|

|

|

|

The weekly newsletter of the México Solidarity Project |

|

|

|

Every issue archived online at mexicosolidarityproject.org |

|

November 2, 2022/ This week’s issue/ Meizhu Lui, for the editorial team |

|

|

Ricardo and Enrique Flores Magón |

|

Why We All So Need To Become Magonistas |

|

Our interviewee this week, activist academic Christina Heatherton, has a name for the places that see people from all over the world suddenly thrown all together. She calls these places “convergent spaces.”

In the fields of California, for example, Chinese came first to occupy the region’s low-wage jobs. Japanese, Filipino, and Korean workers soon followed, both voluntarily and involuntarily. Mexicans fleeing across the border from poverty and unrest also found that farm stoop labor offered the only jobs available.

Convergent spaces can make fertile ground for multinational organizing. But that organizing doesn’t come automatically. The rich and powerful, after all, have been using race to “divide and conquer” as long as we’ve had a United States. How can we best overcome that division? Heatherton shows us how in her just-published new book. She brings us the story of the Mexican revolutionaries Ricardo and Enrique Magón.

The Magón brothers helped form the first US multinational union, the IWW, and the IWW succeeded where nationality-based labor organizations had failed. Ricardo Magón reminded US workers that they had much to learn from exiled Mexican revolutionaries like himself and his comrades, people who organized in whatever country they found themselves in, who risked imprisonment and death for oppressed workers anywhere and everywhere.

US organizers soon found that Magón’s words rang true. In 1921, on a visit to México City, radical labor organizer Mother Jones saw Mexican workers carrying a banner supporting the US Haymarket labor martyrs. An amazed Mother Jones called that the most remarkable demonstration of solidarity she had witnessed in all her years of industrial conflict. In the 1940s, Dorothy Healey, a well-known left activist, credited her international consciousness to the Mexican cannery workers she organized among.

We still today have much to learn from activists in México, both those who broke the political stranglehold of the neoliberal party in power and those social movement activists who take to the streets demanding more action from the new progressive party now in power. And if we learn their lessons and resist division by nationality, we can make gains for workers all over the world. May we all become Magonistas! |

|

|

|

Don’t miss an issue. Subscribe to our weekly México Solidarity Bulletin! |

|

|

|

|

‘Workers of America! Have we Mexicans no message for you?’ |

|

Christina Heatherton teaches American studies and human rights at Trinity College in Connecticut. For two decades she has been working with social movements to produce collaborative works of political and popular education. Her latest book, Arise! Global Radicalism in the Era of the Mexican Revolution, brings to light how activists worldwide gained inspiration just over a century ago from revolutionary México. She earlier co-edited Policing the Planet: Why the Policing Crisis Led to Black Lives Matter.

Your family is Japanese-Okinawan. So what sparked your deep interest in Mexican revolutionaries? |

|

|

My Okinawan great-uncle came to the United States via México and became a labor organizer in the fields of California’s Imperial Valley, a place where Okinawan, Japanese, Chinese, Black, Filipino, South Asian, Indigenous, poor white, and Mexican workers all labored together. These communities saw FBI raids even before Japanese and Okinawans were forced into internment camps during WWII, and labor organizers were among the first to be targeted. Federal agents showed up at my great-uncle’s door, but, according to my uncle, his father “had been down fighting with Pancho Villa, so he knew how to take care of business!”

I had never considered how the radical resistance of Okinawans and Japanese in the United States might have been forged through their affinity with other people, namely Mexican peasants during the Mexican Revolution. That made me want to explore the global connections between the common people who make history.

The Mexican Revolution evolved mainly as a peasant-based struggle for land and freedom, but the Magón brothers saw workers as foundational to the struggle. What did they do?

Ricardo Flores Magón and his brother Enrique grew up in a fiery period of revolts against Porfirio Díaz’s government. They saw the need for revolutionary change. Influenced by the local traditions in Oaxaca where they grew up, their Zapotec lineage, and the circulation of global revolutionary thought, they developed their own radical theories of anarcho-communism and became leading anarchist agitators. Ricardo’s first arrest came in 1892 at a student protest. That arrest sparked a life of organizing, in and out of prison, and constant surveillance from the Mexican and US governments. |

|

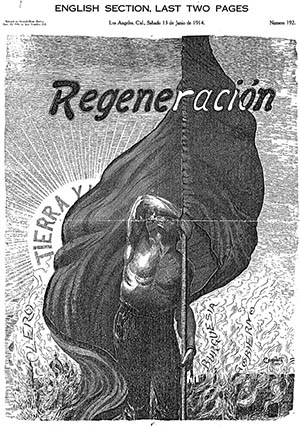

Ricardo wrote for and published the radical newspaper Regeneración and later became a leader in the Partido Liberal Mexicano. The PLM played key roles in labor struggles during the lead-up to the Revolution, including the 1906 Cananea mineworkers strike in Sonora the 1907 Río Blanco textile workers strike in Veracruz.

