|

|

|

|

The weekly newsletter of the México Solidarity Project |

|

|

|

Online at mexicosolidarityproject.org |

|

November 9, 2022/ This week's issue/ Meizhu Lui, for the editorial team |

|

|

Creator: YinYang, Getty Images |

|

Time for a Tune-Up: Morena Turns Eight |

|

I got a new car in 2014, the same year Morena became a Mexican political party. This new car — my first-ever brand new one — had me thoroughly excited. No scratches, no noises, no problems!

Fast forward eight years. My car has problems. OK, some count as my own fault, like the time I left the car in drive when I exited and the car promptly propelled itself into a ditch. I blame other mishaps on acts of nature, like those mice that ate all the wiring. And don’t get me started on that faulty AC that crashed as soon as the warranty expired.

Morena, meanwhile, began life as a party of a brand-new design, as a civil society organization based in México’s social movements. Andrés Manuel López Obrador led the way. He had left the PRD party, itself a democratic breakaway from the PRI, México’s long-time ruling party. Other left-leaning PRD militants joined Morena when its members voted to register as a political party.

Did this new Morena come with design flaws? Sure did. In an attempt to be as democratic as possible, for instance, the party allowing anyone and everyone to become a member and run for office under the Morena banner. The more popular that banner became, the more opportunists rushed into Morena and ran for office under it.

Did Morena run into problems beyond the party’s control? Most certainly. As always, the United States wants a servant south of the border, not a neighbor. US officials right now are threatening to sue México under existing free trade rules if the Morena government moves to take control of its own energy sector.

Is Morena facing problems caused by its own actions and inactions? Of course, perhaps most notably by failing to maintain and strengthen its social movement base.

But problems always become inevitable as time passes. I’m not ready to junk my eight-year-old car. And within Morena we can see a new fix-it spirit. A younger generation of activists, young people like Alejandro Torres, our interviewee this week, have the technical skills and visionary creativity to do much more than just keep the old buggy running. They’re building a vehicle for real revolutionary change. |

|

|

|

Don’t miss an issue. Subscribe to the weekly México Solidarity Bulletin! |

|

|

|

|

Morena Youth: A Pipeline to the Future |

|

Alejandro Torres, a 23-year-old university student majoring in international affairs at UNAM, has already been a left activist for some eight years. He’s worked to defend public education and gain justice for the disappeared Ayotzinapa students. He’s connected with political and social movements throughout Latin America and now serves as a leader in the Morena party’s Youth Section. |

|

|

Morena has a Youth Section. Who participates and why?

The murder of the Ayotzinapa students in 2014 electrified young people of my generation and turned us from passive dissatisfaction into an activist social force. Students, particularly from the public universities, became determined to stop authoritarianism and the use of violence to silence anyone who disagreed with those who held governing power. |

|

That’s my story. And when the PRI government tried to privatize my school, the Polytechnical Institute, which has mostly working-class students, my outrage became personal.

The new Morena party formed in 2014, and AMLO’s election in 2018 gave young people for the first time in history the space to participate directly in politics, not just in social movements. Morena has a youth secretary who is ensuring that we’re organizing in every state.

The voting age in México currently sits at 18, but you can join Morena at 16. Our Youth Section includes young people from 16 into their 20s. |

|

|

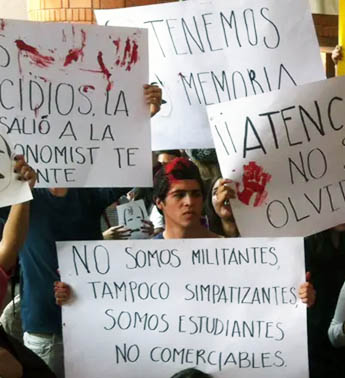

Anti-PRI demonstration in 2012. Photo: Gustavo Sánchez |

|

Students worldwide often stand at the forefront of revolutionary movements. That true in México?

We see the student generation of 1968 as our precursors. Those wanted more democracy and more public services like education. They suffered brutal repression. |

|

No one knows for sure how many students were shot or hunted down back then, probably hundreds. But many others continued to resist and helped form Morena. One example from that generation: author Paco Taibo. AMLO appointed him to head the State Publishing House.

