|

|

The weekly newsletter of the Mexico Solidarity Project |

|

Every issue archived online at mexicosolidarityproject.org |

|

September 11, 2024 |

|

|

|

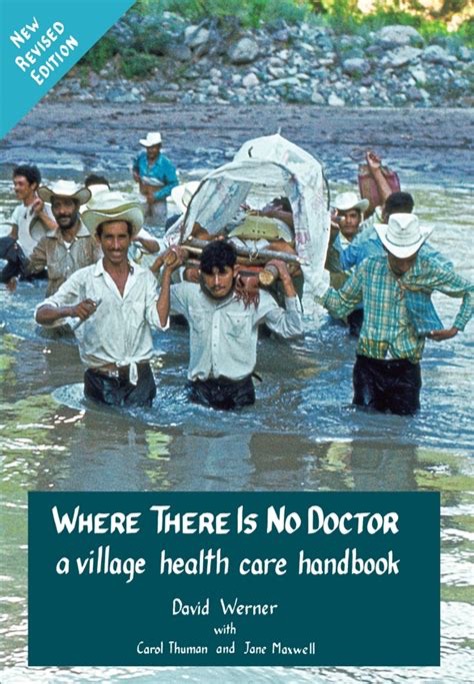

Health Care Where There Is No Doctor |

|

Bruce Hobson, for the editorial team |

|

|

Ajoya, Sinaloa |

|

Over Christmas vacation in 1965, my friend David Werner hitchhiked 1500 miles from California to Western Mexico. North of Mazatlán, he asked a truck driver, What’s in those mountains up there? Traveling up a dirt road for hours, he arrived at San Ignacio, a town above the Río Piaxtla. Hours beyond, the road ended at Ajoya, a stunning 400-year-old village at the base of the Sierra Madre. Ajoya had no electricity, the villagers drew water from a river below and, except for traditional healers, the village had no doctor.

The following year, David quit teaching and returned to Ajoya. He intended to stay a year — he stayed over fifty. In the village, he and a team of promotores de salud (health promoters) organized Proyecto Piaxtla, the clinic and training program that created a network of health outposts throughout the mountain region.

In our interview with David, he told stories of his years in the Sierra Madre. Who would know that the collection of notes and illustrations he’d penciled as basic guides for the village health team was the genesis for the book Donde No Hay Doctor (Where There Is No Doctor)? Since 1973, David’s book has been translated into over 100 languages and is used by community-based health programs in poor communities throughout the world.

I met David in the early sixties, when he taught biology at an alternative high school in northern California. It offered college-level courses, promoted learning from direct experience in the natural world, and supported activism in the civil rights and anti-war movements.

Each year David took groups of students, including myself, to Mexico on ecological field studies. Our classroom was the Pacific Ocean, the Great Sonoran Desert, the Nayarit jungle, the mountains of the Sierra Madre. Based on intensive studies of a desert oasis in Sonora, three of us kids co-authored a cover story for Natural History magazine! David Werner — who turned 90 in August — continues to write and comment on the struggles of the poor in rural Mexico, where he has lived since 1966. |

|

For a deeper dive into current news and analysis in English, check out our media website. And definitely see the new English podcast ¡Soberanía! (Sovereignty) with José Luis Granados Ceja and Kurt Hackbarth. They entertain, while dismantling the lies and distortions about Mexico fed to us by the mainstream media. |

|

Don’t miss an issue! Sign up for a free Mexico Solidarity Bulletin subscription. |

|

|

Promoting Healthcare in the Sierra Madre |

|

David Werner, author and health and social justice activist, is co-founder and director of HealthWrights and was a visiting professor at Boston University’s International School of Public Health. A biologist and educator by training, he has worked for over 50 years in village health care, community-based rehabilitation, and Child-to-Child health initiatives in the global south, primarily in Mexico. From 1965 to the 1990s, he was an organizer and advisor to Project Piaxtla, a pioneering health program run by campesinos. This program contributed to the conceptualization and evolution of primary health care (PHC) globally. |

|

|

You weren’t a doctor! What led you to work on health problems in rural Mexico?

