|

|

|

|

The weekly newsletter of the México Solidarity Project |

|

|

|

Online at mexicosolidarityproject.org |

|

February 8, 2023/ This week's issue/ Meizhu Lui, for the editorial team |

|

|

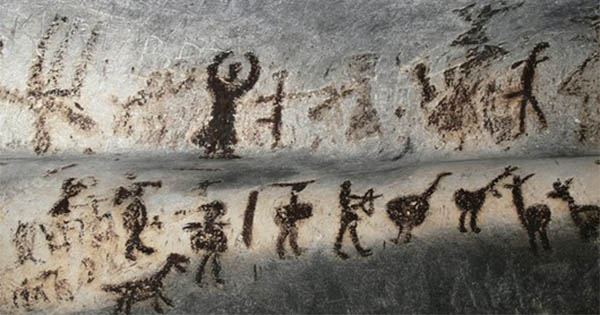

Photo: staticflickr |

|

Seeing Is Believing: The Power of Public Art |

|

It is human to make art. Some 6,000 years ago, our ancestors in Bulgaria created this painting on cave walls, not with acrylics but with bat excrement, quite a long-lasting material as it turns out! These early “graphic novels” offered up dynamic representations of important animals and events in the lives of their painters. The images memorialized and instructed: Those who saw them learned what mattered and how to act.

Public art has been shaping consciousness and behavior ever since, and rulers down through the millennia have recognized and wielded that power. Class societies put the powerful literally on pedestals. Their statues — of Spanish conquistadors and Confederate generals — have dominated public spaces and taught who gets revered and what rates as admirable. The original cave art depicted collective behavior. In subsequent public art, common people became disappeared, except as subservient — or dead — subjects.

But in México, after the Revolution, the people reclaimed public art through Mexican Muralism. The new government hired artists in the 1920s to create a public art that educated even the illiterate about their country’s real history. Workers, peasants, and indigenous people took center stage on the walls of México’s public spaces, as the heroes and heroines who would create a new democratic future.

Murals today remain everywhere in México, and the artworks of muralists like Juana Alicia — who speaks to us in this week’s Voices — have populated México’s calles with people of every race and ethnicity. Revolutionary art such as hers exposes those who would destroy our Earth for a dollar. Art such as hers illustrates resistance and envisions new realities.

What artists like Juana Alicia help us see could not be more critical because seeing — for ourselves — will always be believing. And we act when we believe. |

|

|

|

Don’t miss an issue. Subscribe to the weekly México Solidarity Bulletin! |

|

|

|

|

‘I Feel Thrilled While I’m Painting a Mural’ |

|

Muralist, printmaker, and painter Juana Alicia also teaches — and not just art. She’s taught migrant and bilingual education, as well as community organizing, and sees teaching and parenting as akin to working as an artist. No wonder that she’s done some of her murals in collaboration with students and community, in both the Bay Area as well as cities in México. Her relocation to Mérida means that broader circles of Mexican students — and walls — will be benefiting from her powerful creative presence. |

|

|

Photo by Victoria Alvarado |

|

You came of age in the exhilarating atmosphere of Detroit in the 1970s, a center for revolutionary black workers and the hub of a musical explosion. How did that shape your politics?

I’m originally from Texas, with Tejano/Jewish ancestry. Work at Chrysler settled my migrant family in Detroit in the 1950s. Yes, I took part in civil rights/Black Panther/antiwar actions, and I grew up listening to The Last Poets, Amiri Baraka, Stevie Wonder, Aretha Franklin, and Marvin Gaye: dancing in the streets and feeling the world on the cusp of a revolution!

From Detroit to México! How did that story unfold?

As a teenager, I made posters in solidarity with the United Farm Workers grape strike and boycott and found myself swept up by the Chicanx Movement. In 1972 I met Cesar Chavez at a rally, and he recruited me to work with the UFW in Salinas. I spent several years working in the strawberry and lettuce fields, where I learned from and bonded with my Mexican coworkers.

