|

|

|

|

The weekly newsletter of the México Solidarity Project |

|

|

|

Online at mexicosolidarityproject.org |

|

March 15, 2023/ This week's issue/ Meizhu Lui, for the editorial team |

|

|

Pests vs. Pesticides — and Collateral Damages |

|

Boston, a city where I once lived, hosts some 175 “community gardens,” tiny city- or nonprofit-owned plots where people from every part of the world can plant gardens. People of every nationality, these gardens show, love to put their hands in the dirt, and each nationality has its own horticultural secrets. All this gardening can be quite a sight. Kneeling side by side, people who can’t speak each other’s languages communicate excitedly through their plants, united through their love of the land.

And the land loves them back. Every summer, the carefully tended plots produce tastes of home ranging from beautiful and bountiful tomatoes to Thai basil and bitter melons. Every summer, the planters proudly introduce new flavors to their neighboring plot holders.

What a contrast to the corporate agribusiness all around us! In this week’s interview with researcher Jason Porter, we take a look at how the voracious drive for profit has fueled the growth of enormous factory farms in both the United States and México. In the process, farmworkers have become expendable widgets, their knowledge of the land tossed in the junk heap — and once healthy land no longer rates as arable. The arsenic that factory farms have so widely used turns out to be an element that does not degrade with time.

Yes, pesticides like arsenic do kill unwanted insects. But how much more do they end up costing us in collateral damages? Pesticides kill and endanger snakes and toads, natural species that feed on pests. Pesticides also subject farmworkers, predominantly Mexican and Black, to diseases and even death. Consumers suffer from pesticides as well. They can get sick from food grown on contaminated land. Indigenous cultures see our land as the source of all life, our mother. Pesticide poisons amount to matricide.

Community gardening and the rest of the global environmental justice movement help us understand that we can restore the health of our land — and the health of all living species. All of us make up a global food chain. If we share our traditional knowledge with other “plot holders,” we can unite through love of food and farming. |

|

|

|

Don’t miss an issue. Subscribe to the weekly México Solidarity Bulletin! |

|

|

|

|

Agribusiness: Our Modernity’s Deadly Burden |

|

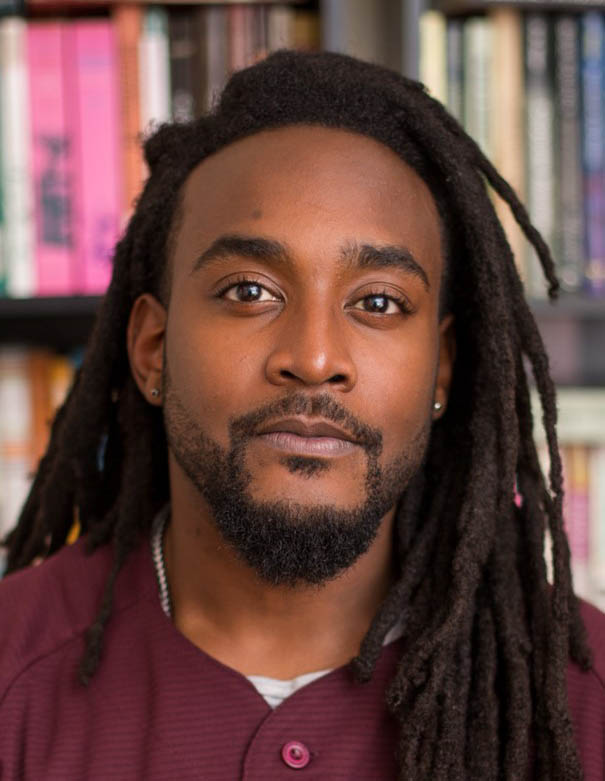

Jayson Maurice Porter, a Voss postdoctoral research associate at Brown University, studies the intersections of the environment and food systems, science and race, throughout México and the Americas. An editorial board member of the North American Congress for Latin America, NACLA, Porter also serves as an environmental specialist for Noria Research's México and Central America Program. An article he co-authored last year with Brian Williams, Cotton, Whiteness, and Other Poisons, appears in the Environmental Humanities journal.

