|

|

|

|

The weekly newsletter of the México Solidarity Project |

|

|

|

Online at mexicosolidarityproject.org |

|

December 14, 2022/ This week's issue/ Meizhu Lui, for the editorial team |

|

|

Kate Winslet as Ronal in Avatar: The Way of Water |

|

The Creation of a New People: Chican@s in the US |

|

Many of us cheered in the movie Avatar for the endangered blue Na’vi on Pandora as they faced getting sacrificed on the altar of human “civilization.” Their story resonated with us. We’ve heard about real peoples who’ve gone extinct when big ranchers have chopped down the forests they depend on or forced them to stop speaking their own language.

But few of us have ever heard about the creation of peoples, a creation that’s happened right here in the USA. Our interview this week spotlights native Coloradan Bill Gallegos, one of the activists back in the 1960s who first recognized that he actually belonged to a new national formation — a new people — that had developed in the US Southwest.

Gallegos and other activists named this population Chicanos and the land they inhabited Aztlán, the territory the United States annexed from México.

In 1848, people of Spanish/indigenous heritage who had been living in this same territory for generations suddenly found themselves no longer living in México. They were living in the USA, treated like a conquered people, subordinated to whites. Many of them lost touch with family on the other side of the border. Many lost most of their language, since they now lived in an English-only nation. But they never became “American” either. They lived segregated into poorer neighborhoods, schools, and jobs, separate and unequal.

Resistance meant fighting to hold onto their Spanish language and retaining Mexican foods, music, and celebrations. Resistance meant developing their own local economies. But mostly resistance meant fighting for their land, resisting poisonous incursions into their environment, using all means necessary to win equality under the law. Not allowed to be either Mexican or American, they became an identifiable people in their own right.

Chican@s still struggle for control of their own destiny. Just as we cheered for the blue Na’vi in Avatar, let’s cheer for our own brown Chican@s! |

|

|

|

We’ll be taking our annual end-of-the-year break over the next two weeks. Have a wonderful holiday season and see you in the new year! |

|

|

|

Don’t miss an issue. Subscribe to the weekly México Solidarity Bulletin! |

|

|

|

|

The Chican@ People: Born in the USA — in 1848 |

|

Bill Gallegos, a longtime Chicano revolutionary who lives in Los Angeles, has been active over the years with groups ranging from the Crusade for Justice and the Brown Berets to the Partido La Raza Unida and the August 29th Movement. He’s currently organizing with Liberation Road and the México Solidarity Project. His authored analyses include The Struggle for Chicano Liberation and The Sunbelt Strategy and Chicano Liberation.

You identify as Chicano. What do you see as the difference between Chican@ and Mexican@ or Mexican-American? |

|

|

Bill Gallegos, in the Chicano movement’s early days |

|

My people lived in Colorado for generations before I grew up there. Chican@ is Mexican-American. We’ve lived in the same territory for centuries, in that part of México annexed by the US in 1848. We became a conquered people. But separated from our homeland, we could neither develop as Mexicans nor become US citizens equal to whites. We became something new.

In the 1960s, during the Civil Rights upsurge, we took the name “Chicano” to assert our unique character and affirm our roots. Mexicans who migrate to the US can’t assimilate like European immigrants. They end up where they’re comfortable and where racism compels them to reside: in Chican@ communities. By the second generation, they have become Chican@s too.

How did the US come to take Mexican territory?

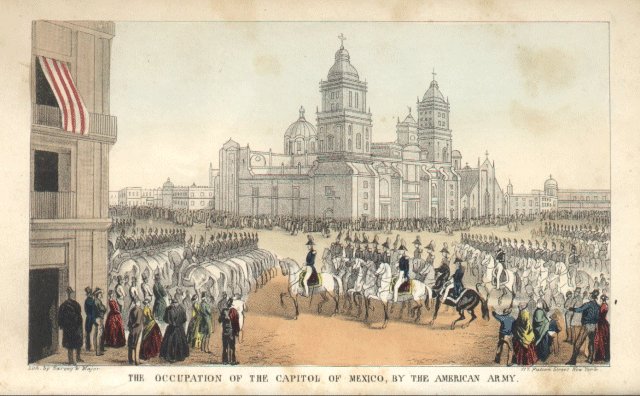

The prime motivation came from the Southern states. They wanted new areas where they could spread slavery. They pressed for war. México had outlawed the slave trade throughout the entire Mexican nation, including Texas, soon after winning independence in 1821. In 1846, the US president accused Mexican troops of attacking “Americans” on US soil. He sent in troops. They outgunned and defeated México in 1848. |

|

|

What impact did the US takeover of the Southwest have on the United States and its subsequent development?

