|

|

|

|

The weekly newsletter of the México Solidarity Project |

|

|

|

Online at mexicosolidarityproject.org |

|

May 31, 2023/ This week's issue/ Meizhu Lui, for the editorial team |

|

|

Guestworker Programs: ‘No Way to Treat A Guest’ |

|

After World War II, Germany brought in workers from Turkey, on a temporary basis, to help the country rebuild. Germans called these workers Gastarbeiter —guest workers — and US officials would later adopt that phrasing. Germany’s program would prove a success and get considerable credit for the nation’s postwar economic comeback miracle.

But legally contracted "guest workers” actually go much farther back in US history than WWII, as historian Maria Quintana explains in our interview this week. These workers, like their counterparts in Germany, have always provided a great service to their host countries. They’re filling a desperate need for labor. If they weren’t, they wouldn’t have been “invited” in the first place.

The value that US guest workers provide has never translated into placing value on these workers. The recruiters in México that US growers hire to recruit these workers, eyewitness reports relate, at times behave like modern-day slavers. Just like their predecessors who closely examined African bodies, these recruiters care about nothing more than the capacity to do back-breaking work. They ask potential “guests” to show them their hands. Rough and calloused hands signal that the recruiters have found an ideal candidate.

And that, as advocates at Farmworker Justice note, makes for no way to treat a guest. Our current “guest worker” statutes paper over abuse and give “legal" status to harsh contract inequalities. Maria Quintana’s research can help all of us shift our focus and see guest “legalization” by way of contract as part of the problem. How about instead honoring the humanity of all workers, whether US- or foreign-born, temporary or permanent? |

|

|

|

Don’t miss an issue! Sign up for a free México Solidarity Bulletin subscription. |

|

|

|

|

The ‘Legalization’ Frame Hurts All Migrant Workers |

|

Maria Quintana, a Sacramento State University historian, teaches courses that cover topics ranging from race, empire, and civil rights to labor, immigration, and Latinx history. She’s also taught at San Francisco State University’s College of Ethnic Studies. For a special discount on her recently published book, Contracting Freedom: Race, Empire, and U.S. Guestworker Programs, check online and use the code QUINTANA30.

Do you have a personal connection to the story of “guest workers” in the United States? |

|

|

My great uncle worked as a bracero, and I grew up in a neighborhood called “la colonia," a former orange orchard that hired braceros. I always wanted to know more about the colonial roots of the Bracero Program, and my family’s history as the working backbone of California also interested me.

How did the idea of temporary work — based in a labor contract between individual worker and employer — take hold in the US?

This idea originated in England. With slavery about to be ended in the early 1800s, slave owners in the British West Indies wondered who was going to be doing the work once they had no slaves. How could they get docile workers that they could control?

Their answer — a system that described workers “free” with contractual rights and paychecks — offered a solution that skirted the arguments against slavery. Plantation owners started to import workers from India to the British West Indies on this basis.

In the United States, with the mass importation of Chinese after slavery’s abolition, some protested that “coolie labor” amounted to “slave labor.” This sentiment led to the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Acts, as well as the 1885 Foran Act, legislation that prohibited imported foreign labor.

But the Foran Act had a loophole that allowed Mexican workers with temporary contracts into the United States, and employers used this loophole in 1917, before US entry into World War I. But the program proved short-lived. The Mexican government ended it in 1921, in part due to the exploitation of workers that the loophole made possible. |

|

At that time, with little border enforcement, travel between the US and México for seasonal work remained pretty fluid. But contracted labor became popular again after the 1930s as the success of the New Deal changed the concept of the state. People began to see the government as a benevolent force that could protect workers.

By 1942, a new consensus had emerged, shared by conservatives and liberals. They agreed that importing foreign workers who could freely enter into legal contracts determining the terms of their employment would bring mutual benefits to both worker and employer. |

|

|

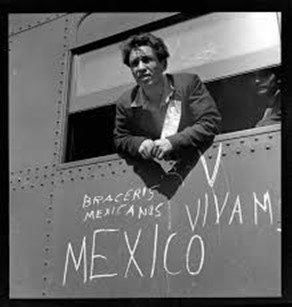

Photo: Dorothea Lange, 1942 |

|

Unions as well as employers supported this idea of contract labor. Legendary farm worker organizer Ernesto Galarza, for instance, felt that a labor arrangement modeled on Depression-era resettlement programs — efforts that provided internal US Dust Bowl migrants with housing and new skills — could benefit Mexicans as well. These workers could learn new skills and take those skills back to México. So the Bracero Program originally faced little opposition.

