|

|

|

|

The weekly newsletter of the México Solidarity Project |

|

|

|

Every issue archived online at mexicosolidarityproject.org |

|

July 20, 2022/ This week’s issue/ Meizhu Lui, for the editorial team |

|

|

Just Why Do We Send Our Kids to School? |

|

Should we care deeply about education? We sure should. Public education, the wellspring of democratic societies, can create informed citizens — critical thinkers — who actively participate in decision making about their country’s future. Public education can be a social equalizer, helping those born to disadvantage rise above their circumstances.

And public schools, maybe most importantly of all, can enrich everyone as all children begin to contribute their talents and intellects for the common good.

Education in the United States has never met these lofty goals. At times, for white people, we came somewhat close. In the middle of the 19th century, with settlers moving westward to homestead (on Native American lands!), the federal Morrill Act set up tuition-free colleges on public lands to teach agricultural sciences. Lawmakers wanted to help families learn not just how to survive, but how to contribute to building a thriving nation.

Over time, as internationally recognized educator Mariluz Arriaga explains in our interview this week, education has strayed further and further from its democratic potential. Marx once predicted that as capitalism developed, so would “commodification,” and education has indeed become a commodity. Students now go deep into debt to attend state colleges. Standardized testing today trumps teaching, and we the public have been programmed to believe that we send our kids to school just to get good jobs, not to become good citizens.

The result? We’re reaping the whirlwind. We have too many young people who hate school, who feel like failures, who even imagine that guns may solve their problems.

It’s on all of us to defend public education. Let’s rededicate ourselves to demanding schools where students can start participating in building vibrant, caring societies that endeavor to expand the well-being of us all. |

|

|

|

Don’t miss an issue. Subscribe to our weekly México Solidarity Bulletin! |

|

|

|

|

Uniting to Defend Education as a Social Right |

|

María de la Luz Arriaga Lemus, a classroom teacher before joining the economics faculty at México City’s revered UNAM university, has been a long-time union activist. In 1993, she co-founded the Trinational Coalition in Defense of Public Education with her US and Canadian counterparts. Six years later, she helped launch, on a broader scale, the Social Network for Public Education in the Americas. Her latest effort: the Casa del Obrero Socialista “Antonio Vital.” Arriaga, all told, has spent half a century defending public education as a social right in México and beyond. |

|

|

When did México start guaranteeing education as a fundamental right?

María de la Luz Arriaga Lemus: Education — free, universal, secular — has been a guaranteed social right since the 1917 Constitution after the Mexican Revolution. This right gives young people from any background the possibility of greater life opportunities.

But México, in the years since the 1990s, has adopted the neoliberal model for education from the United States. I’m not talking about the privatization, commercialization, and charter schools you see in the United States. Here in México we don’t have private entities creating single schools. We have a “privatization” of the entire public education system, a turn away from education as a social good to education as a commodity, a tool for individual advancement rather than a system to build capacity to resolve social problems.

The education system, for example, introduced standardized testing. This became — who designs the tests! — a mechanism for reproducing class and racial divisions. The tests put the blame for not going to college on individual students. Their own parents castigate them for not doing well enough on the exams. But the real problem remains that our colleges don’t have enough spaces for students.

The neoliberal “human capital” concept in México treats schools as the factory that produces the workforce that capitalism requires. One example: In 1995, Mexican president Salinas threw out fourth and fifth grade Mexican history textbooks with anything that put the US in a negative light. He even cut out the revolutionary role of Mexico’s “child heroes” during the 1847 US invasion. All this helped make it crystal clear that the education system serves US imperialism and creates a labor force at the service of the market.

You’ve been part of the fight for union democracy. What connection do you see between the right to an education and that democracy?

An important question. I’m convinced that without a democratic union teachers cannot ensure that the right to education goes beyond achieving universal access. The right to education must also be about the transformation of men and women into agents for creating democratic, humanistic, solidarity-based societies. Neoliberalism attacks the autonomy of teachers. But we can’t let them reduce teaching to just a skill-set. Teaching must always be an act of love.

The established SNTE teachers union, long closely tied to the PRI government, has controlled teachers through repressive means. How did the progressive CNTE alternative manage to break away? |

|

The CNTE sees the SNTE — the National Educational Workers Union — as more a mafia than a union.

Workers in México started rising up in the 1970s, with the state in political and economic crisis after the Zapatista revolution. Social discontent was running high. The CNTE started up in 1979, not as an officially recognized union, but a coordinadora of dissident SNTE sections. |

|

|

In 2013, Guerrero state CNTE members, on strike against the neoliberal policies of then-president Peña-Nieto, attacked local political party offices armed with iron rods and rocks. Photo: Lenin Ocampo Torres/European Pressphoto Agency |

|

The CNTE includes all workers in schools, from teachers and administrative personnel to cleaning and cafeteria workers. It exists within the SNTE. Its power comes from support from students and community leaders. The CNTE influences contracts, but doesn’t bargain directly for the most part. Only two sections of the CNTE, in Oaxaca and Chiapas, have official recognition. CNTE also has a strong presence in Michoacan, Guerrero, and Veracruz. But smaller sections exist all over the country.

You cofounded the Trinational Coalition in Defense of Public Education. When did that form and why?

We formed in the 1990s to protest the inclusion of education within NAFTA, a trade agreement — as if education were a product for sale! The Trinational Coalition brings together union and social organizations, including rank-and-file teachers, academics, and students, as well as parents and social organizations. We’re working to define the future of public education in North America as humanist, anti-authoritarian, and emancipatory. We develop common agendas and strategies to challenge our own governments and also support each other. Mexican teachers, for example, demonstrated in front of the US embassy when teachers in Chicago went out on strike.

