|

|

|

|

The weekly newsletter of the México Solidarity Project |

|

|

|

Online at mexicosolidarityproject.org |

|

October 5, 2022/ This week's issue/ Meizhu Lui, for the editorial team |

|

|

Win McNamee/Getty Images |

|

Elections, Zapatismo, and Visions of Democracy |

|

In the United States, we’re now approaching this year’s mid-term elections — with considerable trepidation.

Our loudest cheerleaders have long insisted that our US electoral system rests on a cornerstone of “democracy.” But that cornerstone, in practice, has regularly had the consistency of sand. Rules that discourage and stop people of color from voting, gerrymandered districts, and the flat-out rejection of legitimate election results have far too often made a mockery of “representative government.”

US officials, meanwhile, regularly bless the outcome of elections in other countries if the winners figure to play nice with US corporate interests. Just as regularly, the US has greeted left-leaning election winners with cold shoulders and much worse, everything from arming insurrectionists to orchestrating assassinations, all, of course, in the name of protecting “democracy.” Think Chile under Nixon, Honduras under Obama, Bolivia under Trump, to name just a few. The United States has essentially taken a Trumpean attitude to other nations’ elections: Only the votes we like count.

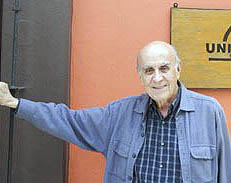

Right before the 2020 US presidential election, we asked Gustavo Esteva, the veteran Mexican activist/scholar/philosopher, about the Zapatista approach to choosing leaders. Esteva brought a fascinating background to our interview. Once an up-and-coming IBM exec and then a high-ranking official with Mexican president Luis Echevarria in the 1970s, Esteva had become disillusioned at the damage capitalist development projects were doing to the lives of Mexican peasants. He retreated into academia and then later emerged as an activist when the Zapatistas appeared on the scene.

As a leading theorist of Zapatismo, Esteva would help educate Mexican youth in both new and traditional approaches to land management and act as a trusted advisor to the Zapatista Army during its negotiations with the Mexican government. His work described how the Zapatistas were adapting indigenous governance practices that go back millennia.

Gustavo Esteva passed away unexpectedly this past March. His most essential lesson for us today? Esteva didn’t ask us to reproduce the past or simply replace elections with popular assemblies. He helped us understand a deeper reality: that we can’t experience real democracy without dismantling the capitalist relations that give the few so much power over the many. We remember him with respect, gratitude, and affection. His visionary voice will be missed. Gustavo Esteva, !Presente! |

|

|

|

Don’t miss an issue. Subscribe to the weekly México Solidarity Bulletin! |

|

|

|

|

Gustavo Esteva: Who Should Lead Us? |

|

The grandson of a Zapotec Indian, Gustavo Esteva found himself enlisted as a young man in the project of “Americanizing Mexico.” But he would opt instead to help Indigenous peoples, campesinos, and marginalized urban dwellers follow their own paths. Esteva found his political home when the Zapatistas rose up, and he would go on to establish the Universidad de la Tierra in Oaxaca, a place where he explored with indigenous people how best to build communities of health, dignity, and peace. Esteva passed away earlier this year, at age 85, and the interview he gave us nearly two years ago, in one of our earliest issues, remains an excellent introduction to his work and thought. |

|

|

US-style “democracy” — government “of, by, and for the people” — has always been the biggest US political export. Does the real product match what the advertising promises?

Gustavo Esteva: What has been happening in the US since Trump’s election offers a dramatic lesson for millions of people around the world. The US gave modern shape to the political form of capitalism, the “democratic nation-state.” Today, it is impossible to believe that government “of, by and for the people” is consistent with a capitalist economy. Instead, we see the perpetuation of the power of a self-appointed elite, now requiring increasingly authoritarian control over the people.

Elections have become the centerpiece of this US model of “democracy.” The Zapatistas and other indigenous peoples reject electoral politics. How then do they choose their leaders?

