|

|

|

|

The weekly newsletter of the México Solidarity Project |

|

|

|

Online at mexicosolidarityproject.org |

|

February 15, 2023/ This week's issue/ Meizhu Lui, for the editorial team |

|

|

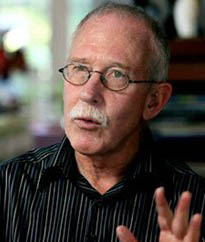

Photo: David Bacon |

|

Removing the Chains Binding Migrant Workers |

|

“We don't want our chains made more comfortable, we want our chains removed,” South African Bishop Desmond Tutu once declared during the struggle against apartheid. “You don’t reform an oppressive state, you destroy it.”

Mexican farmworkers in the United States could well say the same thing about the H2-A temporary visa program for agricultural workers. These visas act as a chain that secures them ever so tightly to a single employer’s control, as the photojournalist David Bacon vividly describes in our interview this week.

Under the H-2A, employers don’t legally “own” their workers. They can’t sell them. The workers more resemble a product ordered on Amazon that customers can return. H2-A workers who become troublesome to their employers render themselves “returnable.” Their employers can replace them with more servile workers at no cost.

We first interviewed David Bacon on the H2-A program’s outrages back in 2021. Later this month, at the February 23-24 binational Global Trade Watch Peace Summit in México City, high on the agenda will be the core question the H2-A program’s existence raises: What can we do to allow people to move across borders as freely as capital?

The US Department of Labor last year issued some new rules — on worker safety and more — that make the chains on farmworkers more comfortable. But we need to do much more. We need to get the chains on farmworkers removed. Nothing less would be justice. |

|

|

|

Don’t miss an issue. Subscribe to the weekly México Solidarity Bulletin! |

|

|

|

|

H2-A ‘Guestworkers’: No Way to Treat a Guest |

|

The work of the acclaimed photojournalist David Bacon offers a window into the daily lives of immigrant workers. Among his books: More than a Wall/Más Que un Muro and The Children of NAFTA: Labor Wars on the US/Mexico Border. In his 2021 report on the US Department of Labor’s H2-A temporary visa program, Bacon documented the reasons why H2-A needs full abolition, not a mere fix. In 2022, temporary farmworkers gained some new protections under the H2-A program. Your take on reforming the H2-A immigration policy? |

|

|

We’ve always had a basic division among those who want to improve the situation of migrant farmworkers. I’m in the camp of those who want radical change. Others want to work within what they imagine can be politically possible.

The H2-A program resembles the old Bracero program, a system notorious for its maltreatment of farmworkers. Organizing by activists in the Chicano and immigrant civil rights movement — like Bert Corona, Ernesto Galarza, and Cesar Chavez — ended the Bracero program in 1965. But in 1986 the notion of a “guestworker” program — a cruel joke for a name — would revive with the creation of the H2-A visa. The new federal Immigration Reform and Control Act also included sanctions against employers using illegal workers. |

|

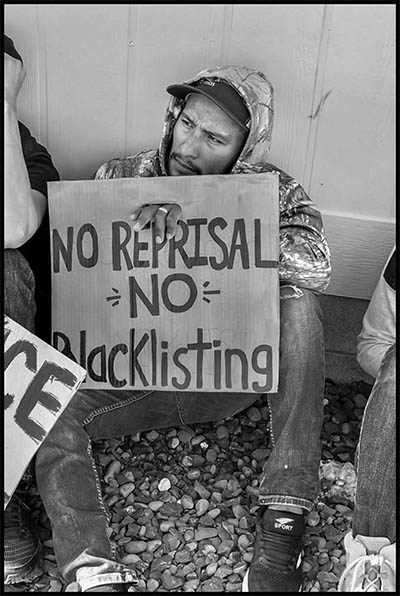

The response to this new H2-A program would illustrate the nation’s political division. Radicals opposed the entire H2-A program and especially its “employer sanctions.” These sanctions made it appear that employers would be punished for hiring undocumented workers. But the sanctions actually operated as a tool to punish workers. Under H2-A, employers could fire workers who organized or went on strike by suddenly “discovering” their own workers' undocumented status. The workers that employers bring into the US via the H-2A program labor at their complete mercy. These workers can work only for the employer that recruits them. If they complain, they're fired, lose their visa, and get deported back to México where they're blacklisted so they can't return in future seasons. The net result: Both undocumented and H2-A workers get deprived of their basic rights. |

