|

|

|

|

The weekly newsletter of the México Solidarity Project |

|

|

|

Every issue archived online at mexicosolidarityproject.org |

|

October 12, 2022/ This week’s issue/ Meizhu Lui, for the editorial team |

|

|

Building Our Movement: Lunch-Break Lessons |

|

I love people who harness themselves, an ox to a heavy cart, who do what has to be done, again and again.

In these lines from her memorable poem To Be of Use, Marge Piercy captured the essence of a rank-and-file union activist. Years ago, as a hospital food-service worker, I became one of those activists. I still remember the small daily conversations that made me an organizer. One in particular: Co-worker Bessie and I were finishing our break, with just five minutes left before time to start serving lunch in the cafeteria, when a doctor came up to the counter and rapped on it to get our attention: “I’m in a hurry!”

“We better go serve him,” said I, having been raised to see doctors as only a few ranks down from the gods.

“Doctors always keep me waiting,” Bessie replied. “He can wait until we finish our break.”

Bingo, class consciousness! From an individual action to maintain our right to a full break, we would go on to organizing mass actions to expand the rights of all workers.

Long-time union activist Frank Martin del Campo has done, again and again, what has to be done to get the labor movement out of Marge Piercy’s mud. And nothing may need doing more, he reminds us in this week’s issue, than solidifying ties between US rank-and-file and Mexican rank-and-file workers.

The United Auto Workers could play a key role in that effort, and a more progressive leadership at the UAW could make all the difference in the world. A vote for the UAW’s national officers is coming up, and our México Solidarity Project has been working with UAW retirees — a huge section of the union’s voting membership — to distribute a “get-out-the-vote” letter that urges support for the progressive UAW Members United slate.

Every union supporter, whether a UAW member or not, has a stake in this election, and you can help “move things forward” by “forwarding” our letter through your networks! This link to our letter also allows retirees to sign on to México Solidarity Project updates. Thanks! |

|

|

|

Don’t miss an issue. Subscribe to our weekly México Solidarity Bulletin! |

|

|

|

|

The Importance of Rank-and-File, Bottom-Up Unionism |

|

Frank Martin del Campo’s “rank and file” mantra grows from his formative experience as a founder of the R & F Caucus in the Retail Clerks union, an effort that transformed his local into a democratic and militant one. At Solar Turbines, he would later found an R & F Machinist Action Committee to stop black/brown discrimination. That group’s fighting spirit revitalized a demoralized local. And both those efforts represented just the beginning! Now living in Oakland, Frank Martin del Campo maintains his roots in Jalisco México. He co-chairs the México Solidarity Project/Labor Notes SINTTIA Support Committee. |

|

|

Why did your parents come to the US? Did they influence your political development?

My grandparents lived in rural Jalisco, where armed rebellions devastated the countryside after the 1910 revolution and scattered my family. My father would be on the first train to the US in 1942 when the bracero program started. But he deserted after getting disgusted with topping beets and broke his “contract” with the company. Maybe I get my refusal to put up with exploitative conditions — for any worker — from my father’s disgust.

In 1967 I was drafted. I was patriotic, in officer training, and about to go to Vietnam. But then I met returning vets, and they turned me around 180 degrees. I became anti-war, discovered Chicanismo, and became a revolutionary nationalist. But the labor movement became where I found my home.

You became a rank-and-file activist, right?

I cut my teeth working at Safeway. In 1972, I helped found the Rank and File Organizing Committee in my 10,000-member local, After a few years, we succeeded in a complete take-over of the union leadership. Our platform included international issues. We demanded, for instance, no US intervention in Angola. Our victory didn’t sit well with the union bureaucracy, and they put our local into receivership.

After 18 months we won the right to another election — and swept into office again! But the union office and the staff had become our focus, and we failed to stay rooted in the rank and file, one of my biggest lessons.

And then you worked in auto, right?

By then I had become a member of a left organization that sent me to work in auto. I got a job at GM’s South Gate plant near Los Angeles in about 1977. At that time the powerful UAW ran the plant. We workers didn’t know who the plant manager was, but we sure knew our union rep.

