|

|

|

|

The weekly newsletter of the México Solidarity Project |

|

|

|

Online at mexicosolidarityproject.org |

|

June 21, 2023/ This week's issue/ Meizhu Lui, for the editorial team |

|

|

Photo: Pedro Ambriz |

|

Touch a Child, Touch the Future |

|

As the lone Asian child in a mostly white school system, I saw being Asian as a handicap. I did, that is, until a junior high English teacher gave me a priceless gift that changed me forever. She thought that a story I had written had some wonderful Chinese imagery and asked if my inspiration came from my Chinese background. It didn’t, to be honest. But her question prompted an epiphany in me: I had two cultures to draw from, the other kids only one. I had an advantage, not a handicap!

Teachers can also just as easily tear a young person down. A friend of mine once turned in an assignment so good the teacher actually accused her of plagiarizing. My friend felt devastated. When we’re small, our worlds feel small too, and that only magnifies the impact of our interactions with teachers. We spend as much time with them, as kids, as with our parents. They shape our lives forever.

In our interview today, Pedro Ambriz, an activist teacher born in Michoacan, helps us understand why he sees teaching as a calling, not a mere career. The kids he teaches don’t just learn facts and concepts. They learn a way of being. They participate actively in caring for their school building and grounds. They walk with Pedro in union demonstrations and learn why teachers must sometimes take radical action. Together with parents and teachers, they identify the community problems that most need solving.

The neoliberal mindset so dominant in today’s school policy circles treats raising scores on standardized tests as education’s be-all and end-all. But teachers as dedicated as Pedro Ambriz have a vision of education that goes far beyond test scores, even far beyond just instilling in kids the self-confidence that can help them become personally successful. Teaching, Pedro believes, can and should lay the foundation for social change.

“How much,” Pedro’s students ask in the photo above, “does democracy cost?” The answer that Pedro’s work suggests: Democracy amounts to a priceless gift that good teachers give. |

|

|

|

Don’t miss an issue! Sign up for a free México Solidarity Bulletin subscription. |

|

|

|

|

Education’s Foundation: A Love for Every Child |

|

Pedro Ambriz grew up in the Mexican state of Michoacan and has remained there as a lifelong teacher. He’s also been a long-time local leader of the Coordinadora Nacional de Trabajadores de la Educación, the CNTE, the radical alternative to the old-guard Sindicato Nacional de Trabajadores de la Educación, the SNTE. Teacher activists like Ambriz are fighting for an education system that prioritizes the happiness of every single child they teach. |

|

|

As a child yourself, how did your own education go? Did your school experience make you want to become a teacher?

My family had a lot of trouble affording the books I needed. But my dedicated — and class-conscious — teachers believed that children like me from poor families should get as good an education as they could give.

I did have some bad experiences too. Some of my teachers made fun of me, called me “fat.” That really hurt. But I understood that children had no more important people in their lives than teachers. After high school, I went to a teachers college, and I’ve been a teacher ever since 1995.

Neoliberalism hit the world in the 1980s. México’s President Salinas de Gortari began introducing “reforms” right before you began teaching. What did those “reforms”do?

The changes began under Salinas and got worse under Zedillo and worst of all under Peña-Nieto. From 1988 to 2018 we suffered from the privatization of transportation and health services. Those presidents considered all public services bad.

Peña-Nieto had the slogan “Quality Education.” What a lie! His exam that people had to pass to become a teacher had questions that had nothing to with what and how teachers needed to teach. His expanded education budget went to advertising, to tell the country how wonderful his reforms were working. He should have been making sure every school had electricity and running water or that all children had notebooks and pencils. His reforms created an education of worse quality! |

|

How did teachers respond to the reforms?

We resisted. I’ve been active for a long time in our fighting union, the CNTE. We had demonstrations and strikes in our local areas, particularly in México’s four poorest states, in the south. |

|

|

We also had massive demonstrations in México City to take our grievances directly to the federal government. Teachers went without salaries for months. We had teachers having to sell tostadas on the street. I played the guitar for local events. Our wives and children worked too, cobbling together any money we could.