What experience led you to make a connection between Black and Mexican workers? |

|

|

I’ve lived in Arizona and Mississippi for six years each, and traveling in those states I saw plantations being worked by Black, Mexican, and poor farmers. Given the historical sensitivity for place and power — that I gained from my maternal grandparents who fought for justice for Black communities in Philadelphia in the 1960s and 1970s — I began to ask questions in college about how environmental history connects shared histories of race, resistance, and hope. |

|

The history of how US Black and Mexican farm workers came to have a shared story began many years ago. Back in 1910, during the Mexican Revolution, peasants made land a major demand. Did they get what they wanted?

Before the 1910 Revolution, most land had wealthy Mexican and foreign owners, and México had many large haciendas, plantations. Peasant farmers, mostly indigenous and also mestizo and Afro-Mexican, wanted to regain access to and control of land. They wanted haciendas broken up and land owned by foreigners returned to México. |

|

|

Photo: Jim Sugar, Getty Images |

|

The post-Revolution presidents still represented landed interests, so land redistribution in the 1920s at first remained minimal. But land reform did finally take place in the 1930s under President Lázaro Cárdenas, and those years accelerated the ejido system of communal land use. Throughout the 20th century, the government helped establish 29,500 ejidos on 43 percent of Mexico’s arable land.

Landless farmers, in the long and slow process of requesting and receiving ejidos, faced a variety of factors that made the transition to collective land ownership difficult. Pests, especially locusts in southern Mexico in the 1920s, had become a huge issue, with the military the only institution capable of responding. The Mexican government considered this military response necessary because agrarian reform was happening at the same time that rising capitalism and urbanization were creating a growing national demand for food that México’s farms needed to meet. During this period of land reform, the need for efficiency also helped legitimize a state and military presence in rural areas.

Caciquismo, or the rule of local bosses, became another obstacle to land reform. Some ejidos came to be run by “caciques,” local power brokers who ruled the ejido communities to their own advantage. In some cases, U.S. businessmen also became caciques and found ways, after the Revolution, to circumvent the rules against foreign land ownership. In coastal Guerrero, for instance, Afro-Mexican, Afro-Indigenous, and poor mestizo sharecroppers continued to work in the cotton fields and soap factory of Charles A. Miller after the revolution. The days of hacienda-style farming, with its negative impact on poor, racialized farmers, had not ended.

The Revolution destroyed many oppressive aspects of Mexican life, but agribusiness would not be one of them. Larger-scale farms became state-run industries, and capitalist expansion connected many ejidos to the government, urban centers, and global markets. Ejidatarios made some attempts to maintain their sovereignty, but agricultural modernization was developing at their expense. |

|

The market and the desire for profit demanded higher production. Does that explain why pesticides began affecting ejido farms and farmers?

As historian Nicole Mottier writes, the ban on US ownership of land in México did not scare off US companies like Anderson Clayton and Company, or ACCO, a major cotton-trading company. On the contrary, these companies saw opportunity. After all, they didn’t need the land, they just needed the product. |

|

|

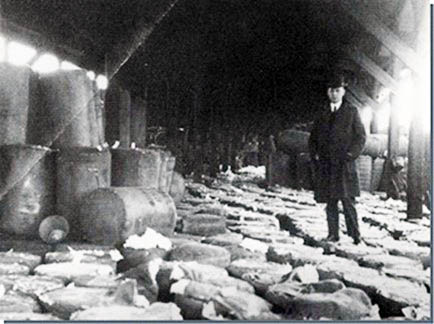

M.D. Anderson in a cotton warehouse. |

|

So firms like ACCO bankrolled the ejido system and granted loans for new ways to maximize production. In the 1920s, they began testing pesticides on cotton in Sinaloa and Sonora.

