|

|

|

|

The weekly newsletter of the México Solidarity Project |

|

|

|

Online at mexicosolidarityproject.org |

|

January 11, 2023/ This week's issue/ Meizhu Lui, for the editorial team |

|

|

“I’m a girl. I want to live without fear.” Foto: Toya Sarno Jordan/Reuters |

|

Imagine If You Can: A Life without Fear |

|

As have countless others, I’ve lived with the fear of violence, a fear based on a specific personal situation — in my case, the abuse and stalking committed by an ex-boyfriend. We all face a more generalized fear as well. We wonder if just going to the supermarket or a school might put us in the crosshairs of a gun.

In the United States, many of us also share a fear of government violence, a fear that might come from driving while black or crossing the border while brown. In México, fear of government-complicit violence has run, over recent decades, at an even higher level, both in terms of the numbers of victims and the high ranks of the government officials involved.

When did “disappear” become a transitive verb? Men, women, and children in México do not just drop out of sight. They find themselves “forcibly disappeared” as state actors pull the strings. Mariano Machain, our interviewee this week, knows this crime scene. He works at Serapaz, a group that advocates for laws and law enforcement strong enough to give México the capacity to investigate forced disappearances and bring their perpetrators to justice.

But México also faces those many cases of private violence that we can never afford to ignore. Serapaz seeks to erase the fear these cases evoke by helping people resolve conflicts before they infect a community and turn deadly. An ounce of prevention, as they say in public health, equals a pound of cure.

Bullets that pierce our loved ones leave holes in our own hearts. We're become collateral damage, the walking wounded. What can be more precious than peace? Dare we imagine a girl growing up without fear? A world without fear? Can we make that world so? We can. |

|

|

|

Don’t miss an issue. Subscribe to the weekly México Solidarity Bulletin! |

|

|

|

|

Building Peace, While Defending People's Rights |

|

Mariano Machain coordinates international advocacy for the Mexican nonprofit group Serapaz, a shorthand for Servicios y Asesoría para la Paz/Service and Advice for Peace. Originally from Argentina — and unbearably proud of his soccer team’s latest achievement! — Machain has a background in both international relations and Latin American politics.

How did you become dedicated to bringing about peace in the world and working with Serapaz?

I was born in Argentina, and we suffered a brutal military dictatorship from 1976 to 1983. From my time in high school, I wanted to know how to understand injustice in Argentina — and everywhere else. |

|

|

Serapaz defines itself as a peace-building organization. We work on three levels. We help individual victims organize and defend their rights and help them manage the risks they incur by doing so. At the national level, we advocate for policy change, but Mexican authorities are usually reluctant to take bold action. That’s when we seek international solidarity as additional “persuasion power.”

We also use a variety of tools. Within communities, we discuss methods for conflict resolution to stop abuses before they happen. As guides and protectors, we accompany people as they explore avenues for justice. We work to pass and enact policies, as developed by those who have been affected by violence, to prevent further abuses.

One example: We accompanied El Movimiento por Nuestros Desaparecidos en México to Washington, D.C. in October 2022 when they received a human rights award from the Institute for Policy Studies. We all met with US government officials and asked that the dialogue on human rights between the US and México be resumed — it halted during the Trump years — since the US also indirectly bears responsibility for the violence.

Serapaz has focused on indigenous rights for many years. Has there been an expansion of indigenous rights and protections under Morena?

Bishop Don Samuel Ruiz García founded Serapaz in 1996, after he was asked to serve as a mediator between the Zapatistas and the Mexican government. We continue to work with indigenous peoples and not just in Chiapas.

Unfortunately, with Morena, we have not seen substantial changes. It may be that because we had greater expectations, we also feel greater disappointment. Some of Morena’s new programs have had unintended consequences. Programs aimed at protecting the environment, for example, have actually led to more deforestation. |

|

We placed our biggest hopes in a 2019 constitutional reform proposal guaranteeing the self-determination of indigenous peoples as well as Afro-Mexican communities.

This proposal was developed through an inclusive process. But, for the past four years, the proposal has remained just paper in a drawer. |

|

|

“Here the people direct and the government obeys.” |

|

Forced disappearances have caused a profound human rights crisis. Has there been progress to stop this scourge?