We teachers have been fighting now for thirty years. For resisting, we were threatened, disappeared, and killed. Resisting become a matter of life and death. In the media, people like Carlos Loret de Mola on Televisa blamed teachers for poverty and misery since, he said, we just refused to work.

Your school didn’t only reject neoliberalism. You created a radical educational model!

I’ve taught at this alternative school for five years now. We named the school after the revolutionary Ricardo Flores Magón, and we’re making a revolution in education! We call our program “Democratic and Cultural Alternatives in Michoacan.” |

|

For starters, we’ve broken the traditional relations of power. We have no director or principal. Every year, parents, students, and teachers select a coordinator. We follow the participatory teaching approaches of the great educational philosopher Paolo Freire. He believed that knowledge grows from the lives students live and from teachers’ life experiences too. We call this “transversal” education. We don’t see knowledge as coming from the top down or from just a set of facts.

In our curriculum we emphasize histories of resistance and revolution against unjust systems. Our analysis rests on dialectical materialism, on the idea that something new comes out of opposing forces, and that new thing becomes the basis for the next cycle of change. We consider history fundamental to our curriculum. From pre-school through high school all children learn the same things, but in ways appropriate to their stage of development. |

|

|

Pre-schoolers, for instance, learn about the lives of revolutionary heroes like Emilio Zapata, Pancho Villa, and Ricardo Magón. At the primary level, we add in the background. What kind of work did people do? What about women? How did people support their leaders? In secondary school, we go deeper. What did the Revolution accomplish?

Our school ranks as the poorest in our region, but the community considers the school to be its own. Our school doors are always open, and teachers and parents work together to tackle drugs and other community problems. |

|

AMLO vowed to end neoliberal education policies. Have things changed?

The educational system still has a lot of the features from Peña-Nieto’s time. We see the system’s teacher evaluations as a capitalist initiative to shame teachers, and we demand that they be ended. We support a different kind of evaluation that would help teachers learn where and how to improve their skills.

Do our schools today have all the supplies they need? No, parents must still dig into their own pockets. Scholarships? Some of my students are orphans or very poor. They get up at 3 a.m. to go to work making bricks or at 5 to make bread or collect trash to recycle before school. They need more than a pencil. |

|

|

At a parade honoring the Mexican Revolution. Pedro Ambriz, his son, and another student advocated for “less ‘Face’ and more book!” and blasted television’s impact. Pedro’s votes-in-a-wastebasket sign illustrated the Mexican Election Commission’s corruption. |

|

We don’t look to the government for support. We count on our union as the structure that best backs us.

How would you describe your teaching philosophy?

First and foremost, kids need love. I treat the students with me as my children. Kids should be happy at school. They shouldn’t be afraid to make mistakes. They need to learn to love themselves. With an education system built around these principles, all students can gain what they need for a good life not just for themselves, but for everyone.

You’re working with the Trinational Coalition to Defend Public Education. How does international solidarity help educators in all three countries?

The Trinational brings teachers together as one family. It helps us become sisters and brothers, to understand we’re not alone, that many teachers like us in and out of our country are fighting for dignity and respect. |

|

We don’t see education as just a book. It’s people joining together for the transformation of society. Education is about sisterhood, about concern for the person in front of you and the person to your side. Education promotes the dignity of every person, at every level of society.

Our 1814 Mexican Constitution says we have the right to be happy. That happiness needs to begin with the children. And teachers, through love, can guarantee this most valuable of rights. |