White settlers streamed into the new territories and claimed the land for themselves, stealing millions of acres outright or through US land courts that operated only in English. The United States won control of vast tracts of fertile land for agriculture and ranching, as well as huge deposits of oil, coal and gas, and gold and silver. |

|

The US subsequently built up both national rail and coastal port networks to facilitate trade with Pacific rim countries. The annexed Mexican land “made America great,” enabling the United States to leapfrog over England, Germany, and other imperial powers to become the world’s number one superpower.

What impact did all this have on México? |

|

To the winner go the spoils, and to the loser? Immiseration. The loss of territory sealed México’s fate as a neocolonial nation, with US companies allowed not just to enjoy the riches of the new US territories, but to go into México itself and fatten themselves on the abundant natural and human resources they found there.

To enforce that unequal relationship, the US has invaded México at least ten times since 1848. In 1914, for example, a tiny incident of miscommunication between US sailors and the Mexican authorities in Veracruz provided the US with an excuse to invade. Washington “sent in the Marines” — and a massacre of Mexican civilians ensued.

But the United States would rely mainly on bribery and investment to get what it wanted, establishing a cozy relationship with the PRI — México’s ruling party for 70 years — that opened the doors to US corporations. |

|

And the impact on Mexicans living in those territories added to the US?

In 1848, at the end of the war, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo gave Mexicans the right to maintain ownership of their land and the right to a free education, in the language of their choice! But just like with the treaties the US signed with Indian Nations, the US never honored this one.

Instead, the dispossessed Mexicans became the backs and hands of the new owners, working in the mines, building the railroads, and doing the stoop labor — all at the special “Mexican rate.” In some places like Texas, the powers that be enforced these conditions with brutality, bribery, and political manipulation. Amid this conquest, oppression, and resistance, the Chicano people took shape.

Have Chican@s played an important role in supporting the Mexican people?

Mexicans in the US have returned to México to fight in México’s revolutions. People like Ricardo Flores Magon played leading roles a century ago. In more recent times, Chicanos organized caravans of support for the Zapatistas after their uprising in 1994. They brought food, clothes, and other necessities — and raised enough public concern in the United States to make it more difficult for the Mexican government to just go in and massacre the Zapatistas. And when AMLO was elected and Morena took control of Congress, Morena chapters sprang up in the US to add their support.

Have Chican@s impacted progressive changes in the United States?

Lots. Chican@s helped enslaved people escape to México on the “southbound underground railroad.” We organized mineworkers into unions in the Southwest. I had family in Colorado present at the infamous Ludlow Massacre in 1914. In 1947, we won an end to segregated schooling for Mexican American and white students, seven years before Brown vs Board of Education ruled segregation in the South unconstitutional. |

|

Together with Filipino organizers, we won the first union rights for farm workers. Full civil and human rights for immigrants? We’ve been the leading edge. And our insistence on voting rights — and our votes themselves — have expanded US democracy.

Chicanos have also made a huge contribution to the US left and the fight for socialism by building the August 29th Movement (M-L) and developing the theory of Chicanos as an oppressed nation. Our history shows that liberation starts with self-determination. |

|

|

Mexican@/Chican@ Resistance Across Borders |

|

|

|

Pedro Castillo visiting the Amazon region after an earthquake. Photo: Twitter/Pedro Castillo |

|

The Latin American Right’s Undemocratic Core |

|

The Latin American right has once again shown its true face.

After months of efforts by the obstructionist Peruvian Congress to impede the ability of the democratically elected President Pedro Castillo to govern, the country’s right-wing parliamentarians have unceremoniously booted Castillo from office. |

|

Castillo’s ouster came days after an Argentine court sentenced that nation’s vice president, Cristina Fernández, to six years in prison and ordered her political disqualification from office for life, a triumph for a “lawfare” campaign aimed at neutralizing popular political candidates just like her. |

|

|

What do these two episodes tell us? The right in Latin America will resort to anything to stop the left. And here in México the political opposition to Morena is practically salivating at the notion that it could pull off something similar.

In Peru, the election of Castillo, a rural teacher, had shocked the political establishment. A man who grew up tending livestock sitting on the presidential throne! The right could not tolerate that. Right-wing forces led by Keiko Fujimori, the daughter of former Peruvian dictator Alberto Fujimori, engaged in a relentless destabilization campaign to keep Castillo from implementing the progressive agenda he was elected on.

“His adversaries,” as Mexican President López Obrador noted at a news conference last week, “did not accept that he would govern.”

Castillo, a political neophyte, struggled to navigate this assault. He went through five cabinets and two failed impeachment attempts. Desperate for some measure of stability, Castillo pivoted to the right, even inviting the Organization of American States to help. But that would not satisfy his opponents.

Finally, exhausted and at wit’s end, Castillo announced last Wednesday the dissolution of Congress and the installation of an “exceptional emergency government” that would rule by decree. He further called for the election of a constituent congress to draft a new constitution for Peru, a longtime demand by popular movements that sought to replace the 1993 Constitution implemented during the Fujimori dictatorship.