|

|

Some people claim H2-A deserves credit for giving farmworkers legal status. But the H2-A visa doesn’t provide real legal status like a permanent residence visa or "green card." It’s only short term, and workers who have H2-A status labor subject to the conditions the boss imposes. How does H2-A affect undocumented farm workers already working? In 1992, the US issued only 10,000 H2-A visas. Last year, growers were certified to bring in 370,000 H-2A workers, a number that has doubled in just five years and tripled in just eight. At the same time, deportations of migrants — almost all workers — have jumped enormously, from 21,046 under Ronald Reagan to 383,307 under Barack Obama. We see a clear correlation between H2-A and deportations. |

|

How has the H2-A program affected the US small and family farms allegedly so dear to the nation’s heart? Farms getting H2-A workers have to provide housing, and even lousy housing costs money to put up. Small farms can’t afford that. The largest growers do have the capital. Their access to H2-A is leading to even more corporate concentration of agriculture. The National Corn Growers Association alone uses 10,000 migrant workers under this program. |

|

|

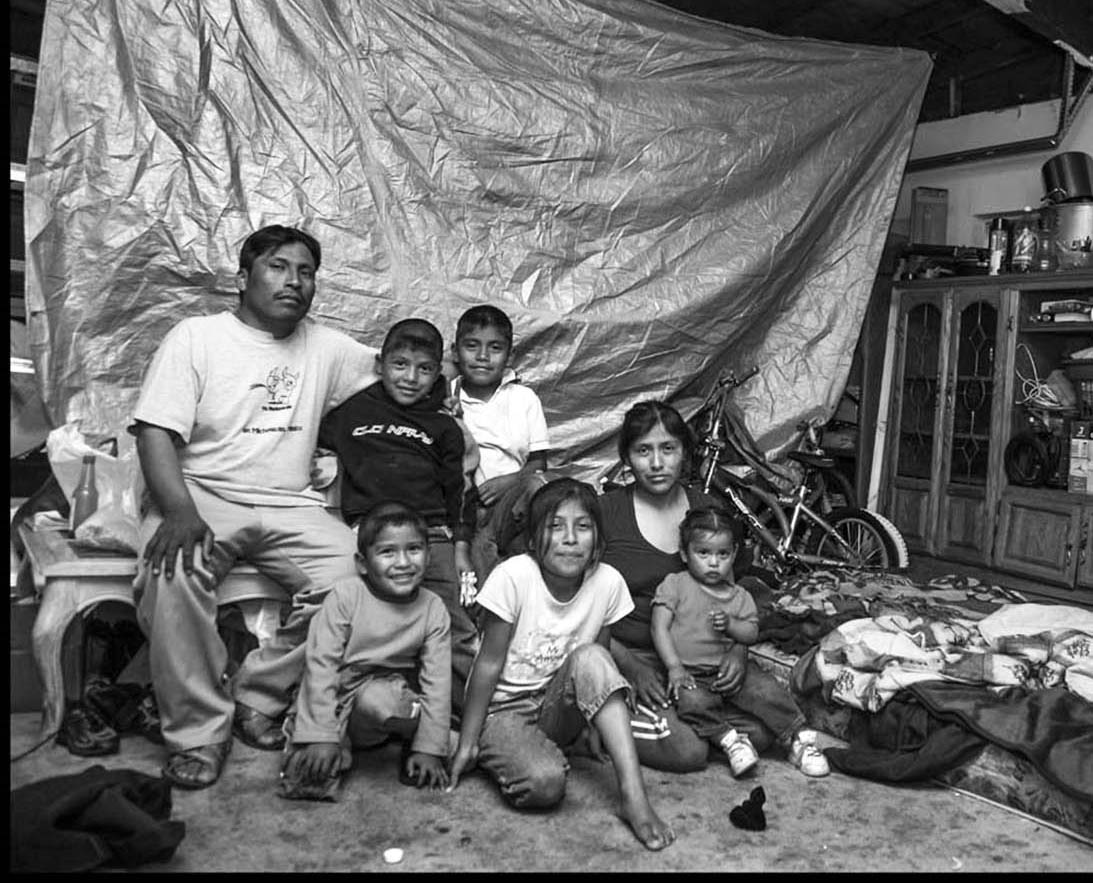

Farms getting H2-A workers have to provide housing, and even lousy housing costs money to put up. Small farms can’t afford that. The largest growers do have the capital. Their access to H2-A is leading to even more corporate concentration of agriculture. The National Corn Growers Association alone uses 10,000 migrant workers under this program. Private recruiting for agricultural workers in México has become a lucrative industry. Would it be better to have the governments handle the recruiting? The Mexican and US governments administered the Bracero program, and corruption — bribe-taking and other abuses — thrived. The private labor contractors have been even worse. They’re also blacklisting activists. The Farm Labor Organizing Committee did open an office in México to monitor corruption. The staff person sent to do that work was tortured and killed for threatening the private contactors’ enormous profits. But involving the governments isn’t going to fix this. Any system based on labor recruitment for growers will be inherently abusive. What does México want? México has argued that getting into the US with an H2-A visa will always be safer than crossing the desert. Neoliberal Mexican politicians have promoted H2-A visas, calling them a route to jobs in the US. And many Mexican families do depend on remittances from a family member working in the US. But AMLO, in his inauguration speech, promised to make México a country Mexicans could be happy living within, rather than one they have to leave in order to survive, and many Mexican communities are demanding the “right to stay home.” Achieving that right will require an economic development that guarantees everything from jobs at home and high farm prices for growing crops for domestic consumption to better health care and education. Economic development like that will always be incompatible