No, I don’t have a medical background. I taught ecology in an alternative high school in California. Instead of starting with books, my classes started with field trips where students could observe for themselves and draw their own conclusions. |

|

|

David Werner & Bruce Hobson in Sierra of Jalisco, 2010

|

|

Looking for an ecologically diverse area to explore, I hitchhiked down to Mexico during Christmas vacation and hiked up into the mountains of the Sierra Madre toward villages reachable only on foot or horseback. With another school teacher, I hiked up into the high mountain area. |

|

I returned down the mountain alone. The sun was setting, and I was still a long way from the next village. As I hurried by a simple stick-wall hut, a man came out and asked where I was going. I said “Bordontita.”

“Bordontita is too far to walk in the dark, and there are snakes and scorpions on the trail! Why don’t you stay with us!” For someone from the United States, such an offer was very unexpected, and I gladly accepted. He spoke to his young son, who limped out and came back with two eggs, which they cooked for me, while the family ate just boiled beans.

After eating, everyone bedded down for the night on the dirt floor. That night, even in my sleeping bag, I was cold. But the family slept on a deer skin with only three blankets for all seven of them. That night it was so cold that by 3 a.m., the family started a fire in the middle of the floor and sat around it with the young ones in their arms until dawn.

By the light of day, I noticed the limping boy had pus coming out the side of his foot. I asked him what happened. He said he’d stepped on a thorn — three months before! |

|

|

David treating child in Sierra Madre village of Verano, 1967 |

|

I also noticed that two smaller children had large swellings on their throats, presumably goiters due to iodine deficiency, which can also cause deafness and mental slowness.

Back in California, I told my students about my experiences, and they were eager to learn more about the lives of the people I’d visited. The following spring, I took my first student group to the region. |

|

|

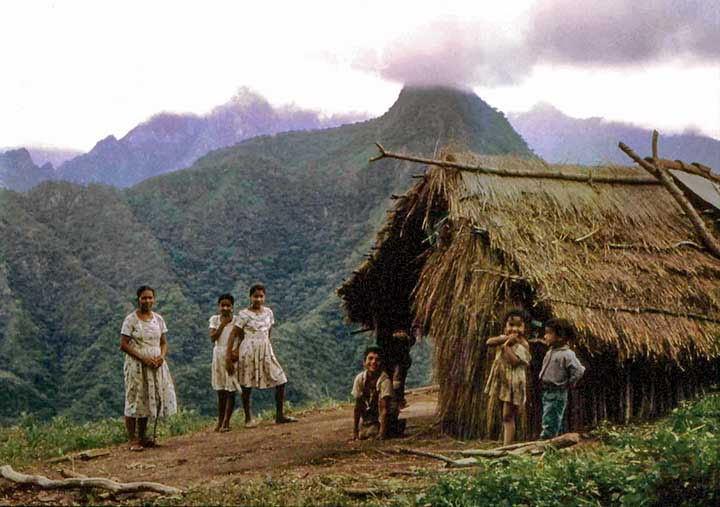

Don Esteban and family, El Pino near Verano,1967 |

|

We put together basic medical kits, and because most of the people couldn’t read, we made drawings about how to use the contents. We hiked for two weeks into the mountains, visiting many small villages.

On our hike, the villagers helped us as much or more than we helped them. In one remote village, we helped save the life of a little girl who had fallen into a fire pit. A few days later, high in the mountains, one of my students became ill with pleurisy and was almost unable to breathe. A local curandera (indigenous healer) taught us how to clear the phlegm from her lungs by having her breathe hot water vapors and likely saved her life. It was the villagers’ warmth and generosity that moved me to live with them — and perhaps contribute in some way. |

|

|

On the way to the Ajoya clinic from high in the mountains |

|

I took a year off from teaching to go back to Mexico. My idea wasn’t to play doctor but to provide health information in the language of the local people. I got some basic training from a doctor in California and moved to the Sierra Madre.

What were the main causes for poor health? What treatments did they have? |

|

The people had little or no money and almost no formal education. They had no access to antibiotics and other modern services, and although the government theoretically provided free TB treatment, it was unavailable in these villages. But the villagers did have a wealth of traditional healing skills and community spirit from which we could all learn. |

|

A fundamental cause of poor health was the inequitable distribution of arable land. While a few wealthy families owned all the most fertile farmland, most of the poor used slash-and-burn farming to grow their corn and beans on the steep mountain sides. The poor and uncertain yield of their crops led to high levels of hunger and malnutrition, particularly of children.