But that maneuver backfired after the country’s political class, as well as the armed forces and national police, announced they would not support the move. They labeled Castillo’s dissolution a “self coup,” with the US Embassy in Peru calling it “extra constitutional.” Peru’s Congress, already set to vote on a third impeachment effort that same day, quickly approved Castillo’s ouster.

The Peruvian people did not let this move go unanswered. Protests broke out in various parts of the country, and the General Confederation of Workers of Peru has called for a nationwide strike. But with Castillo detained in a high-security jail, his return to office appears unlikely.

The deeply unpopular Congress may have won the day, but the ouster of a democratically elected president may ultimately prove to be a pyrrhic victory. The problems that led Peruvian workers and campesinos to elect Castillo remain — and so will the country’s political instability.

Latin America’s political and economic elites continue to believe they hold the birthright to rule. But in a democracy, Latin America’s masses will forever remind them, that right remains theirs. |

|

José Luis Granados Ceja, a Mexican freelance journalist, is currently studying human rights and popular democracy at the Autonomous |

|

|

|

Recent news reports and commentaries, from progressive and mainstream media,

Debbie Slobe, Why are more families immigrating to México? México News Daily. More than 1.2 million foreigners live in Mexico — nearly 300,000 over a decade ago.

AMLO urge a conservadores a ya definir quién será su candidato (a) a la Presidencia, Arestegui. La elección presidencial del 2024 "va a ser como un referéndum, una consulta", aseguró el presidente López Obrador.

Kendal Blust, Watered-down electoral reforms advance in México, Fronteras. The new plan would make it easier for Mexicans abroad to vote online.

CDMX es ahora más segura que algunas ciudades de EE.UU: Latinometrics, Indigo. Asimismo, la publicación señala una de las principales consecuencias de la llegada de cada vez más personas extranjeras a la CDMX: la gentrificación.

Camilo Montoya-Galvez, Biden administration to appeal ruling invalidating Title 42 border restriction, but won't seek to delay its end, CBS News. The Biden administration will be appealing a court ruling that invalidated a public health order U.S. border officials have used to expel migrants en masse from the U.S.-Mexico border.

Gobierno de Perú reclama a AMLO y a Ebrard expresiones sobre asilo político a Pedro Castillo, Animal Político. El gobierno de Perú, ahora encabezado por Dina Boluarte, cuestionó expresiones del presidente Andrés Manuel López Obrador y del canciller Marcelo Ebrard sobre un posible asilo político a Pedro Castillo, quien fue recientemente destituido y detenido en aquel país.

Bill Tomson, US corn growers say no to México’s GMO deal, AgriPulse. Mexican President López Obrador says the US should understand his desire to ban imports of GM food-grade corn, but American farm groups are firmly rejecting the idea.

Bernardo Barranco V., Eduardo Verástegui, punta de lanza de la ultraderecha en México, Proceso. El cónclave de la ultraderecha internacional realizado en México los pasados 18 y 19 de noviembre fue organizado por la Conferencia Política de Acción Conservadora. Ahí se anunció que tienen planes de crear un partido de “derecha verdadera en México”, pues Acción Nacional, dijeron, no representa la agenda de un verdadero partido conservador.

President Lopez Obrador calls for respect for human rights in Peru, Prensa Latina. “Non-intervention and self-determination” remain “a pivotal principle of our foreign policy,” AMLO noted, but “we consider it as regrettable” that Peru’s economic elites have maintained “an atmosphere of confrontation and hostility” since the beginning of Pedro Castillo’s presidency.

Blanche Petrich, Víctimas de la guerra sucia dan "el último jalón" contra la impunidad, La Jornada. Han pasado las décadas y los sexenios y los perpetradores de masacres, desapariciones, arrasamiento de pueblos enteros, asesinatos, torturas y encarcelamientos clandestinos – civiles de cuerpos policiacos diversos y militares – nunca fueron llevados a juicio. |

|

|

The Mexico Solidarity Project brings together activists from various socialist and left organizations and individuals committed to worker and global justice who see the 2018 election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as president of México as a watershed moment. AMLO and his progressive Morena party aim to end generations of corruption, impoverishment, and subservience to US interests. Our Project supports not just Morena, but all Mexicans struggling for basic rights, and opposes US efforts to undermine organizing and México’s national sovereignty.

Editorial committee: Meizhu Lui, Bruce Hobson, Bill Gallegos, Sam Pizzigati, Courtney Childs, Victoria Hamlin, Agatha Hinman, Steven Hollis. To give feedback or get involved yourself, please email us! |

|

|

|

Web page and application support for the México Solidarity Project from NOVA Web Development, a democratically run, worker-owned and operated cooperative focused on developing free software tools for progressive organizations. |