|

|

|

|

The weekly newsletter of the México Solidarity Project |

|

|

|

Every issue archived online at mexicosolidarityproject.org |

|

November 16, 2022/ This week’s issue/ Meizhu Lui, for the editorial team |

|

|

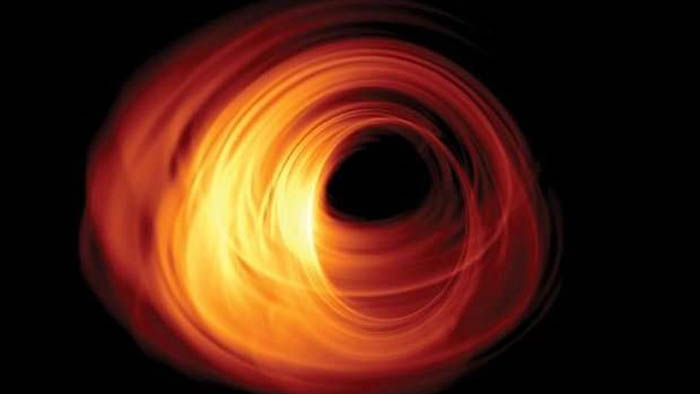

Event Horizon Telescope |

|

Today as Always, the Truth Can Set Us Free |

|

You love someone, and then poof! They disappear. What happened? Why? Where did they go? Your loved one, an extinguished star, has become a black hole in the middle of your being. Today, for thousands of Mexicans, that hole dominates their lives.

Back in the 1970s, over a seven-year period, successive Mexican governments tortured, killed, and disappeared dissidents from a wide variety of backgrounds, from activists in movements of workers, farmers, and teachers to young people radicalized by the 1968 Tlaltelolco massacre of student protesters. We’ll never know the true number of the “disappeared.” A conservative estimate puts the figure at some 1,500.

In all the years since, we’ve seen no justice for the victims of México's brutal guerra sucia, or “dirty war.” But two years ago President Andrés Manuel López Obrador did sign an executive order establishing México’s first truth commission to investigate the government’s crimes. This past June, at a military facility once a main torture center, AMLO unveiled the commission’s members, with family of the disappeared looking on.

Journalist Kurt Hackbarth dives much deeper into this horrific history in his recent interview with the truth commission’s Dr. Carlos A. Pérez Ricart, a professor at México City’s Center for Research and Teaching in Economics. We’ve excerpted from that interview in this week’s Voices.

Disappearances continued long after the 1970s. These crimes also need resolution. Truth, a precious and rare commodity under repressive regimes, remains hard to come by even in more democratic times. But we so need that truth. Those who saw their loved ones “disappear” will always carry the pain of that loss. But the truth can free them — and the rest of us — from the shackles of uncertainty. |

|

|

|

Don’t miss an issue. Subscribe to our weekly México Solidarity Bulletin! |

|

|

|

|

Shining a Light on México’s New Truth Commission |

|

Carlos A. Pérez Ricart teaches international relations at the Center for Research and Teaching in Economics in México City. An expert on the influence of the US government on México, he’s devoted particular attention to how US drug enforcement agencies have impacted the design, implementation, and evaluation of Mexican drug policy. Pérez Ricart is currently serving as a member of México’s new truth commission, and he spoke recently about that panel’s work with journalist Kurt Hackbarth in an interview for the Jacobin. We’ve highlighted key portions of that interview here. |

|

|

The dirty war, in your words, was “extended, premeditated and cruel.” But in comparison with other Latin American countries, very little of this has been discussed in México. Why?

The dirty war, a global phenomenon, has to be understood in the context of the Cold War. In Argentina, where they had a savage dictatorship and a large number of disappeared, a broad educational project took place in the wake of its dirty war. A figure like Jair Bolsonaro would be unthinkable in today’s Argentina. |

|

Even in the context of a terrible economic crisis, nobody is even considering the possibility of a military regime returning to power because of the educational process that occurred.

That construction of truth, with the victims at the center, has been missing in México.