The failed military strategy for fighting crime has seen 106,000 registered as disappeared over the past 16 years. An average of 22 people still disappear every day, almost one person an hour. “Forced disappearances” involve state actors. But in México differentiating between “forced disappearances” and private acts of abduction can be really difficult, given the pervasive collusion between authorities and criminals, coupled with their widespread impunity. |

|

Local collectives of victims’ families have sprung up spontaneously all over México. In 2015, the year the Movement for Our Disappeared in México first came together, we had some 20 of these collectives. Now we have 84, including some collectives in Central America.

The activism of these collectives led to a 2017 national law that codified forced disappearances as a crime. |

|

|

Foto: Serapaz |

|

That new law mandates a special network of institutions, everything from commissions to search for victims and national registries of the disappeared to specialized prosecutors and Citizens Councils. But the law has been minimally implemented, and the pace has been far too slow. Only 36 perpetrators have ever been convicted. We met with US officials in October and asked them to call on the Mexican government to fully implement this law.

One positive: México has accepted the competence of the UN Committee on Enforced Disappearances to investigate individual cases and invited the Committee to visit the country. The Committee has made a report with 86 recommendations, another tool that families of the disappeared can use.

How effective has the Commission set up to investigate the disappearance of 43 students at Ayotzinapa been?

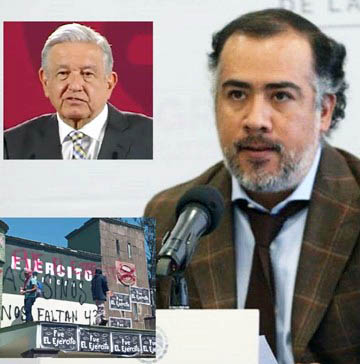

Serapaz has a seat on the Commission, as do five parents and four NGOs, together with various Mexican officials. We felt hopeful when Omar Gomez was appointed as the special prosecutor in 2019. He had been part of a team of international investigators during the previous administration, and they did such good work finding government involvement that they were kicked out of the country and their own lives endangered! |

|

But the government has made serious mistakes in the last few months. In this most critical phase, the time when arrests get made, Gomez resigned and was replaced. The attorney general intervened and blocked the arrest warrants of 21 high-profile officials. And AMLO has been strongly allied to the military. We have a crisis of impunity, and this latest example has eroded trust. That trust must be rebuilt for the Commission to continue its work.

What hopes and fears for peace do you feel?

Even in the present circumstances, amid the lack of progress, we see a lot of social energy and a strong movement. People are not giving up! They continue to demand fairness and justice. They’re on track to achieve results. |

|

|

Ayotzinapa special prosecutor Omar Gomez resigned over differences with the government last September. Foto: Especial, EMEEQUIS. |

|

|

Cross-Border Solidarity in a Pivotal Labor Struggle |

|

The México Solidarity Project, Labor Notes, and DSA labor activists are all currently pressuring VU Manufacturing, an automotive parts maker based near Detroit, to bargain in good faith with the newly elected independent union at its Mexican plant in Piedra Negras. Workers at that plant have just filed, as this excerpted news release below notes, a second complaint against the company under the labor provisions of the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement. This USMCA pact replaced NAFTA in 2020.

Piedras Negras, México — On Thursday, December 29, 2022, members of the Mexican Workers’ League (LSOM) — a democratic Mexican labor union — and the Border Workers’ Committee, a nonprofit worker center, submitted a labor rights petition to U.S. trade authorities against VU Manufacturing for the company’s unlawful attempts to stonewall contract negotiations, intimidate union supporters, and promote a company-friendly minority union within the plant. |

|

|

Julia Quiñones directs the labor rights group supporting workers at the Piedra Negras plant, the |

|

The petition marks the second instance in which VU management’s actions have been subject to review under the USMCA’s Rapid Response Labor Mechanism, potentially making the business the first subject to the RRLM as a repeat offender.

Over the summer, VU management attempted to impose a company-friendly union, the Confederation of Mexican Workers, on the plant after its employees began affiliating with the democratic LSOM union. By June, the company has engaged in a series of anti-LSOM retaliations, prompting members to petition US labor officials, who took up the complaint as the fifth case of its kind under the USMCA. LSOM went on to win a free and fair union election in August by a comfortable margin, leading trade authorities to close the case. |

|

But after the case’s closure, VU management quickly resumed many of the same unlawful practices as before. The company has actively refused to bargain in good faith with the union over a contract, ejected union organizers from the plant, and continued to discriminate in favor of the minority company union. VU has actively facilitated the minority union’s efforts to defame, intimidate, and threaten one of LSOM’s lead organizers. Many of the alleged violations constitute repetitions of the same actions that formed the basis of the original USMCA complaint. |

|

|

“We are fighting for a just collective bargaining agreement to achieve better working conditions and the improved wellbeing of our families,” LSOM’s VU negotiating committee notes. “The vast majority of us workers are single mothers who are trying to get ahead and support their children. We simply desire just wages for the work we perform.”