In the 1980s, university students at UNAM in México City once again rose up, and some of those students — like Claudia Sheinbaum, the mayor of México City — are now helping to lead Morena. |

|

|

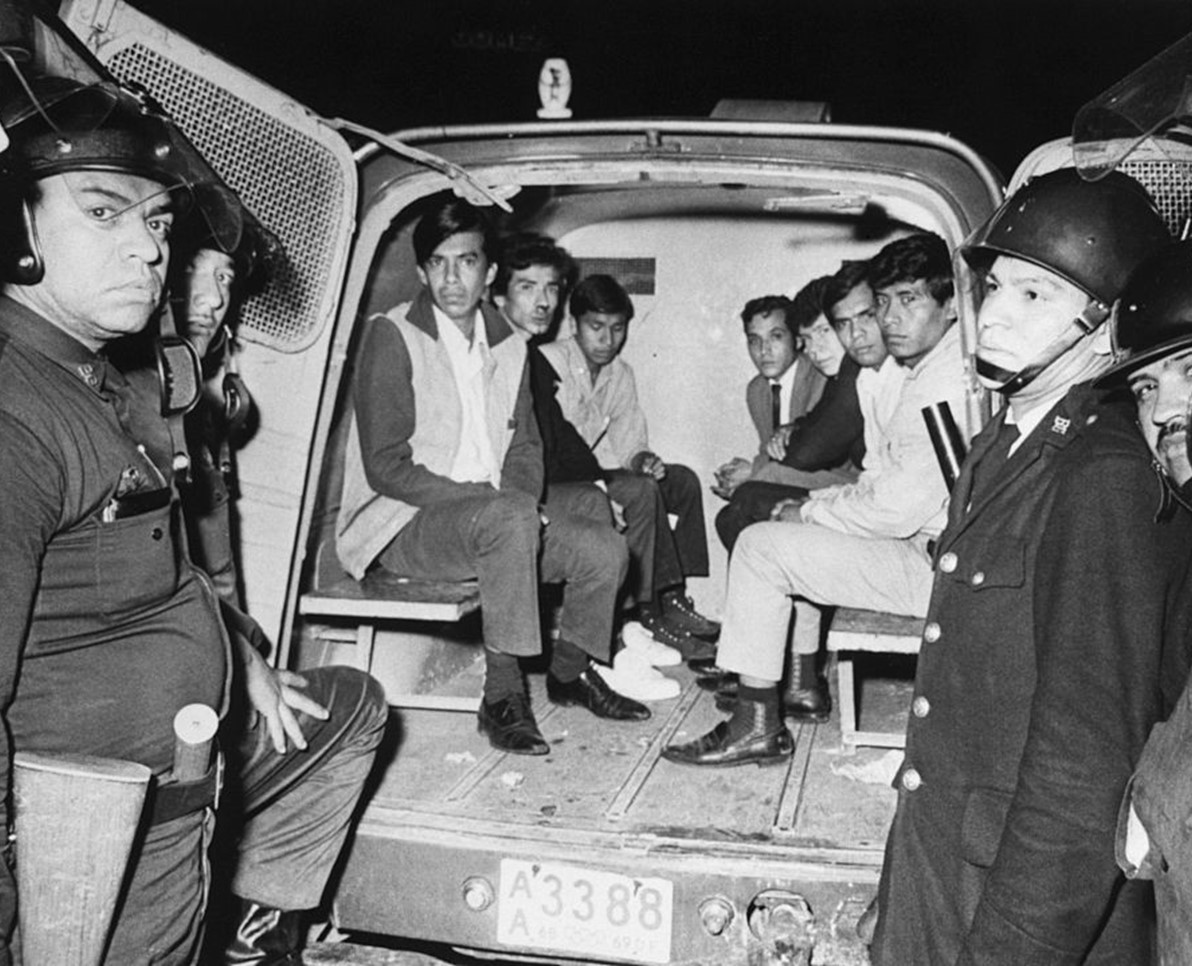

Students in 1968 at Tlatelolcom Plaza. Getty Images. |

|

Then the 2014 student generation denounced Mexican president Peña Nieto for his violent suppression of dissidents and subservience to foreign capitalists. In 2018 we students voted and helped oust the PRI. This third generation of student activists also holds influential positions within Morena. Citlally Hernandez now serves as Morena’s general secretary.