What did the health program look like? |

|

|

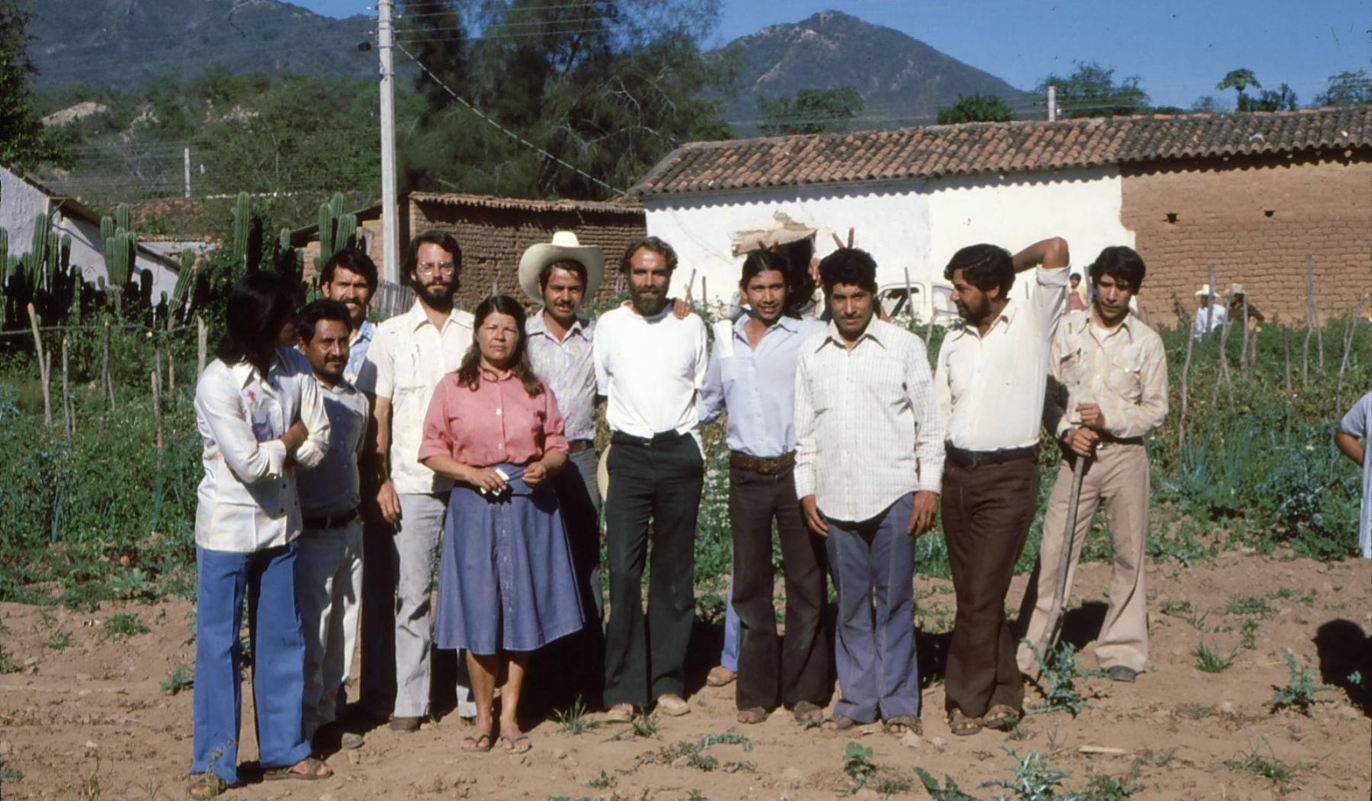

Early Piaxtla health team, 1978 |

|

The village-run health program — Proyecto Piaxtla — developed in three basic stages. The first was the focus on curative treatment of poor health. The second was on preventative care. The third was on collective political action that focused on the root causes of poor health. We began with what the people wanted most, curative care. I didn't treat many patients, but trained health workers, promotores de salud. The villagers themselves chose them and often selected local curanderas. The promotores charged little or nothing for the services, but the villagers often gave them food or helped with farming.” |

|

I began to write notes and make pencil drawings to help families in these remote areas diagnose and treat illness and injury. Those notes ultimately became the beginning of the handbook Where There Is No Doctor.

