently. Boys are taught to aim for the top of a pecking order, to win. Girls are taught to nurture; they are responsible for the well-being of the whole family. So, what do boys want to be when they grow up? They might well say, “President.” Girls? “Me and my friends are going to…”

Women often enter politics after personally experiencing a collective need. Look at Malala Yousafzai, who won the Nobel Prize at age 17 and influenced a generation of girls. She never intended to be a public figure; she just loved learning, which the Taliban denied her when they banned girls from going to school. “Me and other girls have a right to education!”

As Heather Dashner Monk tells us, so it was with Rosario Ibarra de Piedra. In 1982, she ran for president of Mexico, the first woman to ever do so. Her trajectory began simply as a mother searching for a lost child. She bonded with other mothers, and collectively they started a political movement against government impunity and political repression. From there, her many friends encouraged her to find a bigger platform — the biggest platform! Running for president would not have crossed her mind if someone had asked her as a child, “What do you want to do when you grow up?”

The mothers began with pleas, their pleas morphed into demands; soft women's voices morphed into loud ones — amplified by the thousands of voices of their friends.

As we look at the women running for president of Mexico today, let’s not forget Rosario Ibarra and her clarion call for justice. |

|

For a deeper dive into current news and analysis in English, check out our media website. And definitely see the new English podcast ¡Soberanía! (Sovereignty) with José Luis Granados Ceja and Kurt Hackbarth. They entertain, while dismantling the lies and distortions about Mexico fed to us by the mainstream media. |

|

Don’t miss an issue! Sign up for a free Mexico Solidarity Bulletin subscription. |

|

|

A Woman for President: 42 Years Ago |

|

Co-founder of third wave feminism in Mexico, Heather Dashner disagreed with male socialist leaders who believed that women's liberation should wait until after the working class took power. Since the 1970s, she’s been at the forefront of every struggle for women's equality in Mexico. Dashner has edited two books where she and her fellow women comrades tell their stories, Feministas Trotskistas, and Rebeldes y Transgresoras: Feministas Trotskistas, Testimonios 1974-1992. |

|

|

Was Rosario Ibarra de Piedra a feminist? How did she become a political leader?

Rosario was not a feminist. She was a well-educated middle-class housewife who had studied medicine, married a doctor, and had four children. Her husband sympathized with the Communist Party, and their politics were left, but they were not activists.

In the early 1970s, her son Jesús Piedra went off to medical school. But instead of finishing, he dropped out of the family’s view. At that time in Latin America, an urban guerrilla movement had arisen — think Che Guevara. In Mexico, after the brutal repression of the student uprising in 1968 and the hunting down of political dissidents, many young people concluded that legal avenues to political reform were closed and armed insurrection was the only option. Jesús joined a revolutionary group, the September 23rd Communist League. |

|

In one last letter to his family (signed with his pet name, Wu-Lee, because his family thought he looked Chinese!), he wrote that he was okay, but he might never see them again, and he hoped they would understand. In 1973, he was involved in a major crime: the kidnapping and killing of a major industrialist in the large commercial center of Monterrey. In 1975, Jesús was caught; he then disappeared. |

|

|

Rosario Ibarra: Photo Sergio Dorantes/Sygma via Getty Images |

|

Rosario started looking for him. And never stopped.

How did she move from a personal search for her missing son to leading a movement of the families of the disappeared?

As she went from one government office to another, she met other mothers also searching for husbands or sons and realized that disappearances were a frigging plague!

Remember — this occurred in the middle of the “Dirty War,” which lasted from the 1960s to the 1980s. The Mexican government was supporting the US Cold War against communism. In the process, they broke up protests, jailed, tortured, exiled, murdered, and disappeared people. It’s estimated that at least 1200 people were disappeared, and most still have not been found, dead or alive. |

|

|

Ibarra speaks at a EUREKA demonstration |

|

Because Rosario had the social and economic chits to do so, she formed a committee, mostly of mothers, called the Committee in Defense of the Disappeared and Political Fugitives and Exiles, known by its acronym EUREKA. They wanted political prisoners freed from jail, the return of those exiled, and they defended those on the “wanted” list. The committee was reasonable; they demanded, “Show us the disappeared; if they are accused of crimes, bring charges against them, but do it publicly!”