Magón successfully appealed to working-class people to join the revolution, and that made him “an enemy of the state.” The Magónes had to flee to the United States, constantly moving ahead of their pursuers, to San Antonio, St. Louis, and Los Ángeles. The PLM was also organizing US workers, playing significant but largely unrecognized roles in building the Western Federation of Miners and the Industrial Workers of the World, the IWW. |

|

|

“Workers of America! Have we Mexicans no message for you?” Ricardo Magón wrote in 1914. “Do you suppose that we, over whose wealth of mine and field and forest the earth’s money-lords have warred, do not comprehend the capitalist system, or that, until we have read Karl Marx, we can be robbed of surplus value without being aware of it?”

Your new book develops the key concept of “convergent spaces” where international solidarity gets forged. Can you explain?

“Convergence spaces” are sites where people of different backgrounds and radical traditions were compressed, forced to interact, and, as a result, were able to make new meaning of their lives in struggle. Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary in Kansas offered one example. |

|

During World War I, many anarchists, socialists, communists, pacifists, and nationalists were convicted under new US federal laws like the Espionage and Sedition Act, including the Magón brothers, and sent to Leavenworth. These incarcerated activists transformed the prison into a so-called “university of radicalism,” a school for political education and revolution. They organized their own university, offering regular lectures and classes to each other. |

|

|

Ricardo Flores Magón. Photo: Mexicanist |

|

Records reveal the astonishing number of international magazines and journals the prisoners ordered. Prisoners also ordered many foreign language dictionaries since people spoke so many different languages and were also trying to teach and learn new ones.

The prisoners also traded books. For example, Six Red Months in Russia, a reflection on feminism by socialist Louise Bryant, had a long line of people eager to read it. People sentenced to Leavenworth as “criminals” often left as organizers, steeped in the internationalism they experienced first-hand in the penitentiary.

You note that many revolutionaries became activists not just in their own countries.

At the turn of the century into the early 20th century, everything from colonial dispossession and imperial rule to military aggression and capitalist immiseration were constantly forcing people to move. That movement produced astoundingly unanticipated alliances and political formations.

Ho Chi Minh, for instance, became a founding member of the French Communist Party in Paris before becoming one of the fiercest opponents of French colonialism and US imperialism in Vietnam. Japanese revolutionary Sen Katayama, a key opponent of Japanese imperialism and a founding member of the Communist Party USA, became beloved by Black radicals in the United States who saw in him a fighter against racism and white supremacy. |

|

M.N. Roy, a staunch opponent of British colonialism in India, ended up in México seeking arms and support for the Indian anti-colonial struggle and began sympathizing with the Revolution there.

In México, “the land of my rebirth” as he called it, Roy became a founding member of the Mexican Communist Party. |

|

|

Photo: The Indian Express |

|

The global movement of capital produced its own contradictions. Tracing activist movements allows us to comprehend an alternate formation of internationalist traditions from below.

We’re seeing growing interest and scholarship in understanding how México has influenced US radical history, with your book as an outstanding example.

Understanding the 20th century requires a more global understanding of the Mexican Revolution. As scholars like Gilbert González have argued, México was annexed twice over: first in 1848 with the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo when the United States annexed one-third of Mexican territory. Subsequently, dramatic foreign investment informally annexed the remaining land. The US became a creditor nation for the first time in relation to Mexico.

By the outbreak of the Mexican Revolution, a quarter of all US investments lay in México, with US investors owning over 80 percent of Mexican mineral rights and over 22 percent of Mexico’s surface. The Revolution often gets understood as a contained nationalist event. But it’s hard to envision internationalist opposition to US hegemony arising without it.

Finally, I’ll say that we sometimes see “solidarity” as charity people in the United States grant to other people’s struggles. But people in the US, at this moment, are looking outside their country, particularly to the fierce leadership shown by Mexican feminists who are boldly and unapologetically fighting for all forms of bodily autonomy.

These feminists are also concretely helping people in the US fight repressive laws and gain access to reproductive care. Their work shows that international solidarity is less something we offer and more something we build together.

Interested in reading Christina Heatherton’s just-published new book, Arise! Global Radicalism in the Era of the Mexican Revolution? At the University of California Press website, México Solidarity Bulletin readers can now pick up a copy for 30 percent off with the promo code “21W2240.” |

|

|

Some Observations on Art and Its (Mis)Use |

|

I saw an article in Hyperallergic a few weeks ago about this guy who supposedly burned a Frida Kahlo drawing so he could sell digital reproductions — NFTs — of the piece and make a ton of money. No one seems to know if the drawing he burned really came from Kahlo, but the burning has blown up as the art stunt of the year. |