Our chief steward Sal Astorga walked through the plant like a military general in full UAW regalia. We all trembled beneath his feet. Everyone knew his power and influence in the plant, and he was also a heavy hitter on the national bargaining team. We didn’t fear him. We loved him. Everyone knew he was our guy. Period.

What’s happened to auto workers in the US since that time? |

|

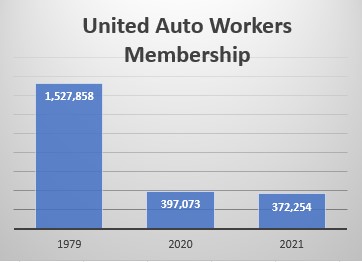

My GM South Gate plant shut down and moved to Oklahoma in 1983, where the UAW had little strength. In the 1980s union membership began dropping like a rock, soon down a third from the 1.5 million UAW members in 1979. Reaganomics hit us hard. Reagan stopped honoring the unwritten labor contract of the 1950s: In an expanding economy, US labor made a pact with the devil, trading union militancy for a promise of a share of the spike in corporate profits. Then labor found itself caught with its pants down when the devil collected his due. |

|

|

The UAW, in the new climate, started to make concessions. The first: making the probation period for new workers 90 instead of 30 days. Concessionary contracts would become the norm. Drastic cuts in union power meant drastic cuts in benefits. No more Sal Astorgas. Kiss-ass climbers out for themselves took the place of the likes of Sal.

Then, in 1994, the North American Free Trade Agreement took effect. This opened the borders so that US auto companies became “free” to go further south, down to México, for even cheaper labor and unions easy to buy off. UAW membership plummeted again. By the end of the decade, membership had dropped to less than 700,000. Today, the UAW has under 400,000 members in the US, many of them not in auto, but in health care, gaming, and universities. |

|

We saw a huge upsurge against “free trade” in Seattle in 1999. But labor backed off. Why?

The sax! President Clinton got out his sax, and union leaders sat down to listen. Labor has been too close to the Democratic Party for its own good.

We’ve also seen the bureaucratization of the labor movement, with a shift to a focus on national negotiators and staffers rather than on educating and mobilizing the rank and file. Things start falling apart when a disconnect between the leaders and the base starts growing. |

|

|

Photo: In These Times |

|

Today, you’re co-chairing the joint México Solidarity Project/Labor Notes México labor support committee, with a focus on auto. Why auto?

Auto has become the major industry and a key economic driver in all three USMCA countries. And in México auto ranks as the sector most on fire with independent union organizing, with five major recent rank-and-file victories and counting. The wage and benefit increases these new unions win can begin to reverse the race to the bottom.

Mexican workers also understand internationalism. Workers at the GM plant in Silao, before they won their own battle, engaged in support actions for striking John Deere UAW workers in the United States. We see real break-through possibilities in the auto sector.

Internationalism has largely disappeared from what we hear from labor. What can be done to change that?

We hear more about international labor issues from fair-trade folks than from our labor leaders. It’s great to address international trade issues as opportunities to push for labor rights around the globe. But we have no substitute for democratic worker-to-worker and democratic union-to-union relationships.

US labor unions too often confine their vision to their own shop, union, or country, rather than raising their eyes to see the big picture. Labor can’t stop the shedding of jobs through “protectionism” and blaming foreign workers. We can only improve our jobs here in the US by fighting to improve the jobs of workers overseas.

Solidarity must begin at the base. Many labor leaders talk like lawyers — and timid ones at that! To mobilize workers, we need the raw, unfiltered speech of conscious militants who come from the rank and file. This will always be crucial, for creating not a spontaneous movement, but one based on class consciousness and an understanding of capitalism. Democratic unionism will also be critical, but also always the floor and not the ceiling.

You emphasize worker-to-worker solidarity. What can we do?

Our Committee supported the Mexican independent union SINTTIA by asking local unions and other community groups to write to GM CEO Mary Barra to ensure fair contract and representation elections. Then Labor Notes brought one of SINTTIA’s rank-and-file organizers to speak to the thousands of rank-and-file workers at its 2022 national conference. We made sure that Mexican activist Israel Cervantes met the folks most important to SINTTIA’s struggle, particularly folks in the UAWD — the Unite All Workers for Democracy — the UAW’s progressive wing.