with an economy based on remittances. AMLO talks about “failed neoliberal policies” that have food produced for export rather than to feed México’s own people. Similarly, he’s criticized policies that have the Mexican people treated like products for export. But he’s proposed a new government-regulated labor export program that contradicts his promises. Work visas should be abolished and people should be treated as people, not as a commodity called “workers.” What’s the solution? A radical program would encompass, as the Frente Indígena de Organizaciones Binacionales demands, both “the right to migrate” and “the right to stay home.” This would include demilitarizing the border, closing detention centers, and ending immigration raids, as well as stopping trade agreements that force the massive displacement of communities. We should reinforce an immigration system based on family reunification and community stability, while protecting the wages, rights, and health of farmworkers — the alternative advanced by the civil rights movement over half a century ago. |

|

|

|

|

A migrant living on the streets of Ciudad Juárez near the U.S. border. Photo: Cuartoscuro |

|

México Rejects US Return to ‘Remain in México’ Policy |

|

México has rejected a move by the United States to reactivate the “Remain in México” policy that has asylum seekers required to wait inside México while their US claims get processed. The México News Daily earlier this month updated the status of this border situation, and we offer excerpts from that update here.

The Biden administration has pledged to end the “Remain in México” program, which the Trump administration introduced in 2019. In June, the US Supreme Court ruled that Biden had the right to terminate the program. But a federal judge in December ruled in favor of a lawsuit brought by states like Missouri and Texas that argued the Department of Homeland Security had failed to show the policy’s ineffectiveness.

After US authorities notified Mexico of the intention to reinstate the program, México’s Foreign Affairs Ministry issued a statement strongly opposing the plan.

Human rights groups have criticized the “Remain in México” policy — known officially as the Migrant Protection Protocols — for forcing migrants to wait in dangerous border cities that leave them vulnerable to exploitation by criminal groups.

The US, even during the “Remain in México” suspension, has continued to expel many asylum seekers under pandemic-era public health regulations known as Title 42. Like “Remain in Mexico,” Title 42 has been subject to multiple contradictory US legal rulings. A federal judge ordered its termination in November, but the Supreme Court granted a stay in December after several US states argued that a sudden influx of asylum-seekers allowed to stay in the United States to await processing of their claims would overwhelm their services.

If both “Remain in México” and Title 42 are terminated, the US will either have to allow asylum seekers to remain in the country while their claims are processed or make other arrangements to remove them.