So Morena contains the veterans of several generations of student activists.

Does that give Morena a strong base among young people?

We have a problem today, especially in the cities where neoliberal thinking is influencing many of the young. They’ve become, as we say, “young people with old minds,” more individualistic, less involved in social movements than previous generations. They prefer to work in the private sector. This tendency exists even within Morena, a party that operates as a broad united front.

Right-wing think tanks are consciously attempting to influence students away from Morena’s transformational project, and within the party we have moderates and even neoliberals who do not want to see structural changes in our country. Some have started a big internal debate over the word “leftist.” They want to eliminate this word from our description of who we are! For now, they have been defeated. |

|

What now needs to be done?

We need a new political culture within Morena, to avoid getting contaminated by the political culture of the past. We need to become more self-critical and communicate our break with that culture.

We need to transform ourselves and better embody our principles of service, collectivity, and honesty.

|

|

|

Students protest femicide at Universidad Iberoamericana, |

|

Our challenge as young people: to do all this at the same time, to be more active in traditional spaces, to use the media well, to formulate good policy, and, at the same time, to fight internally within Morena to keep on the right track.

On some issues important to youth, Morena has been both backward and late: the environment, LBGTQ issues, women’s rights. And the party has not focused on the social movements. We will fail if we remain distant from those movements. |

|

Who can best keep Morena on track post-AMLO?

Let’s look at what the two leading candidates for Morena’s nomination to succeed AMLO as president represent. Marcelo Ebrard has a good record on social issues, He fought for gay marriage and abortion rights. But he’s an economic conservative. AMLO, for instance, proposed a new public technical school, but Ebrard made it private. |

|

Claudia Sheinbaum developed her political orientation in the social movements. As a UNAM student, she fought for public education. And as an engineer, she uses a science-driven approach. Her successful public transportation system in México City, for example, integrates metro, buses, and bicycle paths and encourages electric cars.

How do you see your future?

I want to travel so I can hear the people, and to internationalize the fight. We must organize within Morena, and we must organize in the streets. Young people must be patient and persevere. We must fight all our lives to transform reality. With AMLO, hope returned to us. I’m ready. |

|

|

|

On This Day of the Dead: Luis Llopezllera |

|

Our Reflections guest writer this week, Daniel McCool, has a background in development economics and a particular interest in alternative socioeconomic models. He lives in rural Oaxaca, studying new approaches to food production and self-sufficiency. |

|

On the recent morning of Day of the Dead, I was reflecting on those close to me that have passed on when I received an unexpected invitation to a memorial for a widely beloved and respected man. I melancholically added his name to my list.

I first met Luis Lopezllera Méndez, an activist with a huge heart and a miniscule ego, through Multitrueke Mixhiuca, an urban/rural collective he helped found. The Nahuatl word trueque means barter, and the project — dedicated to promoting alternatives to capitalist exchange — began in Mixhiuca, an area of Mexico City. |

|

|

Luis co-founded many organizations over the course of his life, ranging from the Mexican Institute of Social Studies in 1960 and the Authentic Labor Front a year later to the Housing and Population Operational Center in 1962.

But his particular interest always remained in developing alternative democratic economic models that would not profit the few at the expense of the many.

In the early 1970s, Luis served as the first lay president of the Mexican Social Secretariat, a pioneering organization born from the Catholic Church that promoted — from the work at the grassroots parish level — union, cooperative, and popular housing and other social and community economy movements.

Luis also organized the solidarity economy spaces in the World Social Fora in 2008, 2009, and 2010 and promoted 17 “Ecosystemic Dialogues” from 2009 to 2017. His study circles, round tables, and solidarity markets drew national and international participation. Interest today in solidarity economies, thanks in part to his efforts, is rising around the world.