During that same period, my sister went to college at UNAM, and I began to visit México. I fell in love: the sinking marble museums, the smell of the panaderías, the Zócalo echoing with the voices of millennia and the smell of diesel in the streets of La CDMX. Later, my husband, Tirso Araiza, told me when we met that he intended to live in Mérida, the city of his birth. And we did it! I’m becoming a Mexican citizen. I want to participate in the vibrant cultural life of Mérida, the Yucatán and the country, and contribute artistically to this amazing place.

Have murals become your preferred art form?

My work evolved from the streets of San Francisco’s Mission District, whose mural renaissance has been legendary. I work in many forms, but I consider the mural my favorite. I love the theatricality, the social interaction in a public place, the monumentality, the interface with the environment. I feel thrilled while I’m painting a mural. |

|

Murals make the images accessible to a wide public: to the folks in the streets, at demonstrations or just going about their lives, struggling, loving, suffering, rejoicing. |

|

|

You’ll be walking down the street, and pow! A building becomes a song, a film on walls, an alternative vision to the commercialism bombarding us from billboards to our telephones. The wall opens a door to new possibilities. |

|

Do you intend your works to serve a political/social purpose?

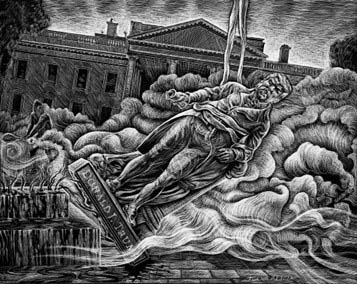

I see some of my murals as wake-up calls, shockers, like The Spill mural in central Berkeley. Others celebrate the power of women, of history, of hope. I visualize a better world as well as project a resounding critique of the systems that destroy us, with graphic art a tool for organizing.

Thanks to allies in the US, some of my images have been enlarged to monumental size and plastered on the streets in several Bay Area locations. The "Get Out! ¡Fuera!” image of the Trump statue falling has become such a piece. The role of this kind of art in urban environments: to humanize public spaces. |

|

|

GET OUT!•¡FUERA! Drawing on scratchboard, Juana Alicia ©2020 |

|

What do you see as an artist’s task in these times?

As Nina Simone once said: “I choose to reflect the times and situations in which I find myself. That to me is my duty.” And at this crucial time in our lives, with everything so desperate, how can you be an artist and not reflect the times? As artists, we can remove structures of oppression from our collective imagination and replace them with visions that celebrate our autonomy and power. |

|

|

Cenotes, Mural at Escuela Superior de Artes de Yucatán (ESAY), collaboration with students, 2007 |

|

|

Paco Taibo’s Republic of Readers |

|

In November 2018, the newly elected President Andres Manuel López Obrador appointed Paco Ignacio Taibo II to lead the storied national Mexican publishing house, El Fondo de Cultura Económica, an appointment tantamount to becoming culture minister. The down-to-earth, humorous, and profane Taibo has been one of México’s most beloved writers — and a courageous critic of Mexican institutions. Highly recommended: the Netflix series based on his detective novel, Belascoarán, PI, that debuted last fall. We’ve excerpted the passage below from a 2019 Marc Cooper profile of Taibo for The Nation. |

|

|

López Obrador’s decision to appoint Taibo matters more in the political sense than you might think. Writers, journalists, and books play a significantly different role in Mexican society than they do north of the border. Authors are a source of national pride: They’re nearly as likely to appear on a talk show as a new pop-star singer…

A Mexican trade paperback can cost $25 or more (in US currency), and many workers make only $8 to $12 a day. “This is why our new fighting slogan is Una República de Lectores,” Taibo says — a republic of readers.