The Bracero Program emphasized the worker freedom to accept a contract. Why do you say that guest worker programs actually served to legitimize US imperialism?

Contracts for temporary labor coerce. They tie a worker to a single employer, with no supervision of the contract to guarantee a basic standard of living.

Labor contracts also expand state power over immigrant workers. In effect, the “legality” of these contracts produces the problem of “illegality.” You cannot be “illegal” without a “legal status” for comparison. The US Border Patrol in 1924 began as a program too small to be effective. But after 1942 — and the start of the Bracero Program — the Border Patrol’s numbers increased twenty-fold!

Also in 1942, after Pearl Harbor, the government put the Japanese in the US, many of them agricultural workers, into concentration camps. Officials essentially co-constituted Japanese internment and the Bracero programs, after multiple hearings that considered both populations and how to treat them. Living conditions for both became similar.

An “empire” has complete state control over its population. In the United States, workers categorized as “foreign” became subject to US imperial rule. Workers did resist, with work stoppages and ripping up and breaking contracts by leaving their contractual employer. But their moves to escape their contracts broke the law. “Legality” increased oppression. |

|

Did the growing civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s impact the braceros?

Ernesto Galarza, appalled at the actuality of the Bracero Program, spent the rest of his life fighting bracero mistreatment. The National Farm Labor Union — the NFLU — that Galarza led tried to organize braceros with domestic farmworkers, but the growers could just fire “troublemakers” and replace them with either contract or undocumented workers. |

|

|

Photo: AFL-CIO |

|

Immigrant workers came to be seen as a problem, a group that undercut efforts to organize and protect domestic/citizen workers. Even among union organizers, the division became not just a conflict between workers and bosses, but also between domestic and migrant labor. The question in my research became, “Civil rights for whom?” The struggle for civil rights left out guest workers.

How and why did the bracero program end, and what has happened since then?

The United Farmworkers finally brought national attention to the reality of the conditions braceros labored under, and the 1960 network television documentary Harvest of Shame reached a wide audience. The Bracero Program ended in 1964, with, once again, the debate around that move stressing the need to protect domestic workers.

In 1986, to deal with the problem of predominantly Mexican undocumented workers, the Immigration Reform and Control Act — the IRCA — became law. This legislation traded off granting some immigrants a path to citizenship with making other immigrants even more vulnerable to deportation. Since then, with the continued liberal consensus on the issue as “legalization,” that trade-off has been part of every major immigration reform proposal.

The new H2-A rules on the “Temporary Agricultural Employment of Foreign Workers” allow more workers to come into the US with individual contracts that tie them irrevocably to individual growers and make them vulnerable to corrupt recruiters in México.

These rules subject agricultural laborers without papers to the growing militarization of immigration control. We’ll see deportations — already at all-time highs — increase even more, since legalization requires an expansion of state power to enforce the law. Contract labor remains bad for both new guest workers and undocumented laborers already working. |

|

What can we do?

We must defend all farmworkers. Our agricultural industry depends on them.

We must demand the same borderless world that corporations and capital live in. We must demand that worker rights be the same for all workers, citizens and migrants alike.

For those of us who oppose colonialism and imperialism, we must recognize that contract labor perpetuates those systems of oppression. |

|

|

A Still Revealing Look at the Border’s Strains |

|

Al Otro Lado (To the Other Side), a film by Natalia Almada, 2005. |

|

Natalia Almada made this film nearly two decades ago, in 2005. Some things have changed since then, especially with the anti-corruption campaigns AMLO and Morena have waged and the changes the AMLO years have made in the lives of working and poor people. But border issues most certainly remain, and Almada develops this fine film’s overarching theme through the story of Magdiel, an aspiring 23-year-old corrido singer. |

|

|

Magdiel is bursting at the seams to gain an audience and make money, without having to work for the drug cartels. He believes he can make all this happen if he can just cross onto the border’s “other side.”