Their work exposed to the entire nation the government’s role in politically motivated disappearances. As a result, they won amnesty for over 1,000 people, and freedom for 150 political prisoners. Some PRI leaders realized that their way of ruling was undermining the party's ability to stay in power; they announced a new rule that permitted parties, if they fulfilled a series of requirements, to be registered as legal with a right to run candidates. This opened up space for the left; the Communist Party, for one, became legal in 1979.

Rosario then ran for president in 1982 and 1988. What was her campaign like?

Because of her leadership in EUREKA, she was introduced to our Trotskyist party, the Workers' Revolutionary Party (Partido Revolucionario de los Trabajadores, or PRT), which had grown out of the 1968 student movement. Rosario was neither a feminist, a veteran of the 1968 movement, nor a Trotskyist — but she became our candidate for president.

Her base? In the late 1970’s, several large mass fronts emerged: the dissident movement within the teachers union (the largest union in Latin America); a national peasant coalition; and the National Coordination of Urban Popular Movements (which had Maoist politics). The current Morena candidate for Mexico City mayor, Clara Brugada, comes out of this last movement. A Women’s Front was formed in 1978. A national coalition of all these forces — women, left parties, labor, and so on — formed a united front against repression. |

|

Rosario was thus connected to all these movements. She campaigned in every state and always went to the jails to talk with prisoners. She talked with local movement leaders and met with governors with a list of demands based on her discussions with activists. In the state of Colima, she presented Mexico’s first woman governor with more than 60 demands; the only demand met was the founding of Mexico’s first public women’s help center. Her passionate speeches were electrifying. It wasn’t just me who couldn’t hear her without being moved to tears. |

|

|

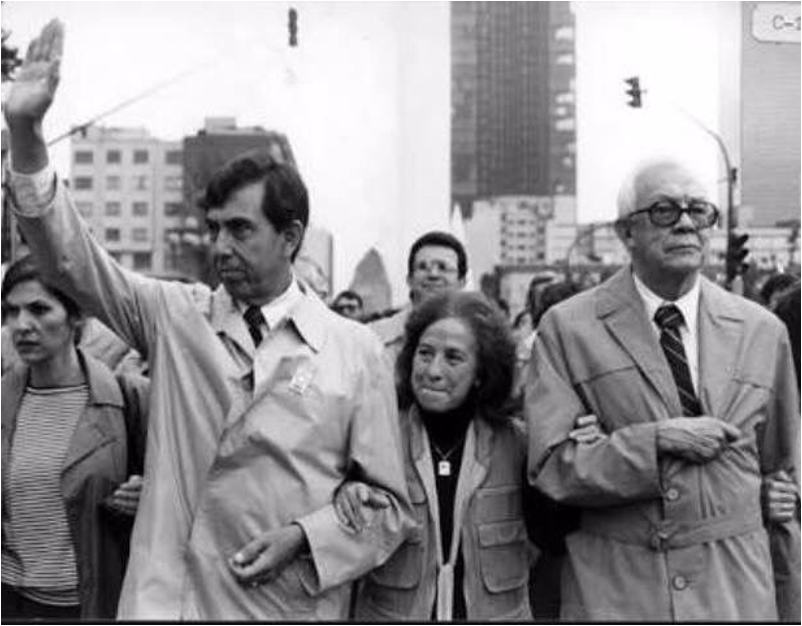

Campaigning with Heberto Castillo and Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, PRD presidential candidate in 1994: via Pinterest |

|

She lost the election but became a representative in Congress in 1985 and later a senator between 2006 and 2012. She was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize four times.

The anniversary of Rosario Ibarra’s death is on April 21. Did today’s movement for the disappeared grow out of her groundbreaking human rights work? How should we remember her?

No, the current movement isn’t a direct continuation of Rosario’s work. Since the “Dirty War,” disappearances continue, but not mainly for political reasons. Since 2006, they are mostly related to the war on drugs and collusion between government officials and cartels — but the issue of government impunity remains.