Taibo’s literary plan de choque called for over 70 literary events, fairs, and exhibitions nationwide held in three months. He has ordered the rehabilitation of a small fleet of book buses that his predecessors left to rot, and he’s already using them to visit some of the more remote sections of the country, including in the epicenter of narco activity. Taibo has already launched his first series, “Vientos del Pueblo,” a 400,000-copy press run of eight books priced at $2 or less, including authors ranging from Ariel Dorfman to Michel Foucault…

“I’ve been to hundreds of book festivals, fairs, and exhibitions. I love them,” Taibo says. “When you go to a book festival in the US or Germany, they are beautiful — it’s a moment of pleasure. But in México, when you have a book fair, people come because they are hungry to read, because it is the only place they can afford a book or buy a book. For many of those who come, it is a revelatory moment — they can’t believe you are talking to authors as if they are friends.” |

|

|

Recent news reports and commentaries, from progressive and mainstream media,

Tony Burke, Workers’ representation in México, Evening Star. A close-up look at the pivotal secret sauce in the USMCA Labor Chapter.

Ricardo Ravelo, Caso García Luna: ¿Y el dinero? sin embargo. García Luna es juzgado actualmente en EU por presuntamente tener nexos con el narcotráfico durante su etapa como Secretario de Seguridad mexicano.

Mary Webber, Andrés Manuel López Obrador Says Mexico Wants the $700 Million Corruption Money from Ex-security Chief Genaro Garcia Luna, Latin Post. Luna is currently facing trial in New York.

Manuel Díaz, El sendero de El Marcelo, sdpnoticias. Con el surgimiento del denominado “Colectivo por México” en la escena electoral, aparece una tercera corriente que se prepara para participar en la contienda presidencial de 2024 y todo indica que esta plataforma de MC y Dante Delgado será la que abra las puertas al canciller Marcelo Ebrard.

Mary Beth Sheridan, As fentanyl boomed, DEA removed México director amid misconduct probe, Washington Post. The upheaval in one of the DEA’s most important offices comes as an embarrassing distraction as agents tried to work with Mexico’s corruption-ridden security agencies to deter drug trafficking.

Confirman espionaje con Pegasus a miembro del Poder Judicial Federal, Aristegui. El Secretario Técnico de Combate a la Tortura del Instituto Federal de la Defensoría Pública presentó su renuncia al cargo tras denunciar que fue víctima de espionaje con Pegasus y acusar que existe influencia de “poderes ajenos” a la institución.

Kendal Blust, México’s president says he will retire from political life at the end of his term, Fronteras. AMLO says he will spend his time on a ranch in southern México writing books and will avoid spending time with politicians, attending events, or accepting any kind of advisory position.

Jorge A. Pérez Alfonso, Tribunal rechaza reclasificar delito a Vera Carrizal, agresor de saxofonista en Oaxaca, La Jornada. El magistrado de la sexta sala del Tribunal Superior de Justicia del Estado rechazó ayer la solicitud que hizo el ex diputado priísta Juan Antonio Vera Carrizal, sobre la reconfiguración del delito que se le imputa, es decir, de tentativa de feminicidio a lesiones.

Teresa de Miguel, Worries abound that México’s Maya Train will destroy jungle, Associated Press. The Maya Train is intended to drive economic development to some of the country’s poorest areas, in part by bringing up to three million tourists each year.

Dalila Sarabia, “La disculpa pública no repara el daño que hemos sufrido”: familias de víctimas del Rébsamen exigen justicia y no repetición, Animal Politic. En el acto de disculpa pública y presentación de un memorial por las 26 personas fallecidas en el #19S de 2017, familias de las víctimas demandaron que tragedias así no se repitan. |

|

|

The Mexico Solidarity Project brings together activists from various socialist and left organizations and individuals committed to worker and global justice who see the 2018 election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as president of México as a watershed moment. AMLO and his progressive Morena party aim to end generations of corruption, impoverishment, and subservience to US interests. Our Project supports not just Morena, but all Mexicans struggling for basic rights, and opposes US efforts to undermine organizing and México’s national sovereignty.

Editorial committee: Meizhu Lui, Bruce Hobson, Bill Gallegos, Sam Pizzigati, Courtney Childs, Victoria Hamlin, Agatha Hinman, Steven Hollis, Daniel McCool, Betty Forrester. To give feedback or get involved yourself, please email us! |

|

|

|

Web page and application support for the México Solidarity Project from NOVA Web Development, a democratically run, worker-owned and operated cooperative focused on developing free software tools for progressive organizations. |