After about the first three years, we shifted our main focus to prevention. The government was supposed to provide vaccines against common diseases: polio, diphtheria, tetanus (the biggest killer of newborns), whooping cough and TB. But because vaccinations sometimes caused side effects, the villagers often rejected them. |

|

|

David' Werner, Where There Is No Doctor, 1973 |

|

So, we took action to inform the villagers about the importance of vaccinations. In one largely indigenous village, three sisters had had their ears pierced with the same thorn. Two had been vaccinated. The one who wasn’t died of tetanus a few weeks later. From this unfortunate incident, we developed a traveling theater skit to help the villagers understand the importance of vaccination. After that, people clamored for vaccinations. |

|

|

Campesino family in Sierra Madre with young disabled son |

|

The third stage was organizing political action to tackle the root causes of poor health. Through lively workshops, villagers analyzed that one of the biggest causes was inequitable land tenure.

A major issue — the rich people’s cattle were freed to eat the poor people’s crops planted on the steep hillsides. So the villagers began fencing their small farms. Then they banded together and built one fence around many plots.

As a result, Victor, one of the wealthy ranchers, went to a distant village and offered to pay someone to assassinate the organizers of the group protecting the crops. But those farmers not only refused, they told their neighbors about the plot. In response, a group ambushed Victor when he rode by on his horse and told him, “If any of us is killed, not even your dogs will survive!”

In the West, medical experts provide expensive services from the top down, which doesn’t work in rural Mexico. However, when the Sierra Madre villagers analyzed their needs and worked together, they greatly improved the health of their communities.

Within ten years after beginning the village health program, Proyecto Piaxtla, infant and maternal mortality dropped more than half. |

|

TO BE CONTINUED! |

|

The 2nd part of David Werner’s interview will focus on his work with the rehabilitation program in the Sierra Madre, Proyecto Projimo, organized by young disabled people. Coming soon. |

|

|

|

|

Tlatelolco and the Chicano Moratorium |

|

|

Bill Gallegos, a veteran Chicano liberation activist, environmental justice leader, and revolutionary socialist, has a lot to howl about. Many also know Bill for his poetry and political essays. Gallegos is a member of the editorial board of The Nation. |

|

|

Mexico’s revolutionary movements inspired the Chicano Liberation Movement. Pancho Villa, Emiliano Zapata and Ricardo Flores Magòn were all heroes to the leaders and activists of the Chicano Movement that emerged in the 1960s and 70s.

The Mexican student movement particularly resonated with young Chicano activists. A student demonstration demanding democracy and protesting the government’s lavish spending for the Mexico City Olympics was brutally suppressed. In the infamous Tlatelolco Massacre of 1968, the corrupt PRI government unleashed their military on the peaceful demonstrators — 300-400 students were slaughtered.

The courage of the Mexican students in the face of this massacre motivated the new young leaders of the Chicano Movement: the Crusade for Justice, the Brown Berets, the Black Berets, Socialists, Communists and the leaders of a vibrant Chicano student movement. These were the radical and revolutionary forces who organized the Chicano Moratorium Against the Vietnam War on August 29, 1970.

That an oppressed community of color organized and led the Moratorium made it a unique phenomenon in the US anti-war movement. The Chicano people possessed centuries-long roots in California and the Southwest, a conquered population when the US annexed Mexico’s northern territories in the 1840s. In 1969 and 1970, twenty moratorium events were organized in Houston, Texas; Albuquerque, New Mexico; Chicago, Illinois; and many California cities.

The largest moratorium event occurred in East Los Angeles, home to the largest Chicano-Mexicano population in the US. More than 25,000 participants protested the US war against the Vietnamese people — and connected that injustice with both the disproportionate casualty rate of Chicano soldiers and the oppression Chicanos suffered in their barrios. One of the main slogans was “Our War Is Not in Vietnam, it is in our Barrios.”

More than 500 police brutally attacked the peaceful protest. They murdered three unarmed Chicanos, including Los Angeles Times journalist Ruben Salazar and two members of the Brown Berets.

Fifty-four years later, the East LA Moratorium continues to be celebrated as a significant historical event in the Chicano struggle for equality and self-determination. The Moratorium demonstrated the movement’s revolutionary leadership, the internationalist political consciousness among the Chicano masses, and the power that comes with unity and organization.