On October 23, 2019, in her last public act before her death, Rosario Ibarra was awarded the Belisario Domínguez Medal of Honor in Congress. At the end of her speech, read by her daughter, she handed the medal back to President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, saying, "Mr. President ... I don't want my fight to be unfinished ... I leave ... this precious honor in your custody, and

That was pure Rosario. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Campaign to Smear AMLO as a Narco |

|

|

A naturalized Mexican citizen, writer, playwright, and journalist Kurt Hackbarth is widely followed for his political commentary. He's regularly featured in Sentido Común, al Jazeera, Jacobin, and now co-hosts a weekly podcast, Soberanía, for the Mexico Solidarity Project's Media group. |

|

|

The current president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), will not be on the ballot in June, yet he remains a target for attacks. A dirty campaign, designed to cast doubt on the coming election’s legitimacy, attempts to link him and the party he founded, Morena, with the drug cartels. We’ve greatly condensed Kurt’s article; you’ve got to read the whole piece for the full flavor of his lively dissection of media attempts to cast AMLO as a narco-president. (Ed)

Accusation #1: Morena and organized crime will be allied in Mexico’s 2024 election.

On January 18, the Baker Institute for Public Policy at Rice University published its Mexico Country Outlook 2024. The “nonpartisan” institute is a hub of multinational energy interests financed by Chevron, ExxonMobil, Shell, British Petroleum, the Koch Foundation, the Mexican Business Council, and Kimberly-Clark de México (headed by opposition figure Claudio X. González Laporte).

The Institute did not disappoint its donors. The report included this juicy nugget: “Criminal organizations may even become an important electoral ally of MORENA in the June 2024 elections … Despite US pressure, the López Obrador administration simply will not confront organized crime … This is largely because the president’s party MORENA expects organized crime to operate in its favor during the 2024 elections.”

The report presents no evidence to support such extreme allegations.

Accusation #2: Organized crime financed AMLO’s 2006 campaign.

Less than two weeks later, on January 30, the media outlets ProPublica, InSight Crime, and Deutsche Welle published three pieces on the supposed relationship between organized crime and AMLO’s first presidential campaign in 2006. ProPublica attempted to show that drug traffickers had funneled $2 million to campaign operatives in return for promises that an AMLO administration “would facilitate the traffickers’ criminal operations.”

In Mexico the pieces faced blowback for simply rehashing a closed investigation from over a decade prior. (US prosecutors did not pursue the case because they were “underwhelmed” by the so-called evidence.)

Accusation #3: The cartels were involved in AMLO’s 2018 campaign as well.

On February 22, New York Times writer Alan Feuer and Mexico bureau chief Natalie Kitroeff offered up a feast of vagueness and insinuation: “American law enforcement officials” spent years looking into allegations (not facts) set out by “US records” and “three people familiar with the matter.” The piece never gets more specific: officials identified “potential links” and “possible ties” between cartels and AMLO’s associates but “did not find any direct connections” between the president and criminal organizations.

The Times admits that much of their information came from informants whose accounts can be difficult to corroborate and are sometimes incorrect. Given all this, the piece fails to rise above the level of chisme (gossip) and second- and third-hand chisme at that.

The Boomerang Effect.

The innuendo campaign was then viralized. Spanish social media analyst Julián Macías Tovar documented how a series of hashtags portraying AMLO as “narco-president” and presidential frontrunner Claudia Sheinbaum as ““narco-candidate” became multi-day trending topics on X/Twitter. But spelling errors in the hashtags allowed Macías Tovar to trace the origins of the trends to a series of troll centers in Spain, Colombia, and Argentina.

And something happened on the way to the land of character assassination: the script did not go according to plan.

In the two weeks following the New York Times article, Morena’s Sheinbaum gained five points in presidential preference polls, while Xóchitl Gálvez lost five. Even the right wing paper Reforma’s own polling found AMLO’s popularity had risen eleven points to 73 percent between January and March, the period of the stiffest attacks.