On-the-ground reality, filmmaker Almada shows, complicates all that. People can rarely see past their immediate needs or envision a future outside of their direct experience. Poverty does unimaginable things to people who have no access to money, jobs, and choices. |

|

We’ve seen in the United States a recent and understandable pushback against the glorification of cartel life in the narcocorridos. The stories Almada tells play out raw. She’s done a masterful job interweaving visual, musical, and visceral elements into a story with no end. |

|

|

Alamada’s editing takes us right along with her into the strains and binds that make people faced with impossible dilemmas feel like they’re going to explode. |

|

In the course of this documentary, Almada talks with corrido singers and musicians, border crossers, and coyotes. She introduces us to real — and self-appointed — border patrol agents, documented and undocumented immigrants on both sides of the border, young people, old people, and everyone in between. |

|

|

Al Otro Lado shares honest talk about the cartels and the roles they play in Sinaloa, a community with few options. Almada journeys with people as they try to cross to the “other side,” as they live their daily lives, as they try to support their families and live with dignity, joy, and growth. |

|

Almada’s film never gets sentimental or academic. She has a gift for understanding and displaying complexity.

Times change, but the immigration story remains with us, told ever so well in this universal tale of Everyman. |

|

|

Activist Vicky Hamlin, a retired tradeswoman, shop steward, and painter, shines the light — in her art and this column — on the lives of working people and the world they live in. |

|

|

|

Recent news reports and commentaries, from progressive and mainstream media,

Juan Pablo Spinetto, AMLO’s Latest Move Unnerves México’s Business Elite, Bloomberg. The Mexican government has seized a portion of a railroad belonging to billionaire Germán Larrea in a move to help create a transportation hub in the isthmus of Tehuantepec that separates the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific Ocean. Authorities hope the development could one day rival the Panama Canal.

Ya son 5 los jóvenes desaparecidos en Zapopan, Sin Embargo. En total, se estima que en el país hay más de 112 mil personas reportadas como desaparecidas, y sus familiares a menudo tienen que buscarlas debido a la falta de acción por parte de la policía.

Andrea Navarro, AMLO Says México Could Offer $3 Billion For a Stake in Banamex, Yahoo Finance. Citigroup’s Banamex “could represent a good opportunity” for Mexico to own a bank, President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador last week noted.

Calderón desvió $2 mil millones de Salud para medios de comunicación, Contra Línea. El gobierno de Felipe Calderón Hinojosa desvió más de 1 mil 998 millones de pesos del presupuesto de la Secretaría de Salud (Ssa) para el pago a medios de comunicación y de consultorías.

Mexican president urges Latino voters to reject DeSantis after campaign launch, Reuters. DeSantis, has championed border security and derided so-called "sanctuary cities" where migrants can shelter.

Pedro Rendón, Pedagogías radicales subsanan rezago educativo y falta de oportunidades, des Informémonos. Pedagogías radicales subsanan rezago educativo y falta de oportunidades.

Rafael Bernal, López Obrador doubles down: ‘Fentanyl is not produced in México,’ The Hill. López Obrador’s pushback against a seemingly semantic distinction has political undertones. In response to a question last week, the Mexican president criticized his predecessors for taking orders from US government agencies.

Lilian Hernández Osorio, Sección 22 alista paro tras fracasar diálogo con la SEP, La Jornada. La dirigencia del magisterio de la sección 22 de Oaxaca denunció que los gobiernos federal y estatal no atendieron las demandas en la mesa que sostuvieron en la semana pasada, pues no hubo disposición ni "capacidad política" para el diálogo.

México in Numbers: Political Parties, México News Daily. A primer on México’s political party line-up and upcoming elections. Mexico has seven recognized national political parties.

Pedagogías radicales subsanan rezago educativo y falta de oportunidades, Ibero. Las pedagogías radicales --que encuentran su lugar en la frontera entre la comunidad y la escuela-- potencializan la colaboración interdisciplinaria y subrayan la importancia de que docentes y estudiantes reflexionen en torno a sus propias experiencias familiares, emocionales y comunitarias, así como el trabajo de base. |

|

|

The Mexico Solidarity Project brings together activists from various socialist and left organizations and individuals committed to worker and global justice who see the 2018 election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as president of México as a watershed moment. AMLO and his progressive Morena party aim to end generations of corruption, impoverishment, and subservience to US interests. Our Project supports not just Morena, but all Mexicans struggling for basic rights, and opposes US efforts to undermine organizing and México’s national sovereignty.

Editorial committee: Meizhu Lui, Bruce Hobson, Bill Gallegos, Sam Pizzigati, Courtney Childs, Victoria Hamlin, Agatha Hinman, Steven Hollis, Daniel McCool, Betty Forrester, Jesús Hermosillo. To give feedback or get involved yourself, please email us! |

|

|

|

Subscribe! Get the México Solidarity Bulletin in your email box every week. |

|

|

|

Web page and application support for the México Solidarity Project from NOVA Web Development, a democratically run, worker-owned and operated cooperative focused on developing free software tools for progressive organizations. |