What can we learn from the Trinational Coalition’s success in getting people in one country to identify with people in other countries and act in concert with each other?

First, solidarity is not charity! Solidarity needs to be based on mutuality. In the Trinational Coalition, we have a place for discussion, friendship, and planning campaigns. We’ve organized ourselves horizontally, with equal say for US, Mexican, and Canadian voices. We look for ways to lend strength to struggles in any of the three countries. In 2005, for instance, the union in British Columbia went on an illegal strike. The government threatened to shut down the union’s internet. Mexican members of the Trinational created a website the British Columbian union could use if necessary.

We see two interconnected premises for achieving real international solidarity. First, continuity. The commitment must be long-term and anchored in practice, not just words. The second, trust. And trust comes from sharing practice. Worker delegations across borders, I believe, can help create the personal connections that advance that sharing.

In critical moments of great uncertainty, such as those we’re experiencing in the world today, we need to ensure that public education strengthens the community — the collective — and promotes societies that inspire our children and young people to create a world that benefits us all. |

|

|

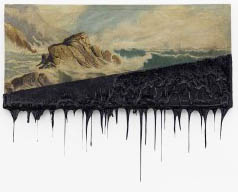

Dark Matter: The Gooey Grandeur of Minerva Cuevas |

|

Minerva Cuevas, a México City-based interdisciplinary installation artist and artist-in-residence at the San Diego Institute of Contemporary Art, has exhibited widely. Her work exposes the underbelly of corporate greed, the dark agenda of the petroleum industry and assorted other toxic capitalist ventures. She helps us imagine ways we can fight back against these giants, using familiar images, humor, and outrage. |

|

|

Her current show at the San Diego Institute, entitled Dark Matter, comes well named. Her “dipped” canvases — peaceful landscapes — are dripping with a gooey, evil-looking petroleum product, a powerful contrast to the sweet country and ocean images. |

|

|

The strangely beautiful antique oil canisters of Minerva Cuevas, all filled with plastic flowers, demonstrate the world we have to look forward to, a world where, if we don’t change course, everything becomes a petroleum product. We become so used to living with poison. |

|

|

The murals Cuevas creates use familiar images, logos, and iconic advertising to “re-brand” the bad guys who are destroying our world. The stunning red-and-black wall in her current San Diego show’s mural depicts critters and plants trying to survive in a petroleum-based environment, with everything painted in red paint and black oil. It makes you cringe, but you can’t stop looking! |

|

|

You can feel the damage being done, the heartless greed that’s stealing our world from us.

A kinder gentler corporate capitalism? I don’t think so, and I doubt Cuevas does either. |

|

|

Activist Vicky Hamlin, a retired tradeswoman, |

|

|

|

Recent news reports and commentaries, from progressive and mainstream media, on life and struggles on both sides of the US-México border |

|

Sabrina Rodriguez, This isn’t the Trump-era of U.S.-Mexico relations. In fact, it’s wildly different, Politico. Mexico’s president has turned the tables on its northern neighbor after years of Trump bluster.

Fabrizio Mejía Madrid, AMLO en inglés, sinembargo. No se necesita ser un genio de las relaciones bilaterales para saber la diferencia entre las visitas de López Obrador y las de sus antecesores.

David Shortell, A Mexican network is sending abortion drugs to American women, CNN. The medications are arriving, say Mexican activists, in a thousand creative ways. . Alejandro Gutiérrez, Adiós a la tregua: la 4T reacciona ante la operación política del exiliado Peña Nieto, Proceso. El anuncio de que la FGR investiga a Enrique Peña Nieto por presunto lavado de dinero ocurrió unas semanas después de que el expresidente se reunió en Madrid con destacadas figuras del PRI mexiquense para acordar cómo enfrentar las elecciones del año próximo en el último bastión del priismo.

Gustavo Maranges, AMLO Meets Biden and Proposes a Change for the Better, Resumen. Obrador’s visit had a ring of difference, a fundamental break from a past of third-world presidents showing up, hat in hands, looking for handouts from the empire’s top administrator.

Rubén Zermeño, La ruta guinda de Morena para ganar en el Edomex, Reporte Indigo. Morena comienza su búsqueda por hacer historia y conquistar el próximo año el máximo bastión priista, pues es una entidad que históricamente ha sido gobernada por el tricolor.

Adry Torres, Filthy rich ‘King of México’ TikToker boasts about 'what his money can do' and creates traffic jam on bridge using his fleet of supercars, Daily Mail. A Mexican deep pocket boasted on social media that he was blocking off the bridge “so you can see again what money can do here in México.”

Arturo Cano, Ganamos contrato de GM por organizarnos y defendernos, La Jornada. Tiene 33 años y 12 de trabajar en ese corporativo; ahora encabeza el Sindicato Nacional Independiente de Trabajadoras y Trabajadores de la Industria Automotriz, con más de 6 mil integrantes, de los que casi un cuarto son mujeres. |

|

|

The México Solidarity Project brings together activists from various socialist and left organizations and individuals committed to worker and global justice who see the 2018 election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as president of México as a watershed moment. AMLO and his progressive Morena party aim to end generations of corruption, impoverishment, and subservience to US interests. Our Project supports not just Morena, but all Mexicans struggling for basic rights, and opposes US efforts to undermine organizing and México’s national sovereignty.

Editorial committee: Meizhu Lui, Bruce Hobson, Bill Gallegos, Sam Pizzigati, Courtney Childs, Victoria Hamlin, Agatha Hinman, Steven Hollis. To give feedback or get involved yourself, please email us! |

|

|

|

Subscribe! Get the México Solidarity Bulletin in your email box every week. |

|

|

|

Web page and application support for the México Solidarity Project from NOVA Web Development, a democratically run, worker-owned and operated cooperative focused on developing free software tools for progressive organizations. |