These chemicals helped render poor farmers expendable, and this toxic pattern only accelerated in the Green Revolution that ran from 1943 through 1960. By the 1980s, nearly 300 farmers a year were dying from acute and chronic pesticide exposure in Sinaloa, a stat that shows dramatically who was bearing the burden of modernity. |

|

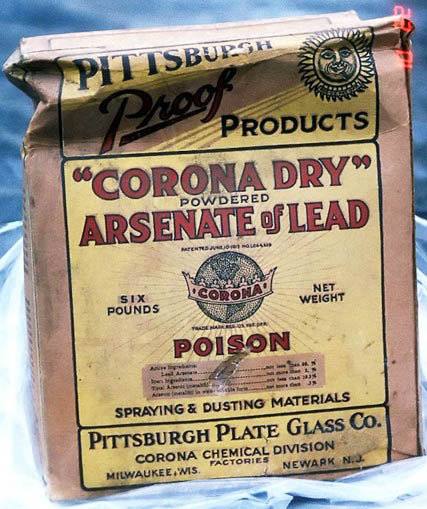

How did arsenic, the first widely used pesticide, move between México and the US?

Arsenic came mostly as a byproduct from the smelting of copper and silver, a large-scale enterprise in late-19th century México. American companies imported arsenic into the US to make glass, paints, and insecticides. US agriculturalists like ACCO began experimenting with arsenic as a pesticide, especially on cotton, and this arsenic became a staple on US cotton plantations in the early 20th century.

The geographer Brian Williams has found that in the 1920s the USDA produced videos to show landholders how to teach Black people to use arsenical insecticides! |

|

|

Photo: Stamford Advocate |

|

By the 1930s, US companies were sending arsenic-based pesticides back to México for use on cotton plantations. Arsenic happens to be toxic to humans as well as insects, but the deadly effects of arsenic, a cumulative poison, took a long time to recognize. In both México and the United States, the Mexican and Black workers who dominated the farm labor sector suffered the most from the deadly effects of arsenic and other pesticides.

What can undo this historical damage — and stop the current damage?

My grandmother Mary Jane used to say that “shoulds” and “ifs” do not exist. I think she meant that we can’t always think about what should be the case or what would be possible if something were the case. We have to work with what we have, and what we have includes examples from history that we can learn from and much more as well, everything from the interconnected environmental networks growing on both sides of the border to the courageous journalists working to keep agricultural-sector dangers in the public eye.

Most importantly, we also have ancestors who worked the land and who can remind us how to care for it. And we need to remember the hard lesson peasants learned in 1910: A revolution may not always be enough. So what can we do to get closer to what we want? We can look to history for answers, to help our revolutionary projects overcome the obstacles that confront us. |

|

|

The San Patricios, Never To Be Forgotten |

|

March 17, St Patrick’s Day, has always been a perfect time to honor the San Patricios.

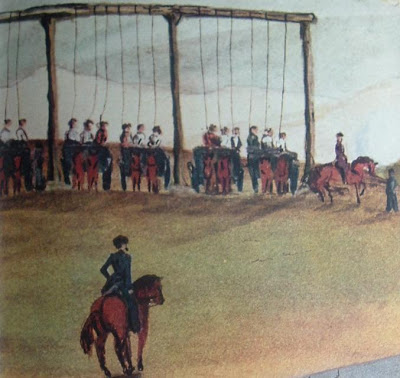

During the trumped-up US war on México in 1846 that expanded the United States “from sea to shining sea,” Irish immigrant soldiers in the US Army found the war so unfair — as did Abraham Lincoln — that they cast off their uniforms and joined the Mexican side. |

|

With México badly outgunned, the war would see 50 San Patricios captured and sentenced to death in 1847. Thirty of these soldiers would be hung in the largest mass execution ever carried out by the US military. That military left the bodies hanging, as a lesson to any who might oppose US intervention.