|

|

Photos: Pedro Ambriz |

|

|

An Extraordinary Artist for ‘Ordinary’ People |

|

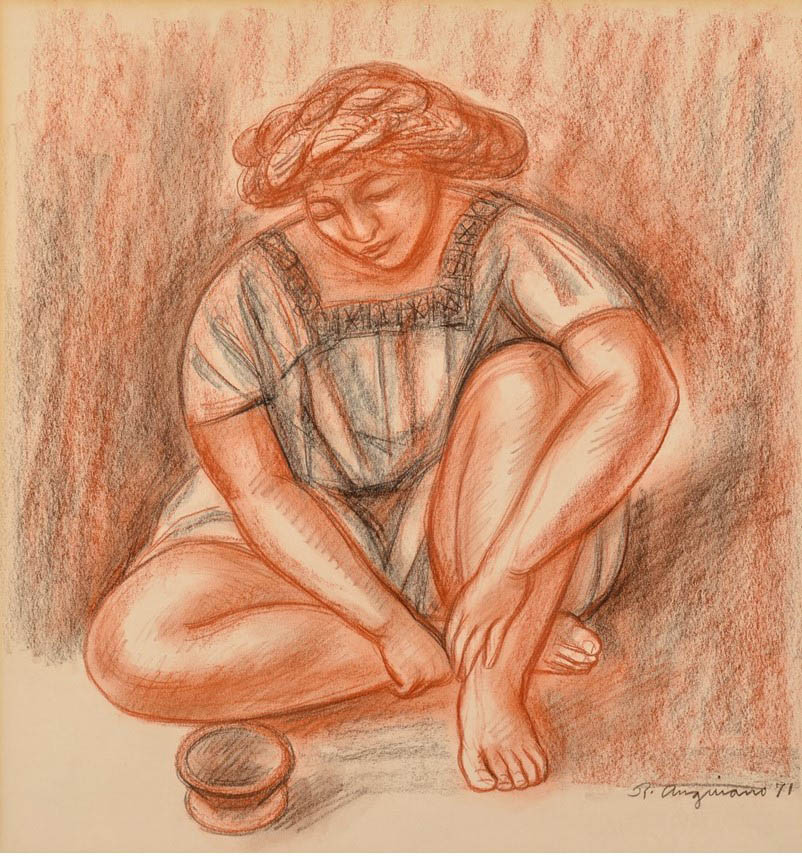

I first took a class with the Mexican artist José Raúl Anguiano Valadez at UNAM, the México City university, back in the sixties and modeled for him as well. I found myself drawn to his depictions of ordinary people living their daily lives and to his so historically Mexican color palette, warm earth tones mixed in with vibrant, strong hues. |

|

I later discovered that I had another connection with Anguiano. In 1937, he had helped found the illustrious Taller de Grafica Popular, the art workshop where my father spent a summer making lithographs in 1941. So, over the years, I would pay close attention to Anguiano’s unfolding work and career. |

|

|

|

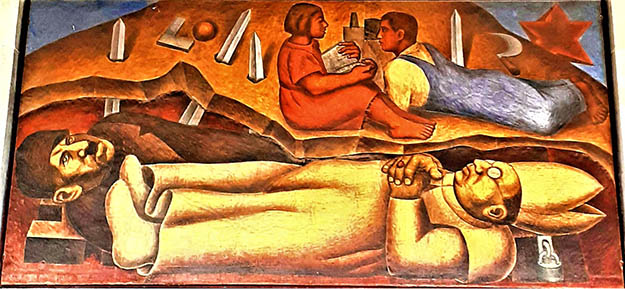

Early on in that career Anguiano would be outspoken in his anti-war views. As time passed, his work would focus more on observing people, often women, and his political views would become a less upfront component of his art. But his feelings for the Mexican people and México’s historical path would always guide his hand. A true man of his people.

Anguiano’s passing in 2006 deeply saddened me. I remember him still as a kindly and caring person and a wonderful draftsman, and I was pleased to realize how important a figure the art world considered him to be. I feel honored to have known him personally. |

|

|

War and the Clergy, enemies of culture. Mural, 1936. |

|

|

Above, La Espina, oil, 1951. Right, a José Raúl Anguiano Valadez self-portrait. |

|

|

|

Above, Woman with Pottery Bowl, charcoal, 1971. Right, Iguana Seller, lithograph, 1983. |

|

|

Activist Vicky Hamlin is a retired tradeswoman, |

|

|

|

Recent news reports and commentaries, from progressive and mainstream media,

Carin Zissis and Chase Harrison, Explainer: How Will México’s Morena Party Pick AMLO’s Potential Successor? AS/COA. An international business press take on the upcoming presidential election process.