We pushed for the UAW to invite SINTTIA to speak at its convention, to no avail. That’s why we’re now working to get out the retiree vote, a huge bloc, for the Members United slate that will build international solidarity. Next steps? Worker-to-worker trips, political education, strengthening cross-border organization. México’s labor movement is sitting at a turning point. Can US labor match its progress? |

|

|

José Arenas: On Place and Belonging |

|

Jose Arenas, the director of Taller Arte del Nuevo Amanecer in Woodland, California, knew what he wanted from a young age. The son of migrants who worked in fields and canneries and traveled between Guadalajara and San Jose, Arenas learned from his mother’s various creative pursuits, everything from quilt making to embroidery. |

|

|

Arenas went on to study at the San Francisco Art Institute and get his MFA at UC-Davis, where he had as his mentor Malaquias Montoya, an iconic Bay Area Chicano artist.

“I love that I can engage with people on creative and collaborative projects,” notes Arenas, “but then I also love the solace of the studio and working things out in my own artistic space.”

The paintings and prints of Arenas — modern and traditional, quiet and loud, personal and global — call us to remember the commonplace objects that we ourselves cherish as “mementos” of our own pasts. Below, some more thoughts on his work, from Arenas himself. |

|

|

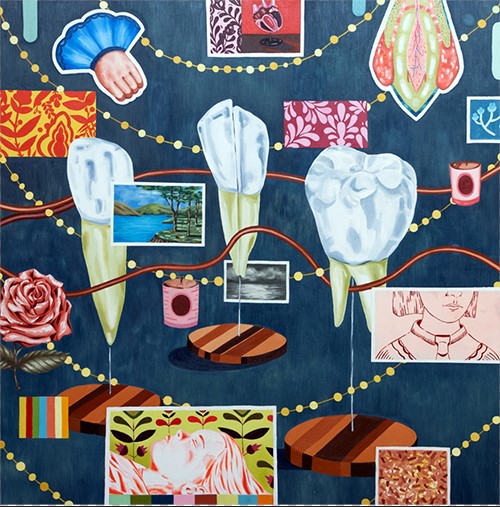

I use symbols that speak to the experience of loss and searching for place and belonging (Many Ways Home). I started collecting those things, those symbols, that made up such a rich part of my environment, decorative elements very distinctly Mexican (Casa Calli). |

|

|

|

Many Ways Home/2017 Casa Callit/2019 |

|

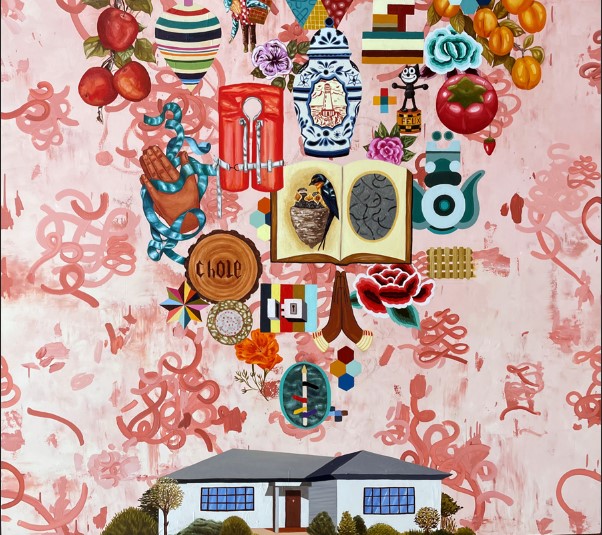

I was using birds as symbols for north/south migration patterns, travel, nautical symbols — all in older work. Now they fit into a new narrative (Gone/Changes).