|

Another article in T Wanderlust, a new travel newsletter from the editors of the New York Times T Magazine, also caught my eye, with the headline, “The Central Mexican City of Morelia Is Home to Historic Monuments and Heritage Crafts.” Officials in Morelia are using art as a draw to make the city a bright, shiny new travel and living destination for gringos with dollars. |

|

|

Kind of like many other well-known Art Tourism destinations all over the globe. But is the intent here really just to support the city? This reads as a new page in the gentrification playbook to me. |

|

|

|

Above image courtesy Melike Ayan, Mel Strategies. Screenshot Elaine Velie/Hyperallergic. |

|

Every week brings bizarre new stories about the ways that art is (mis)used in the pursuit of profit. Artists moving into affordable live/work spaces are often the first signs of the bulldozers that follow. Unethical and disrespectful stunts that climb on the backs of legitimately famous foremothers and fathers have become commonplace.

Antiquities can no longer be easily stolen, but we see other more devious means to steal art. These two stories about Kahlo and Morelia make me wonder: Has México become the new exploitable art resource for Americans? México sits so conveniently, temptingly close to the Norteño art industry/factory…

If I were México, i would keep my eyes open and my profit-sniffing senses on high alert. |

|

Activist Vicky Hamlin, a retired tradeswoman, |

|

|

|

Recent news reports and commentaries, from progressive and mainstream media, on life and struggles on both sides of the US-México border |

|

AMLO defends Ayotzinapa investigation after NYT reports setbacks, México News Daily. The president said that the government would continue with its investigation and noted that it is attempting to have one key witness — Tomás Zerón, head of the now-defunct Criminal Investigation Agency when the students disappeared — extradited back to México.

Calderón: esclarecimiento necesario, La Jornada. La semana pasada ha vuelto a ponerse atención a las acusaciones de que Felipe Calderón Hinojosa es responsable por tráfico de armas de Estados Unidos hacia México y por la entrega de ellas a grupos del crimen organizado.

Mark Stevenson, In México, ruling party infighting gets worse, Associated Press. With Morena now dominant, the biggest question in Mexican politics has become what kind of internal divisions will hit the party.

Eréndira Aquino, Encarecimiento de rentas y expulsión de inquilinos en la CDMX, los riesgos del convenio entre gobierno y Airbnb, Animal Politic. Especialistas en temas de urbanidad y vivienda advierten que el impulso a la renta de corta estancia con plataformas como Airbnb incrementará los costos del arrendamiento en la capital y podría provocar la expulsión de inquilinos en zonas atractivas para el turismo.

Daniel Sánchez y Sánchez y Frida Isela Murillo Frías, México suffers from one of the highest rates of deforestation on the planet, with a third of its land area is severely degraded, Centre for Nature and Climate. Three Mexican civil society organizations are trying to drive investment in ecosystem restoration.

Obed Rosas, El INE sí violó la Ley con sus fideicomisos por cientos de millones: Auditor interno, SinEmbargo. Los recursos que se destinan al INE han sido tema de un arduo debate entre el Gobierno federal y los consejeros electorales.

México launches bid to host 2036 Olympic Games, MercoPress. Foreign Minister Marcelo Ebrard has filed the necessary paperwork before the International Olympic Committee and says the event would not entail an economic burden to the nation.

AMLO responde a declaraciones de Tatiana Clouthier: ¿Está rodeado de una jauría de perros? El Financiero. López Obrador ha respondido a las declaraciones de Tatiana Clouthier, ex secretaria de Economía, quien afirmó que AMLO está “rodeado de una jauría de perros que le llevan mentiras”.

Time’s up! México eliminates daylight savings time ending the need to change clocks twice a year, Vallarta Daily News. The AMLO government points to the science that shows the negative health impact of changing times twice a year.

Julio Ramírez e Yvonne Reyes, Retroceso democrático con reforma electoral, el regreso a 1988, Indigo. De aprobarse la reforma político-electoral propuesta en los términos propuestos por el presidente Andrés Manuel López Obrador, se corre el riesgo de retroceder más de tres décadas en materia democrática. |

|

|

The México Solidarity Project brings together activists from various socialist and left organizations and individuals committed to worker and global justice who see the 2018 election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as president of México as a watershed moment. AMLO and his progressive Morena party aim to end generations of corruption, impoverishment, and subservience to US interests. Our Project supports not just Morena, but all Mexicans struggling for basic rights, and opposes US efforts to undermine organizing and México’s national sovereignty.

Editorial committee: Meizhu Lui, Bruce Hobson, Bill Gallegos, Sam Pizzigati, Courtney Childs, Victoria Hamlin, Agatha Hinman, Steven Hollis, Betty Forrester, Daniel McCool. To give feedback or get involved yourself, please email us! |

|

|

|

Subscribe! Get the México Solidarity Bulletin in your email box every week. |

|

|

|

Web page and application support for the México Solidarity Project from NOVA Web Development, a democratically run, worker-owned and operated cooperative focused on developing free software tools for progressive organizations. |