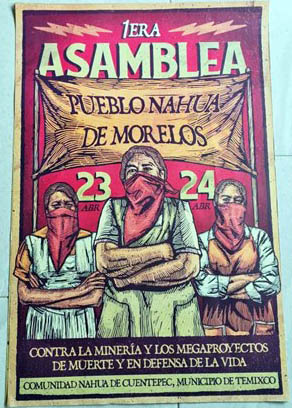

Indigenous communities have never seen the electoral process as an appropriate way to express the collective will. They don’t believe the elected officers in México really represented them. For centuries, these communities have viewed assemblies as their supreme authority. |

|

These assemblies appoint municipal officers, chosen only from among those who have performed well in serving the people of their villages, without payment, for most of their lives. The procedure can evolve in different ways. One example: In January, those qualified are identified. Informal discussions over the next few months will eliminate candidates for various reasons. By October, the village will have arrived at a consensus on the person most suitable to serve. A final assembly will ask that person to lead the village.

Custom holds that those chosen must demonstrate their humility by first protesting before finally giving in.

Individuals don’t decide to run for office. The community imposes leadership. And the leader/servant can be removed by the assembly at any moment. |

|

|

Do women have an equal voice?

The combination of old patriarchal traditions with modern sexism became unbearable for women. Their courageous actions have been transforming political life in many regions. Over the last ten years, that transformation has opened to women assemblies and positions of government that had been closed off for centuries. |

|

In one community, Lachatao, the men in government called the women and told them: “We, the men, have been doing many wrong things in our community. We now want you, the women, to take all the political power to do something else.” And the women have led impressively.

Many of us have heard about the Zapatistas in Chiapas and their autonomous government. Have these self-governing units extended beyond Zapatista territory? |

|

|

The Zapatistas’ First International Gathering of Women Who Struggle in 2018 brought together thousands of women from each autonomous Zapatista caracol, 27 Mexican states, and over 50 nations to learn, play, and dance! |

|

The Zapatista regime includes hundreds of communities and has introduced many improvements in the course of its 26 years of existence. We can describe hundreds and even thousands of communities in Oaxaca — and some in other provinces —as caracoles, with no political parties, no elections, only governing assemblies. One measure of their success has been their response to Covid. These caracoles have focused on healthy local foods and banned junk food, closing their communities to outsiders, and giving special attention to the old and those with health issues. These communities have had lower death rates than the rest of the country.

Can these caracoles — networks of resistance and autonomy — grow within the belly of capitalism and birth a new world order?

Even in the US, social experiments aimed at going beyond the very undemocratic “democratic way” — without falling into new forms of despotism — have been taking place. They’ve taken inspiration from the example of Indigenous communities in countries like México. These indigenous communities don’t oppose change, but they do oppose imposing changes that do not grow from a people’s experience. We shouldn’t see the Zapatista form of government as “the” model, since this form grows from their own local traditions.

The Zapatistas envision, as they say, “a world within which many worlds can be embraced.” |

|

|

The Necessity of Standing Strong with Puerto Rico |

|

Chican@s, Aztlanec@s, Mexican@s, time for our strongest solidarity with the people of Puerto Rico! Hurricane Fiona last month devastated the island, just four years after Hurricane Maria nearly destroyed it. |

|

But Fiona rates as more than just a natural disaster. This disaster comes, in part, “made in the USA.” How so?

After Hurricane Maria, Puerto Rico began an orgy of privatization to service its colonial debt. Included in this massive privatization: the island’s electrical grid, core infrastructure that collapsed when Hurricane Fiona hit. |

|

|

Chicanos like me relate to this history all too well, mirroring, as it does, what the US did to México, stealing that nation’s vast northern territories in the 1840s and turning the Mexicans who had lived in those areas for centuries into the oppressed nation we call Aztlan. And the US has plundered the vast mineral and agricultural resources of Aztlan just as the US has plundered Puerto Rico, all the while turning México into a neo-colony and extracting similar levels of super-profits from Mexico’s natural and human resources.

Poverty, poor housing, economic and racial inequality, corrupt puppet governments: Our peoples have all suffered much the same losses.

The valiant Puerto Rican people know not to wait for the US or their colonial government to save them. They are working collectively to restore the electrical system, to restore the water supply, to feed and shelter the elderly, the sick, and the young.

But that doesn’t mean these Puerto Ricans don’t need our support. Those who understand them best should be leading the solidarity. In the US, Chican@s and our allies can demand that the Biden Administration prioritize assistance and support to Puerto Rico, working closely with the islands’ unions and mass organizations. In México, the social movements can also call on the AMLO administration to help their sister nation. And, of course, our people-to-people donations channeled through the trusted community organization VamosPR can and will make a difference.