After México’s Foreign Affairs Ministry rejected the “Remain in México’s reinstatement, a spokesperson for the US Department of Homeland Security told Reuters that the program “has always been contingent on the government of México’s willingness to accept returns” and that the Biden administration would keep trying to terminate the policy through the courts. |

|

|

Recent news reports and commentaries, from progressive and mainstream media,

David Bacon, What Happened to the Flower Carriers? Dollars & Sense. On the more than a coincidental similarity between Diego Rivera’s image of the man bent beneath a huge bunch of purple flowers and a photograph of a man carrying a similar burden in a California field.

Alejandro Calvillo, ¿Dónde está la oposición? ¿Punto de partida o de retorno? Sin Embargo. “Punto de Partida”, la nueva iniciativa política surgida desde la oposición al gobierno actual presentado por una agrupación llamada Méxicolectivo, carece de un aspecto central en un proyecto que pretende defender y fortalecer la democracia.

Peter Goodman, Why Chinese Companies Are Investing Billions in México, New York Times. Alarmed by shipping chaos and geopolitical fractures, exporters from China are setting up factories in México to preserve their sales to the United States.

Tribunal ordena a Nissan regresar tierras a ejido en Aguascalientes, La Coperacha. El Ejido Peñuelas recibió el fallo favorable del Tribunal Unitario Agrario Distrito 1 en Aguascalientes el cual obliga a la automotriz Nissan a regresar tierras de uso común que la empresa tiene al interior de sus instalaciones desde 2012.

US repeats labor rights review request for Piedras Negras plant, México News Daily. The request follows a petition made in December from two Mexican labor organizations charging that VU Manufacturing continues to deny workers at the plant the right to free association and collective bargaining.

Activistas ambientales apuntan al aguacate mexicano, Proceso. La queja, interpuesta ante un organismo trilateral que forma parte del Tratado entre México, Estados Unidos y Canadá, acusa al gobierno mexicano de no hacer respetar sus propias leyes sobre deforestación, conservación del agua y uso de la tierra.

Jorge Antonio Rocha, México’s super-rich secure their wealth by taking over government policy, Aztec Reports. For every 100 pesos of wealth created between 2019 and 2021, says a new Oxfam report, 21 pesos went to México’s wealthiest 1 percent and just 0.40 pesos to the poorest 50 percent.

Alonso Urrutia y Néstor Jiménez, Al menos 400 funcionarios del INE ganan más que el Presidente: Pablo Gómez, La Jornada. En el Instituto Nacional Electoral hay al menos 400 funcionarios que ganan más que el Presidente de la República, contraviniendo la disposición constitucional que impide expresamente que algún funcionario del Estado mexicano perciba más que el Jefe del Ejecutivo.

AMLO announces that 4 US-financed wind farms will be built in México, Reve. Part of the commitment President López Obrador has negotiated with the United States government to help address the problem of climate change.

Rubén Zermeño, Lucha entre taxistas y Uber deja a pasajeros en medio del conflicto, Indigo. La expansión de las plataformas digitales de transporte a lo largo y ancho del territorio nacional desató una serie de conflictos, pues han puesto en jaque a los taxistas locales, quienes argumentan que no cuentan con piso parejo para operar, por su parte, las empresas dueñas de las aplicaciones aseguran que tienen los permisos para brindar sus servicios. |

|

|

The Mexico Solidarity Project brings together activists from various socialist and left organizations and individuals committed to worker and global justice who see the 2018 election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as president of México as a watershed moment. AMLO and his progressive Morena party aim to end generations of corruption, impoverishment, and subservience to US interests. Our Project supports not just Morena, but all Mexicans struggling for basic rights, and opposes US efforts to undermine organizing and México’s national sovereignty.

Editorial committee: Meizhu Lui, Bruce Hobson, Bill Gallegos, Sam Pizzigati, Courtney Childs, Victoria Hamlin, Agatha Hinman, Steven Hollis, Daniel McCool, Betty Forrester. To give feedback or get involved yourself, please email us! |

|

|

|

Web page and application support for the México Solidarity Project from NOVA Web Development, a democratically run, worker-owned and operated cooperative focused on developing free software tools for progressive organizations. |