In my latest work, I use recognizable images as an anchor for the things that represent home and have personal meaning, those little mementos I carry with me that relate to my mom’s creative practice but also to a long precolonial tradition with indigenous connections as well. All Things Big and Small juxtaposes my childhood home in San Jose with a murmuration of symbols that rhythmically hover and float above. Like other works, it signals what place and home mean to me. |

|

|

|

Gone/Changes/2019 All Things Big and Small/2022 |

|

Activist Vicky Hamlin, a retired tradeswoman, |

|

|

|

Recent news reports and commentaries, from progressive and mainstream media, on life and struggles on both sides of the US-México border |

|

Raghu Gagneja, US federal judge dismisses México’s $10B lawsuit against US gun manufacturers, Jurist. The Mexican government had brought the lawsuit against seven US gun makers and one gun wholesaler for a wide variety of practices that knowingly facilitate trafficking of guns into México.

Sheinbaum termina gira de informes por su cuarto año de gobierno, Animal Politic. “Cambiamos la forma de gobernar. La corrupción, la hipocresía, el odio, la exclusión, el racismo y el clasismo son rechazadas por la gran mayoría de los habitantes de nuestra ciudad”, dijo la jefa de gobierno de la Ciudad de México.

Youyou Zhou, The power of Hispanic voters, in 10 charts, Vox. Hispanic voters could swing the 2022 midterms.

Diputada trans María Clemente García propone que trabajo sexual sea actividad lícita, Aristegui. En conferencia, propuso reformar la Ley Federal de Trabajo para que se garantice la seguridad y bienestar social de quienes ejercen este oficio.

Mexican tax chief Raquel Buenrostro named as next economy minister, Reuters. The head of the country's tax authority made her name cracking down on big business for unpaid taxes.

Tamara Mares Rivera, La “Dama de Hierro” apretó a empresarios; ahora debe acercarlos y resolver el T-MEC, SinEmbargo. Raquel Buenrostro, cercana al Presidente Andrés Manuel López Obrador y extitular del Servicio de Administración Tributaria, se enfrentó a empresas extranjeras como Coca-Cola y Walmart y logró que pagaran impuestos en tiempo récord.

Luis Rojas, Inflation in México has topped out, says president, MSN. The Mexican government has also announced the extension of an agreement with the private sector that seeks to contain inflation, especially in foodstuffs such as corn.

Dulce Olvera, Los meses de escalada de precios forzaron a muchos mexicanos a modificar sus dietas, SinEmbargo. El nuevo Acuerdo del Gobierno federal con la agroindustria busca reducir el precio de la canasta básica de 24 productos de 1,129 pesos a 1,039 pesos promedio hasta el 28 de febrero de 2023.

Christopher Lenton, México, Trading Partners in ‘Productive’ Dialogue Amid Talk of Energy Export Bans, Natural Gas Intelligence. Observers see a noticeable change in tone recently as México, the United States, and Canada work to support regional trade opportunities in light of the war in Europe and the general breakdown of supply chains post-pandemic.

Mathieu Tourliere, Sedena Leaks: Gobernadores, senadores, diputados y alcaldes de Morelos ligados al narco, Proceso. Informes de la Sedena y la Marina filtrados por el colectivo Guacamaya vinculan al círculo cercano de Cuauhtémoc Blanco, a "autoridades del exgobernador de Morelos Graco Ramírez", senadores, diputados, alcaldes y jueces con grupos del narcotráfico. |

|

|

The México Solidarity Project brings together activists from various socialist and left organizations and individuals committed to worker and global justice who see the 2018 election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as president of México as a watershed moment. AMLO and his progressive Morena party aim to end generations of corruption, impoverishment, and subservience to US interests. Our Project supports not just Morena, but all Mexicans struggling for basic rights, and opposes US efforts to undermine organizing and México’s national sovereignty.

Editorial committee: Meizhu Lui, Bruce Hobson, Bill Gallegos, Sam Pizzigati, Courtney Childs, Victoria Hamlin, Agatha Hinman, Steven Hollis. To give feedback or get involved yourself, please email us! |

|

|

|

Subscribe! Get the México Solidarity Bulletin in your email box every week. |

|

|

|

Web page and application support for the México Solidarity Project from NOVA Web Development, a democratically run, worker-owned and operated cooperative focused on developing free software tools for progressive organizations. |