Critics of AMLO see the new Mexican truth commission as little more than a simulation designed to shelve the whole issue of the dirty war. |

|

|

Banner at 2022 anniversary protest of the Tlatelolco massacre. Photo: Claudio Crux/AFP via Getty Images |

|

The dirty war wasn’t sitting on anyone’s agenda, not even on the president’s agenda, until four years ago. The truth commission we have now exists thanks to pressure from the organized victims’ groups and assemblies. The idea, the project, the negotiation, the force came from the victims, and anyone who’s familiar with this process would consider it absurd to suggest, as some have, that this project aims to rehabilitate the military.

I see this as the beginning of a broader process, a ladder to allow us to build the foundations for a new culture of human rights. By that I mean rights for everyone, from the poor to the LGBTQ community and all of those who have been seen as “other.”

The essential idea: to expand the concept of rights to people who don’t even know that their rights have been violated, who saw what happened to them as a normal part of life. We can tell them that if you were displaced or assaulted due to your religious orientation or for speaking another language or just because you were poor, you have rights. You can organize, you can demand reparations. The right to truth and justice exists for you too, and not only for the circle of victims active on the Left and well aware of their rights.

Just to mention one case: the 1972 operation in the town of El Quemado in Guerrero. The army came in, tortured eighty men, and took them prisoner. But what happened to the women? They were raped, they were forced to marry, in some cases forced to have children and in others to take birth control pills.

The women have also been victims, but until now they’ve been erased. What happened to them? What happened to their children? Here we are broadening the concept of victim, not only focusing on what is obvious but ensuring that our narrative includes the wives, the mothers, the daughters, the sons.

Your investigations may reveal that the United States played a larger role in the dirty war than previously known. Do you have any concern that the commission’s revelations could affect bilateral relations?

What happens happens, and we’ll say what has to be said. The dirty war connected transnational networks of repression. This is what Operation Condor has taught us. We don’t yet have a clear picture, and that’s why our project will include a search of US archives using the Freedom of Information Act. |

|

We’ve met with Kate Doyle, a senior analyst at the National Security Archive and an expert in US policy in Latin America. She’s part of an advisory group to the commission and will be helping us access the archives of the CIA, the FBI, and over agencies.

You have written about the importance for the commission to create a “politics of memory.” What do you mean?

We believe that the criminal and authoritarian circuits that have enabled the violence of the present were built in the period of the 1970s and 1980s. |

|

|

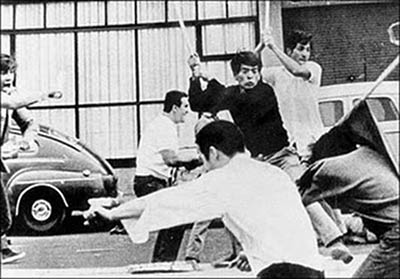

President Echeverria’s paramilitary forces, probably |

|

This period saw the founding the Mexican state’s authoritarian enclaves, and that’s why we believe that the violence and impunity of the past made possible the violence, impunity, and criminal networks of the present. |

|

The politics of memory has to speak to the present while obliging us to look at the past — to see it, resolve it, and be able to move forward. The wounds have been covered over but remain infected and have to be closed. We have to look with one eye to the past to be able to advance with the other eye toward the present. That past created the México of today. |

|

|

Parents of disappeared Ayotzinapa students. Photo: Christian Palma/AP |

|

|

|

Share this interview. Just forward this México Solidarity Bulletin issue to a friend! |

|

|

|

|

|

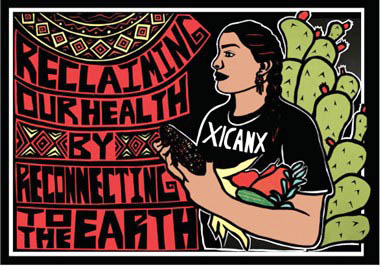

California’s Art Workshop of the New Dawn |

|

José A. Arenas directs the Taller Arte del Nuevo Amanecer, the Art Workshop of the New Dawn. Arenas, who also teaches the Chicana/o Mural Workshop in the UC Davis Department of Chicana/o Studies, talked to me about the place of TANA in the Woodland community and the University of California at Davis. His perspective follows. |

|

It just feels so good to see young people use the Taller for expressing their ideas and as agents of change. Elyse Doyle-Martinez from UC Davis and her team, for instance, collaborated with Brown Issues, a Woodland organization for young people, to create a show around safety in Woodland, a community 49 percent Chicano. Young people are dealing simultaneously with not feeling safe and being over-policed, both real and tangible issues for them. |

|

|

We’re cementing relationships with the Woodland Joint Unified School District’s principals and teachers.