AMLO rebutted the allegations, framing them as attacks on national honor and sovereignty. “I represent a country, I represent a people that deserves respect … No one is going to come here — because we are not criminals, we have moral authority — and just because it’s the New York Times, sit us down in the dock of the accused. That was before when authorities in Mexico allowed themselves to be blackmailed. Not now.” |

|

|

|

|

Recent news reports and commentaries, from progressive and mainstream media, |

|

Fidel Gutiérrez, Heather Chen and David Shortell, ‘Outrage against international law’: Mexico breaks diplomatic ties with Ecuador over embassy raid CNN. U.S. backed regime in Ecuador raids Mexican embassy and assaults Mexican diplomat in order to illegally arrest the leftist vice president under Correa

Arturo Sánchez Jiménez, Agradece AMLO solidaridad tras asalto a embajada mexicana en Ecuador La Jornada. El presidente Andrés Manuel López Obrador agradeció este sábado la “solidaridad de mandatarios, dirigentes y organizaciones civiles de distintos países y del nuestro tras el asalto de la Embajada de México en Ecuador”.

Sheinbaum Envisions New Dawn for Mexico’s Anti-Corruption Battle Latin American Post. Claudia Sheinbaum’s anti-corruption plan represents a significant shift in Mexico’s approach to governance, with potential ramifications for the entire Latin American region. By advocating for institutional reform, digital transformation, and enhanced transparency, Sheinbaum positions herself as a catalyst for change, promising a future where governance is defined by efficiency, integrity, and accountability.

Kurt Hackbarth, Suicidio colectivo Sentido Común. Occidente, en palabras del analista Michael Brenner, "se ha separado de la realidad”. Basta echar un ojo a las reacciones a la propuesta migratoria de AMLO en las redes del programa "60 Minutes" para constatar eso.

Cody Copeland, Are migrants responsible for fentanyl in North Texas? Here’s what US border officials say Fort Worth Star Telegram. Nearly three-fourths of those caught attempting to smuggle fentanyl into the United States since October 2022 were U.S. citizens, and they brought in more than half of all fentanyl seized by U.S. authorities, the officials said.

Benjamín González Pérez, Faros, Pilares y Utopías La Jornada. Los tres programas comparten ideas fuerza similares y que, en 27 años de gobiernos de izquierda en la ciudad, representan la victoria de una visión que apostó por una transformación que incluyera, por muy lenta que sea, la incursión comunitaria y el empoderamiento ciudadano. Son espacios que otorgan servicios de la más diversa índole, revolucionando la visión de lo que se necesita para hacer frente a los problemas de la ciudad, y todos los servicios son gratuitos.

Thomas Graham, Candidate for mayor of Mexican city of Celaya killed on first day of campaign The Guardian. Bertha Gisela Gaytán was shot in a town just outside of the city of Celaya, where she was running for Morena, Mexico’s governing party.

Témoris Grecko, Forman influencers contra “populismos de izquierda” en América Latina Milenio. Al menos 16 asociaciones mexicanas, entre ellas, México Evalúa y el Centro Fox, forman parte de una estrategia de Atlas Network que promueve políticas liberales de derecha, según DeSmog.

Anna Gordon, How Mexico Became a Gender Equality Leader in Government Time. Mexico’s advances in women's representation have roots in events that occurred in the 1990s, when the country’s 71 years of one-party rule under the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) began to come to an end amid corruption scandals and economic crises. In the aftermath, many Mexicans felt eager for political leadership that was vastly different from what they had experienced before.

Uno contra la bestia Sin Embargo. Roberto Canseco enfrentó a comando que allanó Embajada de México, ¿quién es? |

|

|

|

|

The Mexico Solidarity Project brings together activists from various socialist and left organizations and individuals committed to worker and global justice. We see the 2018 election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as president of Mexico as a watershed moment. AMLO and his progressive Morena party aim to end generations of corruption, impoverishment, and subservience to US interests. Our Project supports not just Morena, but all Mexicans struggling for basic rights, and opposes US efforts to undermine organizing and Mexico’s national sovereignty.

Editorial committee: Meizhu Lui, Bruce Hobson, Agatha Hinman, Victoria Hamlin, Courtney Childs, Susan Weiss. To give feedback or get involved yourself, please email us! |

|

Subscribe! Get the Mexico Solidarity Bulletin in your email box every week. |

|

Web page and application support for the Mexico Solidarity Project from NOVA Web Development, a democratically run, worker-owned and operated cooperative focused on developing free software tools for progressive organizations. |