Compas, vamos por Puerto Rico! |

|

Bill Gallegos, a veteran Chicano |

|

|

|

Recent news reports and commentaries, from progressive and mainstream media,

Alberto Fajardo, Roberto Ramirez, and Josue Gonzalez, Boon or threat? México City wrestles with influx of remote US workers, Reuters. A wave of international visitors has poured into México City’s cafes, parks, and AirBnbs as they work untethered from daily office commutes. This digital nomad influx is exacerbating inflation and transforming neighborhoods into exclusive expatriate bubbles.

David Brooks, Echeverría comparte culpa por Tlatelolco, La Jornada. Luis Echeverría Álvarez “comparte gran parte de la culpa” por la violencia en Tlatelolco el 2 de octubre de 1968, concluyó la CIA en 1971, mientras otros documentos oficiales secretos estadunidenses revelan el seguimiento de Washington de sus esfuerzos para “cooptar y controlar” el movimiento estudiantil.

Kurt Hackbarth, AMLO Is Calling for Peace in Ukraine, but More Military in México. Jacobin. Unlike most world leaders, Mexican president López Obrador has called for a peace commission in Ukraine, stressing the need for open negotiations to end the war. But at home he has increased the power of the military.

J. Jesús Esquivel, Estábamos preparados para fallo a favor de fabricantes de armas; apelaremos: Ebrard, Proceso. Marcelo Ebrard dijo que ya estaban preparados para el fallo de la Corte Federal de Boston, que desestimó la demanda del gobierno de México contra fabricantes de armas de Estados Unidos, y usarán los argumentos del juez para apelar.

Maya Averbuch, Students’ Massacre Casts Long Shadow on AMLO’s Bid to Boost Army, Bloomberg. New revelations about the role of Mexico’s military in one of the country’s most horrific massacres is complicating President Lopez Obrador’s push to put the army at the center of his security strategy.

Guacamaya: los hackers feministas contra la militarización en América Latina, Aristegui Noticias. En un comunicado de prensa para dar a conocer su existencia y reivindicar los hackeos a las fuerzas armadas de Colombia, Chile, Perú, El Salvador y México, los integrantes de este colectivo apelan al feminismo, el anarquismo y la historia precolombina para llamar a desmantelar los Ejércitos de la región.

Julian Assange’s Family Receives Keys to the City in México, TeleSUR. During a ceremony held in the Mexican Senate, Julian Assange's father said that the example of Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who offered asylum to Assange, “will resonate around the world.”

El Presidente no es paciente grave, sus padecimientos están controlados, SinEmbargo. El especialista en salud pública Héctor Frisbie ha asegurado que los padecimientos del López Obrador no son un “cóctel de riesgo” luego de que se diera a conocer el estado de salud del mandatario tras un ataque cibernético a la Secretaría de la Defensa Nacional.

México president says dozens of companies owe a total $4.9 billion in taxes, Reuters. AMLO has vowed to crack down on tax evaders. International organizations have called some of his tactics, such as promises to criminally prosecute company attorneys, an overreach.

Sharon Sustaita, ¿Habrá reconciliación? Líderes de Va por México se reencuentran en investidura de Tere Jiménez como gobernadora, stpnoticias. Tere Jiménez se convierte en la primera gobernadora de Aguascalientes y en la primera en reunir a los líderes de la alianza Va por México. |

|

|

The Mexico Solidarity Project brings together activists from various socialist and left organizations and individuals committed to worker and global justice who see the 2018 election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as president of México as a watershed moment. AMLO and his progressive Morena party aim to end generations of corruption, impoverishment, and subservience to US interests. Our Project supports not just Morena, but all Mexicans struggling for basic rights, and opposes US efforts to undermine organizing and México’s national sovereignty.

Editorial committee: Meizhu Lui, Bruce Hobson, Bill Gallegos, Sam Pizzigati, Courtney Childs, Victoria Hamlin, Agatha Hinman, Steven Hollis. To give feedback or get involved yourself, please email us! |

|

|

|

Web page and application support for the México Solidarity Project from NOVA Web Development, a democratically run, worker-owned and operated cooperative focused on developing free software tools for progressive organizations. |