“We want more stability and a fixed set of benefits, which ought not to depend on the criteria or mood of a given supervisor,” the negotiating committee added. “Having a collective bargaining agreement will benefit the business as much as it will the workers.” |

|

|

Recent news reports and commentaries, from progressive and mainstream media,

Kurt Hackbarth, AMLO’s Four Years in Power Have Been a Success, Jacobin. López Obrador rose to power on the promise of massive redistribution. He has so far nationalized lithium and lifted the minimum wage. But to secure these reforms he’ll need to transform the power structures of the Mexican state and media.

Edmundo Morelos y Vianey Pérez Ángeles, Hijos del Chapo Guzmán: ¿Quién queda al mando del Cártel de Sinaloa tras la detención de Ovidio Guzmán? Todo apunta a Iván Archivaldo, sdpnotocias. Existe una recompensa de 5 millones de dólares para quien dé información que ayude a la captura de los otros hijos de “el Chapo” Guzmán.

Isabel Woodford, Explainer: Why the US-Mexico energy spat is a tough nut to crack, Reuters. The dispute comes after AMLO overhauled the electricity market in the name of national sovereignty, giving the national power utility, the CFE, priority over private energy corporations.

Axel García Ancira Astudillo, Con AMLO, salario mínimo histórico, inflación estable y peso fuerte, Polemón. En 2018 el costo de la tortilla rondaba los 16 pesos, y el salario mínimo era de solo 80 pesos diarios. Por lo que una persona trabajadora podía comprar 5 kilos de tortilla con su salario de un día. Hoy, podemos calcular en 9 kilos y 400 gramos lo que se puede adquirir con el salario mínimo.

Peter Goodman, ‘OK, Mexico, Save Me’: After China, This Is Where Globalization May Lead, New York Times. US companies seeking to limit their exposure to the pitfalls of making goods in China are moving production to México.

Adalberto Santana, 2022, avance progresista en nuestra América, La Jornada. El pasado año tuvo en nuestra América grandes avances y logros en el camino de la ruta progresista de la región.

Mattha Busby, ‘This is another revolution’: could legalization of cannabis transform México’s economy? Guardian. Despite frustrating legislative delays, farmers in México seem keen to start growing a crop that may be more profitable than rice, corn, or sugar.

Operativo para detener a Ovidio Guzmán dejó 29 muertos, 35 heridos y 21 detenidos; descartan bajas civiles, Animal Político. La jornada de bloqueos y balaceras en Culiacán ante la detención de Ovidio Guzmán, presunto narcotraficante del Cártel de Sinaloa e hijo de Joaquín el “Chapo Guzmán”, dejó 29 muertos. De los fallecidos, 10 son militares y 19 del grupo del Cártel de Sinaloa.

Federal government to buy Mexicana De Aviación extinct airline brand for $42 million USD, México Daily Post. The Morena government will use Mexicana to launch a military-run commercial airline.

Gobierno compra la marca Mexicana de Aviación y otros activos por 815 mdp, El Universal. La intención del gobierno federal es crear una aerolínea dirigida por elementos en retiro de la Secretaría de la Defensa Nacional. |

|

|

The Mexico Solidarity Project brings together activists from various socialist and left organizations and individuals committed to worker and global justice who see the 2018 election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as president of México as a watershed moment. AMLO and his progressive Morena party aim to end generations of corruption, impoverishment, and subservience to US interests. Our Project supports not just Morena, but all Mexicans struggling for basic rights, and opposes US efforts to undermine organizing and México’s national sovereignty.

Editorial committee: Meizhu Lui, Bruce Hobson, Bill Gallegos, Sam Pizzigati, Courtney Childs, Victoria Hamlin, Agatha Hinman, Steven Hollis, Daniel McCool, Betty Forrester. To give feedback or get involved yourself, please email us! |

|

|

|

Web page and application support for the México Solidarity Project from NOVA Web Development, a democratically run, worker-owned and operated cooperative focused on developing free software tools for progressive organizations. |