Last year, a group of 18 students in the mural class connected with Plainfield Elementary and engaged students in conversation about, among other things, the rich agricultural heritage that Woodland has, including immigrant labor. |

|

|

A lot of parents work at the Cannery, a block away, or do farm work. People know that they can not only come to TANA to be creative, but to use it as a community space where organizing can happen.

We go to classrooms, but by offering cultural events, exhibitions, and more, we’re also bringing classrooms into TANA! |

|

|

In our new garden here, we're already doing some programming related to food justice. We’re thinking about how growing food relates to indigenous practices, like the “Three Sisters” of corn, beans, and squash that provide all the nutrition we need. |

|

We have an opportunity to provide an educational context that relates to our indigenous roots. Now, some twelve years in, we’re really reinforcing community involvement.

TANA continues to grow in so many ways! |

|

|

Activist Vicky Hamlin, a retired tradeswoman, |

|

|

|

Recent news reports and commentaries, from progressive and mainstream media, on life and struggles on both sides of the US-México border |

|

Aleida Rueda, Latin America, the US’s new plastic dumping ground, Pressenza. Every year the US sends thousands of tons of plastic waste into México.

Derechistas radicales (racistas, corruptos, nietos de dictadores…) se reúnen en CdMx, Sin Embargo. La reunión de la Conferencia Política de Acción Conservadora en la capital mexicana traerá a múltiples políticos, activistas y seguidores de extrema derecha de diferentes partes del mundo.

Rich Tenorio, A forgotten revolutionary leader’s new relevance in AMLO’s México, México News Daily. Morena’s National Development Plan, the party's move to transform the country during AMLO’s term, cites Flores Magón and his historic 1906 revolutionary manifesto as its inspiration.

'Veo un México boyante... Las finanzas públicas estarán sanas hasta el fin de este gobierno': Carlos Slim, Aristegui. Slim dijo que México debe ser capaz de generar los empleos que los mexicanos están yendo a buscar a Estados Unidos.

Carlos Rosado van der Gracht, Could this be México’s first female president? Yucatan Magazine. A handful of Mexican women have run for president, but none have registered over 3 percent of the vote.

Mujer reclama a AMLO en pleno vuelo; pasajeros apoyan al presidente con aplausos, Indigo. Se trata de una grabación en la que una pasajera que viajaba en el vuelo comercial Ciudad de México-Mérida, en el que se encontraba el AMLO.

Mexican president says government cannot buy genetically modified corn, Financial Post. A Mexican presidential decree seeks to ban genetically modified corn in 2024 and phase out the herbicide glyphosate found in Roundup.

Luis Negrete, Guanajuato rechaza permanencia del Ejército en las calles hasta 2028, Excelsior. La mayoría panista y sus aliados en el Congreso de Guanajuato rechazaron la permanencia de las fuerzas armadas en funciones de seguridad pública.

México president eyes giving presidential jet to planned military-run airline, Reuters. AMLO is proposing to hand over the opulent presidential plane he inherited from his predecessors to a new military-run airline that would rent the plane to workers.

David Shortell and Lorena Ríos, How Droughts in México Could Shape the Future of the Beer Industry, New York Times. With droughts becoming more frequent and severe, an activist movement to reclaim resources from corporations has gained recognition at the highest levels of the Mexican government. |

|

|

The México Solidarity Project brings together activists from various socialist and left organizations and individuals committed to worker and global justice who see the 2018 election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as president of México as a watershed moment. AMLO and his progressive Morena party aim to end generations of corruption, impoverishment, and subservience to US interests. Our Project supports not just Morena, but all Mexicans struggling for basic rights, and opposes US efforts to undermine organizing and México’s national sovereignty.

Editorial committee: Meizhu Lui, Bruce Hobson, Bill Gallegos, Sam Pizzigati, Courtney Childs, Victoria Hamlin, Agatha Hinman, Steven Hollis. To give feedback or get involved yourself, please email us! |

|

|

|

Subscribe! Get the México Solidarity Bulletin in your email box every week. |

|

|

|

Web page and application support for the México Solidarity Project from NOVA Web Development, a democratically run, worker-owned and operated cooperative focused on developing free software tools for progressive organizations. |