Always a groundbreaker, Luis humbly avoided the limelight and listened attentively. We shall surely deeply miss this éminence gris as our current conjecture of deepening environmental, economic, and political crises continue to unfold.

Luis Lopezllera, ¡presente! |

|

|

Recent news reports and commentaries, from progressive and mainstream media,

Max de Haldevang, México, US Plan Clean-Energy Hub Along Border, AMLO Says, Bloomberg. The two nations are working on ambitious plans to turn parts of the border region into a clean energy hub, replete with solar and wind plants, lithium mining, and electric vehicle factories.

Arturo Sánchez Jiménez, Reprocha Ebrard falta de esfuerzo de EU contra tráfico ilegal de armas, La Jornada. El canciller reprochó este jueves que Estados Unidos no está haciendo un esfuerzo para frenar el tráfico ilegal de armas a México que sea proporcional al que le pide al gobierno mexicano para controlar la introducción a su territorio de fentanilo y precursores químicos.

Daina Beth Solomon, Independent union wins bargaining rights at 3M in central México, Reuters. The dominant CTM labor confederation has now lost a handful of significant factories, following a labor reform and revised trade deal that aim to improve worker rights.

Las economías más poderosas de Latinoamérica brincan a la izquierda por primera vez, SinEmbargo. Los cinco bastiones económicos de América Latina, Brasil, México, Argentina, Chile y Colombia, son ahora controlados por gobiernos de izquierda. Con Brasil la izquierda gobernará al 86 por ciento de población de América Latina.

COP 27-Mexico to make major climate commitment, says John Kerry, Reuters. Mexico, the second-largest emitter in Latin America, last year pledged to expand its climate change goals.

María Fernanda Navarro, Litio, el ‘Oro blanco’, oportunidad para Latam, Indigo. En México en abril de este año el mineral se declaró de utilidad pública la exploración, explotación y aprovechamiento del litio, por lo que no se otorgarán nuevas concesiones a privados para permitir que sea una actividad exclusiva del Estado.

Kiko Martinez, Meet Claudia Sheinbaum, the Front-Runner to Become México’s First Woman President, ReMezcla. Born in México City in 1962, Sheinbaum studied physics at UNAM, where she earned a PhD in energy engineering and physics.

Industria de alimentos chatarra busca revertir etiquetado en México, La Coperacha. Cada hora mueren 27 mexicanos a causa de la obesidad.

Cuba to send México rocks as well as docs, AP. After raising controversy by hiring hundreds of Cuban doctors, México’s president is angering critics again by announcing plans to buy crushed rock ballast from Cuba to complete the 950-mile Maya Train line that will loop around the Yucatan Peninsula, connecting beaches and archaeological sites.

“De un día para otro somos desechables”: la expansión de la vivienda tipo Airbnb en la CDMX expulsa a vecinos de zonas céntricas, Animal Politic. Del 2000 al 2020, el número de viviendas de uso temporal tipo Airbnb pasó de 22 mil 122 a 71 mil 780. Capitalinos cuentan cómo fueron desalojados de sus departamentos por los planes de sus caseros para convertir edificios en más espacios de alojamiento, una situación puede agravarse en los próximos años. |

|

|

The Mexico Solidarity Project brings together activists from various socialist and left organizations and individuals committed to worker and global justice who see the 2018 election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as president of México as a watershed moment. AMLO and his progressive Morena party aim to end generations of corruption, impoverishment, and subservience to US interests. Our Project supports not just Morena, but all Mexicans struggling for basic rights, and opposes US efforts to undermine organizing and México’s national sovereignty.

Editorial committee: Meizhu Lui, Bruce Hobson, Bill Gallegos, Sam Pizzigati, Courtney Childs, Victoria Hamlin, Agatha Hinman, Steven Hollis. To give feedback or get involved yourself, please email us! |

|

|

|

Web page and application support for the México Solidarity Project from NOVA Web Development, a democratically run, worker-owned and operated cooperative focused on developing free software tools for progressive organizations. |