The San Patricios have become heroes in both México and Ireland. Mexican bagpipers play monthly tributes at the site of the plaque in México City that honors their sacrifice. The Irish band, the Chieftains, teamed up with Mexican musicians and Ry Cooder just over a dozen years ago to commemorate this ultimate act of solidarity. You can watch their tribute online. |

|

|

Samuel Chamberlain: The hanging of the San Patricios |

|

|

Recent news reports and commentaries, from progressive and mainstream media,

México president rebukes calls for US military action against cartels as an 'offense,' Reuters. México, AMLO says, will be informing Mexicans living in the US about the Republican proposal to send troops into México. If GOP lawmakers try to use México for their political purposes, he adds, “we will make a call to not vote for that party.”

Víctor Quintana S., Las cuentas pendientes de la guerra calderonista, La Jornada. El juicio a Genaro García Luna en Estados Unidos no sólo pone en evidencia la colusión de éste con el crimen organizado, sino también cuestiona toda la “guerra contra el narcotráfico” emprendida por Felipe Calderón.

Rafael Bernal, US-México economic ties tested by cross-border tensions, The Hill. The current saber-rattling reminds some of bilateral relations throughout much of the 20th century, when mutual distrust reigned in an asymmetric relationship that former U.S. Ambassador to Mexico Jeffrey Davidow dubbed “the bear and the porcupine.”

Dalila Escobar, AMLO arremete contra republicanos de EU: "A México se le respeta", El Proceso. El mandatario informó que su gobierno comenzará una campaña para quienes viven en Estados Unidos e informar lo que hacemos en México”.

David Bacon, Across The Tracks, The Nation. A community of migrants and unhoused people call the shuttered downtown of this California city — where the polarization of rich and poor remains a constant theme — home.

Ana Lozano, Claudia Sheinbaum, líder en las encuestas. La oposición desesperada, desperdigada y pésima reputación, sdpnoticias. En las todas las encuestas Claudia Sheinbaum sigue a la cabeza; los porcentajes varían según la encuestadora, pero ella sigue en ascenso, situación que ha puesto en jaque a los demás partidos, que no se cansan de buscar al “menos malo”.

Ben Norton, AMLO says México is more democratic than oligarch-run USA, condemns State Dep’t ‘meddling’ against electoral reform, MR Online. In México, López Obrador declared, the people govern.

¿Quieres trabajar en Tesla? Checa sus vacantes en México, Aristegui. Con el anuncio de la llegada de Tesla a Nuevo León, la empresa de Elon Musk publicó diversas vacantes para ese estado.

Peter McKenna, Cuba’s pragmatic foreign policy seeks to strengthen relations with México, SaltWire. The historic positive nature of bilateral relations between México and Cuba have reflected México’s own revolutionary history, Fidel Castro’s exile to Mexico in the mid-1950s, and common fraught relations with the United States.

Elías Camhaji, Cientos de miles de mujeres inundan las calles de México para exigir justicia e igualdad, El Pais. La marea verde y morada del movimiento feminista desborda la política del país, ni el Gobierno ni la oposición logran capitalizar sus demandas. |

|

|

The Mexico Solidarity Project brings together activists from various socialist and left organizations and individuals committed to worker and global justice who see the 2018 election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as president of México as a watershed moment. AMLO and his progressive Morena party aim to end generations of corruption, impoverishment, and subservience to US interests. Our Project supports not just Morena, but all Mexicans struggling for basic rights, and opposes US efforts to undermine organizing and México’s national sovereignty.

Editorial committee: Meizhu Lui, Bruce Hobson, Bill Gallegos, Sam Pizzigati, Courtney Childs, Victoria Hamlin, Agatha Hinman, Steven Hollis, Daniel McCool, Betty Forrester. To give feedback or get involved yourself, please email us! |

|

|

|

Subscribe! Get the México Solidarity Bulletin in your email box every week. |

|

|

|

Web page and application support for the México Solidarity Project from NOVA Web Development, a democratically run, worker-owned and operated cooperative focused on developing free software tools for progressive organizations. |