Despite the murderous police assault on their peaceful protest, Chicanos resolutely continued their freedom struggle and their opposition to the Vietnam War — just as the survivors of Tlatelolco continued their fight against authoritarian rule and for social justice. Persecuted by the PRI in 1968 and beyond, those survivors helped lay the foundation for Morena, the progressive party that has twice overwhelmingly won the popular election for governmental power in Mexico.

The Moratorium, like Tlatelolco, is a fire that will never die. We too will prevail. |

|

|

|

|

Recent news reports and commentaries, from progressive and mainstream media, |

|

David Raby, Mexico’s transformation advances with President-Elect Claudia Sheinbaum Labour Outlook. On 1 October Claudia – the first woman to rule this great country of 130 million people, a scientist trained in environmental studies, a model of integrity, progressive principles and democratic commitment – will take office.

Daniela Pastrana, AMLO: gobernar con y para el pueblo Diario Red. El presidente de México, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, empieza su último mes en la vida pública con una aprobación popular de 73 por ciento y una inesperada batalla por la soberanía. Este domingo, en el Zócalo de la Ciudad de México, arengó a mantener la ruta de un gobierno popular que mire por los más desprotegidos.

David Bacon, US Corporations Pump Aquifers Dry in Rural Mexico truthout. Farmers are risking their lives to fight back against the US-owned factory farms that are destroying Mexico’s water.

Carlos Mendoza, El Poder Judicial a las calles Los Reporteros. Dentro de la defensa de los privilegios del poder judicial, sus trabajadoras y trabajadores se encuentran en huelga y han salido a las calles a manifestarse de múltiples formas teniendo interacción con el pueblo.

Cassandra Garrison and Diego Oré, Controversial overhaul of Mexican courts approved by lower house lawmakers Reuters. The democratization of Mexico continues.

Abraham Nuncio, Capitalismo, derecha, chumeles y AMLO La Jornada. Algunas de sus faltas y limitaciones –muy serias en varios casos– tienen que ver con el ejercicio estricto de sus posibilidades, incluso en un país fuertemente influido y en muchos sentidos determinado por el capitalismo imperial de Estados Unidos.

Karen Lellouche Tordjman, Eduardo León, Michael McAdoo, Max Pulido, and François-Xavier Thiebaud, The Shifting Dynamics of Nearshoring in Mexico BCG. An extremely corporate view of the dynamics and “dangers” of Mexico’s recent political, social and economic advance which particularly highlights rising labor power and the assertion of sovereignty as dangers for US imperialism and capital extraction.

María del Pilar Martínez, México registra "avance significativo" en la erradicación del trabajo infantil: USDOL El Economista. Este año, México registró un avance significativo, siendo la evaluación más alta que es posible obtener, y se mide a partir de las acciones que se han implementado en el país.

Alejandra Garcia, AMLO Bids Farewell to the People after Six Years in Power Resumen Latinoamericano. The Mexican President’s political agenda focused on benefiting the most humble. “Democracy is the power of the people….. The opposition wants power without people. To hell with that! We have proven the principle of ‘ First the Poor’.

Leonel Durante, En Chiapas la población civil vive aterrorizada por la violencia AMEXI. Las ONG's exigen la desarticulación de grupos armados en Chiapas para garantizar la vida e integridad física de la población civil. |

|

|

|

|

The Mexico Solidarity Project brings together activists from various socialist and left organizations and individuals committed to worker and global justice. We see the 2018 election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as president of Mexico as a watershed moment. AMLO and his progressive Morena party aim to end generations of corruption, impoverishment, and subservience to US interests. Our Project supports not just Morena, but all Mexicans struggling for basic rights, and opposes US efforts to undermine organizing and Mexico’s national sovereignty.

Editorial committee: Meizhu Lui, Bruce Hobson, Agatha Hinman, Victoria Hamlin, Courtney Childs. To give feedback or get involved yourself, please email us! |

|

Subscribe! Get the Mexico Solidarity Bulletin in your email box every week. |

|

Web page and application support for the Mexico Solidarity Project from NOVA Web Development, a democratically run, worker-owned and operated cooperative focused on developing free software tools for progressive organizations. |