Jim Cason y David Brooks, “Rebeldes de Texas”, esperanza para miles de indocumentados, La Jornada. En el corazón de Texas, organizadores socialistas en todas las principales ciudades se reúnen para trazar estrategias, planeando esfuerzos de solidaridad con una potencial huelga nacional de 325 mil trabajadores de transporte, con el fin de exigir justicia a favor de jornaleros indocumentados y armando alianzas con la comunidad.

Dylan Robertson, Left-leaning México seeks closer Canada ties in labor and business amid mining spat, Toronto Star. Canadian Labor Minister Seamus O’Regan calls what México is doing to advance labor rights “incredible” and says he “can’t imagine a society moving faster than they are.”

Diana Delgado y Gerardo Borbolla, De norte a sur, México padece por las altas temperaturas: así se vive la tercera ola de calor, Animal Politic. De Monterrey o Torreón hasta Coatzacoalcos o Mérida, la ola de calor genera diversas afectaciones y obliga a autoridades y ciudadanía a buscar medidas para adaptarse y prevenir riesgos para la salud.

Edwin Ackerman, The AMLO Project, New Left Review. The idiosyncrasies of AMLO’s left-populist presidency have pitted him against both the neoliberal right and the cosmopolitan intelligentsia and neozapatista-adjacent autonomists. AMLO’s overarching project has been to move away from neoliberalism. What can the left learn from his endeavor?

Yulissa Camacho Mora, AMLO imbatible; logra aprobación del 71% de las y los mexicanos, Polemón. A la pregunta de: ¿con cuál partido político se identifica más usted?, la mayoría (48%) dijo que se identifica con Morena. El 18% señalo que son apartidistas y tan solo el 13% manifestó ser partidario del PAN, 9% del PRI.

European Union interested in 2 of AMLO’s green energy megaprojects, Bnamericas. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen says the EU will support México’s plans “to harness a resource you have in abundance: the sun.”

Logran binnizá suspensión de parque industrial del Corredor Transístmico en Puente Madera, Desinformémonos. La comunidad binnizá de Puente Madera logró la suspensión de oficio y plano de la declaratoria del «Polo de Desarrollo para el Bienestar» de San Blas Atempa, Oaxaca, con el que se pretendía destruir las tierras de uso común conocidas como El Pitayal para el Corredor Transístmico. El triunfo llega después de más de dos años y cuatro meses de caminar por justicia, tierra y libertad.

Jorge Antonio Rocha, ‘On the verge of civil war’: Zapatistas march to demand peace in Southeastern México, Aztec Reports. The Zapatista Army of National Liberation earlier this month held a nationwide demonstration to denounce increasing violence at the hands of drug cartels and paramilitary groups in southeastern México.

Elena San José, El polémico exgobernador de Oaxaca Ulises Ruiz se lanza a por la presidencia como independiente, El País. El antiguo político del PRI entra en la competición con un discurso antipartidos y un vídeo en el que acusa al Gobierno de López Obrador de estar aliado con el narco. |

|

|

The Mexico Solidarity Project brings together activists from various socialist and left organizations and individuals committed to worker and global justice who see the 2018 election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as president of México as a watershed moment. AMLO and his progressive Morena party aim to end generations of corruption, impoverishment, and subservience to US interests. Our Project supports not just Morena, but all Mexicans struggling for basic rights, and opposes US efforts to undermine organizing and México’s national sovereignty.

Editorial committee: Meizhu Lui, Bruce Hobson, Bill Gallegos, Sam Pizzigati, Courtney Childs, Victoria Hamlin, Agatha Hinman, Steven Hollis, Daniel McCool, Betty Forrester, Jesús Hermosillo. To give feedback or get involved yourself, please email us! |

|

|

|

Subscribe! Get the México Solidarity Bulletin in your email box every week. |

|

|

|

Web page and application support for the México Solidarity Project from NOVA Web Development, a democratically run, worker-owned and operated cooperative focused on developing free software tools for progressive organizations. |